Why is workplace safety for women such a big ask?

When we talk about Bangladesh's development journey, the role that women have played in propping up the economy is inevitably a part of the conversation. Whether it is as RMG workers, small entrepreneurs or migrant workers, we routinely cite how women's participation in the labour force has not only been beneficial for their economic empowerment, but for the nation as a whole. This is especially true in terms of the RMG industry, where around 60 percent of the workforce are women.

But this proportion has been steadily declining.

In fact, female labour force participation as a whole took a hit during the pandemic, but it is back on the rise again. And, according to data from the International Labour Organization (ILO), it continues to be higher than the South Asian average: in 2021, Bangladesh's female labour force participation rate was 35 percent, whereas India's was 19 percent and Sri Lanka's 31 percent.

However, once you get past the microcredit-induced smiles on the glossy papers of different brochures that focus on the transformational abilities of women's labour – and there's no denying that economic empowerment has changed the fates of hundreds of thousands of our women – there are a lot of questions that can be asked about the state of women's work.

How irregular is it? What is the wage gap? How much of their earnings is under the control of other members of the household? How much longer/harder do they have to work compared to their male counterparts? How do they balance paid employment and the unpaid care work they do at home? How do self-employed women deal with the risks and sudden losses resulting from unprecedented situations such as a pandemic?

And the question that is usually near the top of this list: how safe/secure are women's workplaces? This is important not only because the reality is a grim one, but because this reality is regularly used as an excuse to discourage or directly obstruct women from seeking economic empowerment.

Take, for example, the sexual violence incident that occurred earlier this month, when a woman who provides at-home salon services was called into a house where three men gang-raped her. Of course, this inevitably led to the "What was she doing there?" kind of questions that misogynists love to ask, with the implication being that it is somehow not "decent" to be doing the sort of work that takes you to the privacy of someone's home to provide your service.

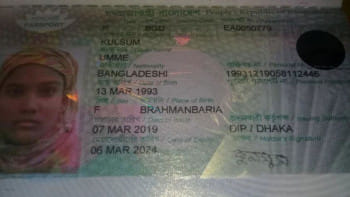

However, the truth is that women are at risk of violence regardless of whether they work in homes, factories, fields or offices. Last year, the Asia Floor Wage Alliance found that RMG workers in six Asian countries, including Bangladesh, faced more violence and harassment during the pandemic, and that Bangladesh was one of the countries where the increased intensity of work was used by managers to get sexual favours. Research suggests that at least 23 percent of female migrant workers have faced physical/sexual abuse abroad, and that female tea workers are much more vulnerable to violence and discrimination than men.

Studies routinely find that women can and do face sexual harassment at workplaces, as well as during commutes to and from work – the fact that every few months we read reports of women facing sexual violence on moving buses is proof of this. Yet what usually happens is, instead of asking why it is so unsafe for women in this country to occupy public spaces, we either advise caution ("If only she had been more careful") or use such crimes as an excuse for why women shouldn't be working in the first place ("Women are safer at home").

The assumption here is that it is up to the individual woman and her alone to ensure her own safety. Not only does she have to support her family financially – by looking after dependents and taking on all household responsibilities – she has to do so within the set boundaries of traditional society, in a way that is "respectable" enough to ensure she is free from violence.

This is especially ironic given that a lot of government and NGO support is in the form of loans that encourage women to become entrepreneurs and set up their own businesses or make their own products, to sell which they inevitably have to travel to markets. ILO data suggests that 66 percent of working women are self-employed. If these women have to depend on someone else to sell their own products (or services), how can we guarantee that the money earned from it won't end up in the hands of the seller (usually a male member of the family) instead?

Quite a few years ago, I interviewed the former state minister for women and children's affairs, who told me that the government was investing in employment that women can pursue from home. It is astonishing that in a country that takes so much pride in the inclusion of its women into the economy, the ministry meant to represent women was taking steps to make that inclusion gendered, instead of doing more to ensure women's safety.

Why should public spaces be so unsafe that women have to take up work that can only be done from the security of home? Why can't women work on factory floors, tea gardens or someone's residence without worrying about being subjected to violence? Do law enforcement, policymakers and employers have no responsibility in ensuring their safety?

We must remember that it is not just traditional gender roles that stand in the way of women. There are times when violence is deliberately used as a tool to discourage women from becoming empowered enough to fend for themselves, or simply from occupying public spaces. Only last month, a female zila parishad member candidate told reporters she had been gang-raped in order to be stopped from contesting elections.

In Bangladesh, women are not only held to impossible standards, they also have to overcome impossible hurdles to establish themselves as equal members of society.

But how are women meant to pursue employment opportunities and achieve economic independence, if the authorities cannot give any assurance that they will be free of violence while doing so?

Shuprova Tasneem is a member of the editorial team at The Daily Star. Her Twitter handle is @shuprovatasneem

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments