Democracy Day 2022: Three decades of backsliding from pledges for democracy

Thirty-two years have gone by since our national leaders made a pledge to make Bangladesh a democracy where the fundamental rights of the people would be protected, and the judiciary's independence and neutrality and the rule of law would be guaranteed. Laws contrary to fundamental rights would be scrapped. Their core pledge was to establish a sovereign parliament elected through a free and fair election.

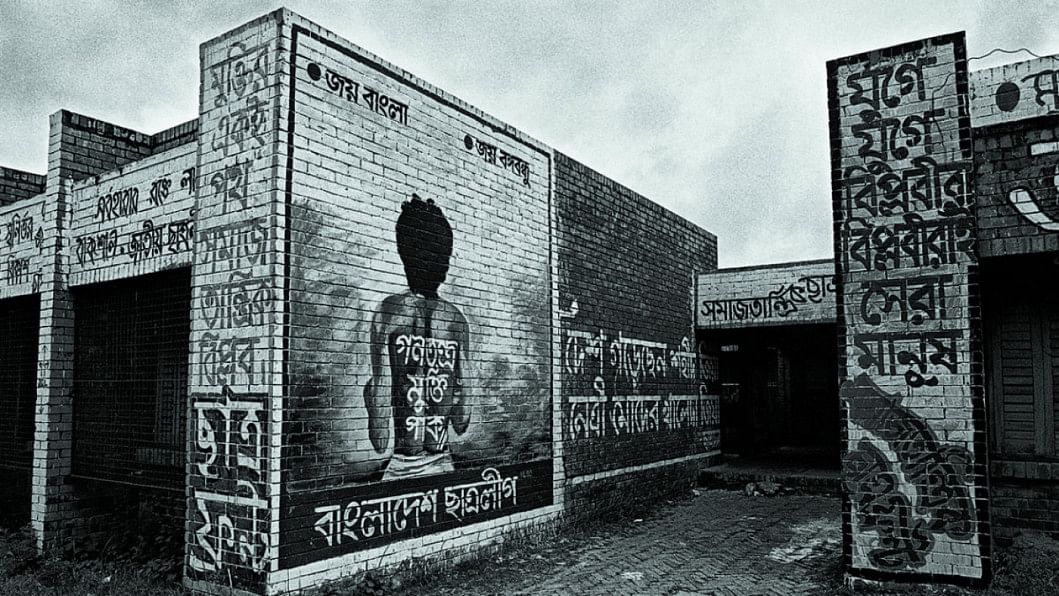

These commitments were made in the Joint Declaration of three alliances on November 19, 1990, demanding the end of military ruler Gen HM Ershad's dictatorial regime and handover of power to a neutral caretaker government. This national accord among all major political parties forced Ershad to hand power over to the nominee of the opposition parties, the then Chief Justice Shahabuddin Ahmed. High hopes and expectations dominated our national psyche for the first few years, but it didn't take long for our politicians to start backsliding on the promises they had made.

The gradual backsliding has now taken us to a state where global think tanks describe us as an elected autocracy. Sweden's Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) is one such institution of global repute that produces the largest global dataset on democracy, with over 30 million data points for 202 countries from 1789 to 2021. V-Dem, in its Democracy Report 2022 titled "Autocratization Changing Nature?", names Bangladesh among 33 nations where substantial autocratisation has happened. Noting the fact that electoral autocracy remains the most common regime type in the world, present in 60 countries, it says, "The level of democracy enjoyed by the average global citizen in 2021 is down to (the) 1989 levels – the last 30 years of democratic advances are now eradicated."

In Bangladesh, too, much of the gains in democratic and civic rights made in the first half of the 90s, following the deposition of the military dictator, have been eradicated. Apart from losing rights and opportunities to vote freely, erosion in the freedoms of expression and assembly have made most people powerless and voiceless. If we go by the latest census, more than half of our population is under 30 years old (26 percent under 14, and 25 percent between 15-29 years), which means they have probably never gotten a chance to vote freely to elect their representatives. As the voting age in Bangladesh is 18, today's 30-year-olds were unable to vote in 2008.

It is probably quite easy for our national leaders to ignore the pledges they made, as half of our population who were not even born then are not aware of the details of the Joint Declaration of 1990 by the three alliances. The scant history or the lone fact that reached them through partisan narrations was that a national movement had brought an end to a military dictatorship, but they are unlikely to know of the pledges of establishing independent judiciary and rule of law, protecting fundamental rights as enshrined in our constitution, and ensuring people's representation through free and fair voting.

This Joint Declaration was not the only thing that was taken out of sight; there was a Code of Conduct, too, which now seems we never had. In the Code of Conduct, the leaders of those alliances pledged, "Our three alliances shall refrain from making personal slander and slandering the patriotism and religion of the other party. The political parties in our alliances will not condone communalism and will collectively resist communal propaganda." They made an unambiguous commitment "to avoid conflict altogether in the electoral process and ensure that the voters can exercise their right to vote freely, and that peace and order is maintained in the polling booths."

Those pledges are nothing extraordinary or unique, and are essential elements in most democracies. But, due to our bitter past, those commitments were seen as a great achievement at that time. Three decades of political history, however, has proven that they were empty promises made by power-hungry politicians and were never meant to be followed through.

Both the Awami League and the BNP have reneged on those promises, but blame each other for betrayal and being anti-democratic. Both have resorted to violence against the opponent, tried to suppress criticism, engaged in vote-rigging, interfered in judicial affairs, and violated fundamental rights – to varying degrees. One thing, however, became clear – that both of these parties were competing to outbid the other. Now, with the removal of the provision for an election-time caretaker government, it has become a one-sided affair, and hence the right to vote has become an opportunity instead of an inalienable constitutional right. The right to assembly for the opposition has now become conditional – with not one or two, but 26 provisos, as laid out by Dhaka Metropolitan Police while granting permission to BNP to hold their rally on December 10.

Last week, I wrote in this newspaper that the government should refrain from seeking transnational repression of its critics abroad. But, a day after, our high commission in Canada posted an announcement on its official letterhead bearing the government insignia, declaring that it would no longer provide consular services to those who were engaged in alleged "anti-state activities and propaganda." There are plenty of tools available to the government to counter any falsehood, but terming anti-government statements and opinions as anti-national is simply wrong and misguided. These are the acts that are bound to make Bangladesh lose its identity as a democracy.

Kamal Ahmed is an independent journalist. His Twitter handle is @ahmedka1

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments