From Grading to De-grading

I recently conducted an oral examination at a college that offers a Master's programme. The meeting started with a plea from colleagues about not failing anyone, otherwise the college would get into trouble. They had incidents where examiners were detained, and cars of teachers were vandalised. The only way to avoid this was to give a bare pass grade in the viva-voce, as they would fail the written examination anyway.

Once the candidates started coming in, I realised that there was no way they could pass, as most of them could not even remember what texts they attempted in the exams they took about a month back. Most of them were irregular students with no interest in pursuing a career related to their MA degree's major. It was a wonder how they made it this far without the required knowledge and skillsets to be in the tertiary system. Their literacy skills were of primary, or at best, secondary level.

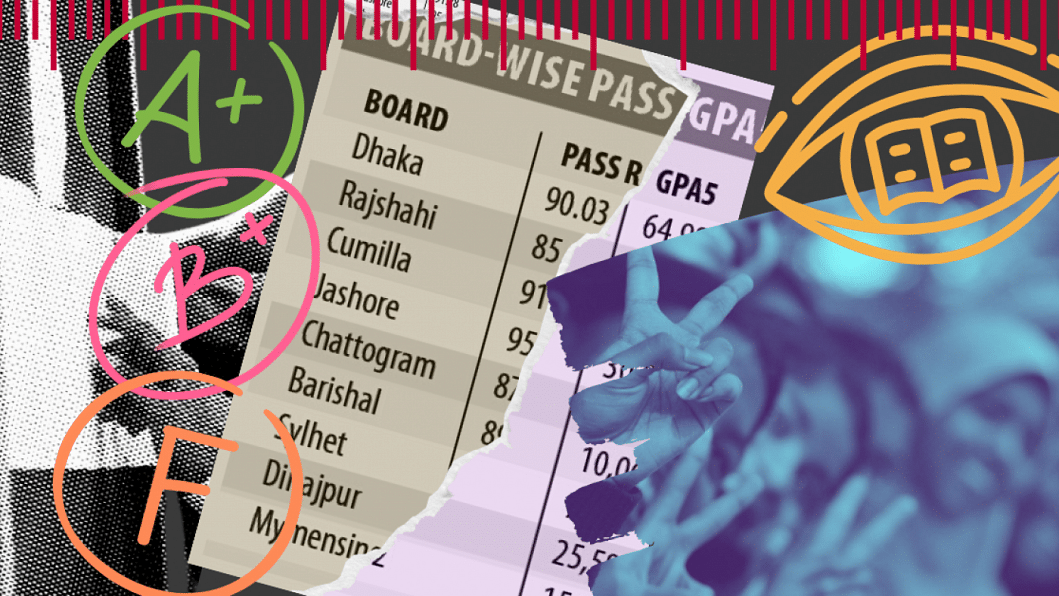

During the exam, I could not help but think about the nearly 90 percent of students who have passed this year's SSC examinations. The switch from online teaching to an offline mode was a massive challenge for them. Their syllabus was shortened. They were given generous options to choose from for subject mapping. In other words, they could further avoid a section of their textbooks. The bar was lowered for them to succeed.

The number of near-perfect golden GPAs has also increased. Still, not everyone is happy. At Chittagong Board, 14,485 students have challenged their grades, asking for a re-check (of which, 7,823 candidates want their English scripts to be reassessed).

The frenzied celebration of the achievements of graduating students, who are now qualified to be in the intermediate waiting room before embarking on their journey of higher education, made me think of their preparedness for the next level. The students I met in the oral examination are products of a system that has allowed them to move on to the next tier without any difficulty.

Of their necessary credentials (i.e., GPA), I have no doubt. They have come through a system that credits grades as everything. But the time has come for us to ask: are grades the real indicator of the aptitudes and acumens of our students? What are the dangers of making grades the yardstick of achievements? How do grades impact the future career trajectory of students?

Whether grades help or hinder student learning is a debate that is as old as the River Buriganga. Some feel grading on a point scale encourages students to chase good marks without meaningful learning. Then again, students know that unless they obtain better grades, their chances of getting into a good college, earning their desired degree, or finding their preferred career will diminish. Such pressure sparks anxiety and stress. We cannot take this lightly, as more than 400 young adults committed suicide in the 14-16 age group last year, according to a mental health service provider survey.

The problem is made worse by the lack of opportunities. Not all colleges and universities have qualified teachers or satisfactory infrastructure. A bad grade means missing out on admission into a good institution. The government has assured that the number of seats at intermediate colleges is higher than the number of candidates. But from a parent's or student's perspective, there are colleges, and there are colleges. Even the fear of a bad grade can cause anxiety and stress, leading to a decline in academic performance and even self-harm.

The mad rush for grades can reduce the creativity of students as well, and suppress their self-esteem. The grade chase makes students adopt cheating and plagiarism, as the public perception of success dictates a logic where learning takes the back seat. Their reliance on memorisation or shortcuts they learn from their teachers at schools or mentors at coaching centres make them ill-equipped for today's career spectrum.

If an institution gets a reward or punishment based on this GPA barometer, they too feel obliged to cater to the grade lust. I won't be surprised if a sociological study of grade inflation finds a connection between social obsession and grade obsession. When news of SSC successes hits national headlines to add to the glory of policymakers, we realise that these grades are beyond the pay grade of educators.

The traditional assessment system made students accountable for their work with a simple frame of reference for their overall standing. The summative grade-point system, in theory, is an international benchmark. These grades give students, and the institutions they apply to, some idea of their overall performances. But the problem arises when there is a mismatch between obtained grades and learning objectives.

Often, we get queries from foreign missions where visa officers are confused over academic transcripts and the knowledge of the subjects they studied. For example, eyebrows are raised if a CSE graduate fails to describe a software. Their confusion is the same as mine.

We need to start making small changes. There are too many stakeholders. The higher number of graduates will make many of the punters – individuals (i.e. students, parents, family members), institutions (i.e. colleges, coaching centres), accessory suppliers (i.e. books), service sectors (i.e. transport, housing, food, dress), happy. A sudden decline and "degradation" will be political suicide for incumbent administrators.

The grade chase is symptomatic of our obsession with numbers. We need a change in the system that holds grades for its quality of evidence. And to ensure quality, we must first change the factors. We need to educate educators. We need to change the mindset of grade glorification. Above all, we need to focus on the learning outcome, not the number of learners.

Dr Shamsad Mortuza is a professor of English at Dhaka University.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments