Infrastructure diplomacy in the context of South Asia and Bangladesh

The greatest bottleneck for a civilisation's development in the modern world is its infrastructure. As populations increase, people's needs and demands increase, the opportunity for industry increases, wages and disposable income increase, and thus you have a cycle of growth.

However, none of this is possible if there aren't good roads, bridges, and railways that people can use to move from home to work and to deliver products from manufacturers to consumers. This is one of the biggest issues holding back development in the Global South.

Now, as international investors step up to fill these infrastructure voids, we see incredible stories of growth and development.

In South Asia alone, millions of people have been lifted out of poverty in the last decade, and a growing middle class has emerged in the region. More growth demands more infrastructure to sustain it. The Asian Development Bank (ADB) produced a research finding in 2009 stating that collective infrastructure investments of USD 8 trillion will be necessary to continue rapid economic development in Asian countries.

Building infrastructure, however, is one of the most expensive projects a nation can partake in. And sometimes, a nation can only get the money to build infrastructure from another nation. Therefore, it makes sense to look at nations from the lens of potential investors and investees.

Traditional investing wisdom dictates that investors should only invest in a nation with steady growth and little to no civil unrest or geopolitical tension. These kinds of investments guarantee the safest returns. However, it should be noted that the nations in the Global South that may require infrastructure the most are the ones that are the least safe to invest in.

It should also be noted that investing nations are never only concerned about monetary returns in the current geopolitical climate. They are also looking for the inevitable soft power gained over investee nations due to the one-sided dependence.

And when it comes to providing risky infrastructure investment in return for soft power, one country stands out above all else.

In Asia, the term "infrastructure diplomacy" is used almost synonymously with China's Belt and Road Initiative. Perhaps the most prominent infrastructure initiative in recent years, the BRI was launched by China's leader Xi Jinping in 2013. It goes without saying that the Initiative is critical to the growth and integration of China's provinces with neighbouring nations, which is in line with China's struggles for hegemony in Asia and in the world. However, with the rising number of nations participating in the BRI, as well as the growth of China's power on regional and global scales, criticism of the strategic tools used for expanding Beijing's economic dominance has steadily intensified. The BRI has received particular accusations of purposefully putting regional nations in so-called debt traps.

Western experts, in particular, point to examples of China's dealings with Sri Lanka and Pakistan as examples of such debt trap policies.

And yet, nations receiving infrastructure support from China consider the investment a great opportunity. For example, opinion polls from the US think tank Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) indicated that the political elites of Southeast Asia favourably appraise China's infrastructure development initiatives, which have delivered tangible benefits to the majority of Southeast Asian countries.

The rise of the BRI and the irresistible offer of development can be hard to deny. As a result, China has managed to provide USD 770 billion of investments to 138 countries worldwide in the last decade. They are leaps and bounds ahead in this game while everyone else is still at the starting line.

But the biggest competition against China's diplomatic strategy in Asia comes in the form of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (QUAD). The military cooperation between America, Australia, India and Japan go far beyond just regional security affairs. Japan is the most active player among the QUAD nations in countering China's infrastructure diplomacy campaign. The vision of the Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP) is one that is shared among all QUAD members, but it is Japan that is targeting enormous amounts of ODA towards Asia in order to provide an alternative to China.

This, of course, is very good news for the region's developing nations. Developing economies dominated by a single foreign investor tend to exhibit distinct indications of neocolonialism. However, investee economies with multiple large investors who have diametrically opposed interests, and are permitted to compete in an open market framework, would likely result in having more equitable infrastructure development.

In the context of Bangladesh, which is set to soon graduate out of its least developed country (LDC) status, we see all the lessons of infrastructure diplomacy in full swing.

Generally, the type of economy, governance and level of democracy in a developing nation play a massive role in determining the kind of infrastructure developments taking place. For example, if a nation relies on natural resource export and is governed as an autocracy, the only infrastructure developments that will take place are from the port to the mines and oil fields. This is, however, not possible in a democratic nation where the government is accountable to the people, and all infrastructure will have to prioritise the common people over the interests of the elite. The situation in Bangladesh, which is identified as a hybrid regime, is, unsurprisingly, somewhere in the middle.

The only true resource Bangladesh has is its people. The people who produce the affordable garments sold around the world, and the migrant workers who send back remittances. Infrastructure development taking place in Bangladesh is targeted to increase the productivity of these people, and as a side effect, somewhat increase their quality of living.

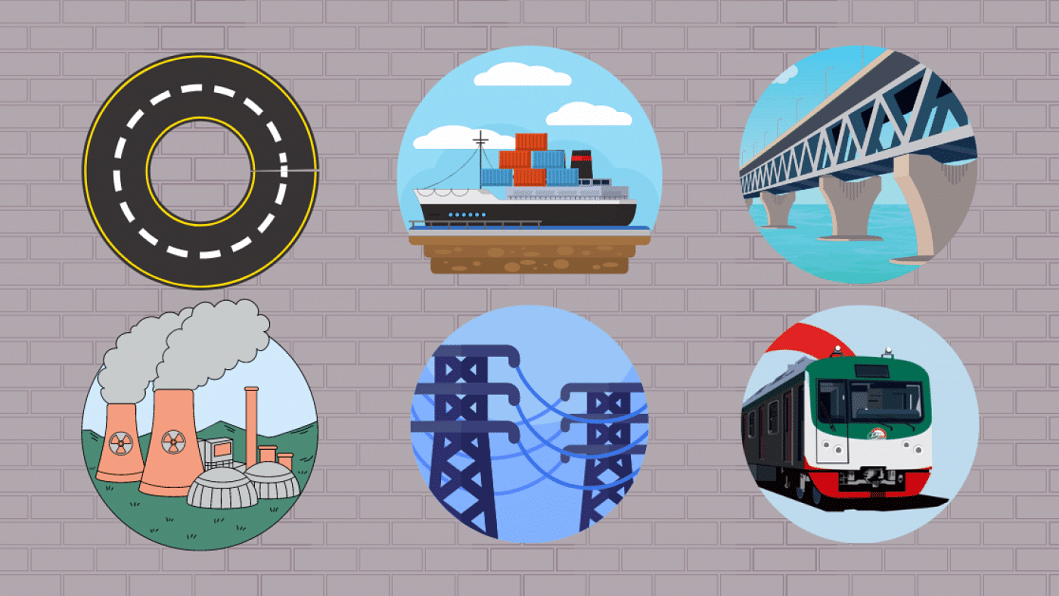

Before the Covid-19 pandemic and the Ukraine-Russia war, Bangladesh gladly took advantage of current great power rivalries to facilitate well-rounded levels of infrastructure development in roads, bridges, railways, airports, energy, and in building climate resilience. However, the recent economic shocks from abroad and rising worldwide inflation, compounded with the current internal civil unrest due to rising anti-government sentiments, are proving quite the stress test to the nation's macroeconomic stability. The main concern now is whether Bangladesh can emerge out of the LDC category without being in crippling debt.

Early warning signs are already in the wind, particularly in terms of Bangladesh's energy bottlenecks.

Though it is true that Bangladesh is nowhere near the dreaded debt trap situation, the nation is already deeply committed to multiple nations. And the true cost of these commitments is yet to be felt. For example, the Rooppur Power Plant will be Bangladesh's first nuclear power plant, with the first unit expected to start operating in 2023. The plant is predicted to eventually provide 15 percent of the country's electricity. Russia is financing up to 90 percent of the project through credit. In addition, Rosatom, the Russian state-owned company running the project, will supply equipment, expendable materials, and training to maintenance crews throughout the plant's operation. Nuclear power plants such as those constructed in Bangladesh, Egypt and Turkey require routine maintenance in order to remain operational. By using Russian reactor technology, these power plants will be reliant upon Russia for upkeep and capital indefinitely.

This dependence is one of the key pillars in Russia's nuclear and energy diplomacy, and it also has tremendous geopolitical implications for developing countries such as Bangladesh. While China and Japan battle over Bangladesh's rails, roads, bridges and ports, with just this one project, Russia may have gained more soft power in Bangladesh than what the Western world is yet to realise.

For a developing country, geopolitics is almost always a losing game. The more the country attempts to modernise and develop, the more dependencies it has to step into. The calculation then becomes a question of damage control.

If investments come with strings attached, perhaps one course of action is to take on as many different strings from as many different puppet masters as possible. True autonomy and sovereignty may be a pipe dream, but at least no one puppet master will ever have full control.

Zillur Rahman is the executive director of the Centre for Governance Studies (CGS) and a television talk show host. His Twitter handle is @zillur

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments