‘Unpredictability has become the new normal’

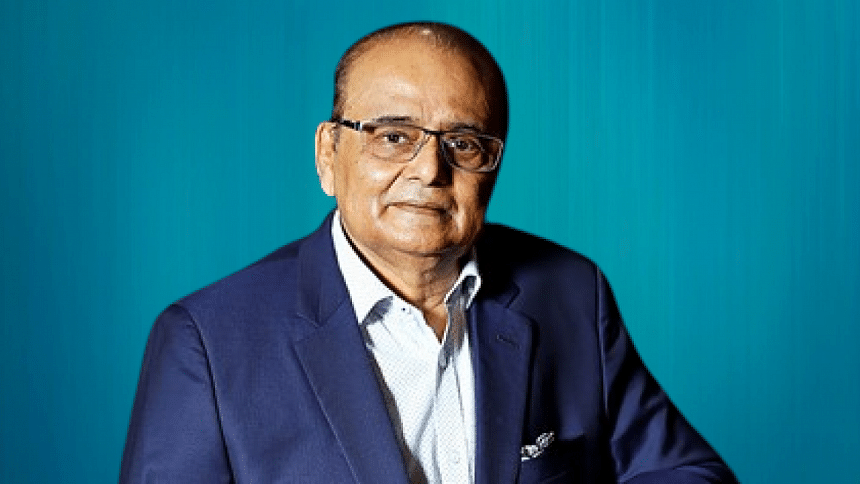

Dr Zaidi Sattar is chairman and chief executive of Policy Research Institute of Bangladesh (PRI). In an interview with Eresh Omar Jamal of The Daily Star, he explains how well Bangladesh has overcome last year's economic challenges, and its economic outlook for 2023.

Bangladesh faced a number of economic challenges last year. How much of that have we been able to overcome?

In 2022, Bangladesh's economy faced an acid test of sustainability, in the company of many developing and developed economies of the world. To put it succinctly, the economy buckled but did not break.

While many developing economies suffered from debt and balance of payments (BOP) crises resulting in debt default, that was not the case for Bangladesh. This was because of nearly three decades of tenaciously maintaining macroeconomic stability – in terms of both internal and external balance – that gave the economy a strong footing to face the economic shocks of 2022. The resilience of the economy was also tested on two earlier occasions, the Global Financial Crisis of 2007-08 and the Covid-19 pandemic of 2020. In both instances, the Bangladesh economy emerged with flying colours.

Indications are that the authorities are keeping an eye on the ball, corrective measures (though not all perfect) are being taken, and results are showing up gradually. The year 2023, therefore, holds promises of resilience and recovery.

Indeed, 2022 presented much more than a troika of economic challenges: inflation, large balance of trade and current account deficit, dwindling foreign exchange (forex) reserves, the dollar crisis, rapid exchange rate depreciation, and so on. Apart from inflation, the rest are part of the same shock – all externally driven. To expect the amelioration of their impacts on the economy in a few short months would be overly optimistic. But evidence suggests the corrective measures adopted are on the right track, with some refinement due going forward.

I would describe the dollar crisis as an excess demand situation for foreign exchange. When 80 percent of imports are destined for the economy's productive sectors, a surge in imports indicates high production activity, as can be seen from the export surge as well. Excess demand for foreign exchange was the result of a massive surge in imports at a time when exports (up 35 percent) were also booming. Remittances were modestly lower than the record inflows of the previous year, but much higher than the average for the past 5-10 years. So, reports about remittance falling are misplaced. The import bill far exceeded receipts from exports and remittances, resulting in excess demand for US dollars. This generated the largest current account deficit of USD 18.7 billion or four percent of GDP. That was the source of the BOP problem, which ran into an overall deficit of USD 5.3 billion.

The other reason for the dwindling forex reserves was the initial effort to maintain the taka-dollar exchange rate at around Tk 86/USD. Emerging markets and developing economies lost as much as USD 200 billion in such attempts to shore up their exchange rates, as the US dollar appreciated about 20 percent in the year. In Bangladesh, with the huge excess demand for forex, this rate was untenable, and the Bangladesh Bank (BB) tried in vain to protect that rate by releasing copious amounts of forex to create adequate supply of USD in the market.

For the past five years, we have argued that BB should allow the exchange rate to move with the market, as it was significantly overvalued. Ultimately, BB relented around June-July 2022, letting the exchange float until it reached about Tk 105/USD by close of October, where it has stayed. Another disturbing feature of this scenario was the introduction of multiple exchange rates – a rate for exports, another for imports, still another for remittances. We have strongly argued for moving away from such an inefficient system, towards a uniform and flexible exchange rate. It seems the BB is gradually moving in this direction.

The exchange market is still not settled, as reflected by the divergence between the rate for remittances and the kerb market rate that continues to incentivise remittance inflows through informal channels (hundi). BB is stepping in to divert remittance inflows into the formal channel through stricter monitoring and opening of more convenient avenues, such as the option of using digital financial services like BKash, Nagad, Rocket, etc. These measures are proving effective, as the monthly official remittance figures of October-December 2022 showed an upward trend.

The exchange rate depreciation of about 20-25 percent since May 2022 is here to stay, but the move toward a stable rate may still be incomplete. The administrative curbs on imports appear to be working, but it is time to relax such controls as they are grossly inefficient. BB should now let the market mechanism play its role as the price of imports are significantly up due to exchange rate depreciation, and that should be sufficient to restrain imports without affecting the productive sectors of the economy. At the same time, exchange rate depreciation and a flexible rate will generate the forces of restoring BOP equilibrium via the market mechanism.

What issues should policymakers be looking at this year to ensure they are not caught off-guard by economic challenges again, like they were in 2022?

The pandemic and Russia-Ukraine war seem to have marked the end of a long period of geoeconomic and geopolitical stability and predictability around the world. Our policymakers were not alone in being caught off-guard, and there are lessons to be learned.

Macroeconomic stability must be made the highest priority. Thankfully, unlike so many other developing economies, Bangladesh did not face any debt distress. Some media reports represented Bangladesh badly, which was ill-deserved; so much so that the IMF spokesperson had to come out and clarify that Bangladesh's request for IMF support was a preemptive measure to stay in the comfort zone with forex reserves. The World Bank-IMF debt sustainability analysis concluded that Bangladesh had "strong debt carrying capacity."

Nevertheless, the strategy of maintaining debt sustainability must be taken as a national imperative. While it is critical for Bangladesh to continue making investment in 21st century infrastructure and human development, it must not be at the cost of risky debt obligations.

The criticality of higher domestic resource mobilisation cannot be overemphasised. Future investible resources must come more from domestic sources, while avoiding any debt overhang situation. Attracting more foreign direct investment into high-cost modern infrastructure is now a greater national imperative.

What is your overall economic outlook for Bangladesh in 2023?

Unpredictability has become the new normal in a world afflicted by the forces of deglobalisation amidst rising geopolitical tensions, as if inward-looking nationalistic and protectionist forces of "reshoring," "friend-shoring" or "strategic autonomy" of the recent past were not enough. The Bangladesh economy will have to steer through some uncharted waters in the areas of geopolitics and geoeconomics. That will require vision and strong negotiating skills.

Which way the war in Europe will play out in the coming months will overwhelmingly determine the prospects of global trade, growth and energy security for 2023.

Bangladesh is now far more integrated with the world economy. What happens in G20 economies is key to Bangladesh's export prospects.

Despite the slowdown in the global economy, the RMG sector in particular is expected to remain buoyant, especially since most top retailers in the EU and US have cited Bangladesh as the "number one" sourcing country over the next 5-10 years after the recent issues in Sino-US trade. We already see a pick-up in apparel exports that is likely to continue.

GDP growth prospects in FY2023 for Bangladesh, according to World Bank, IMF and the Asian Development Bank, are still in the comfortable range of 6-6.5 percent, which will have to be revised downwards in light of import controls and contractionary monetary policies to tame inflation.

Even then, in 2023, I expect inflation to be down to historic levels, the dollar crisis will abate significantly, exchange rate will stabilise at a uniform but flexible rate, and forex reserves will stabilise or even rise modestly.

How soon this will happen depends on how effectively Bangladesh Bank can implement the corrective measures now underway. Of course, such optimism about 2023 is predicated on the assumption that the Russia-Ukraine war does not end up in a grinding stalemate that upends future global growth and energy security.

What should be our target in 2023? Should it be to stabilise our economic fundamentals, focus on growth, or something else?

Thankfully, the two economic drivers of the Bangladesh economy – RMG exports and migrant remittances – are on track to remain robust in the coming year. For RMG, the China factor (redirection of export orders) will, in my view, more than compensate for any slowdown of demand in the EU, which most analysts say is heading towards a recession. As for migrant workers, we have sent 1.1 million workers abroad in 2022 (another record), most of whom will be sending their hard-earned savings back home. The challenge will be to get the inflows into formal channels, which will then help shore up forex reserves.

Maintaining macroeconomic stability should remain the priority. Such stability is what provides the foundation for rapid inclusive growth, which will have to remain the strategic objective for attaining Upper Middle Income Country (UMIC) status by 2031. Rapid growth must proceed, with equitable distribution of its benefits.

Bangladesh's five-year plans and prospective plans have identified export-led growth as the country's development strategy for achieving growth rates of 7-9 percent over the next two decades. For this to happen, the country must embrace trade openness and dismantle burdensome protective tariffs that stifle export competitiveness and impede export diversification, while also imposing heavy costs on hapless Bangladeshi consumers.

HSBC Global projects that Bangladesh is poised to become the ninth largest consumer market in the world by 2030, ahead of the UK. That prospect could be undermined by the high tariff walls persistently protecting the domestic market, unless the economy decides to come out of this stifling tariff regime on the way to reaching UMIC status.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments