Voicing and challenging workplace sexual harassment in Bangladesh

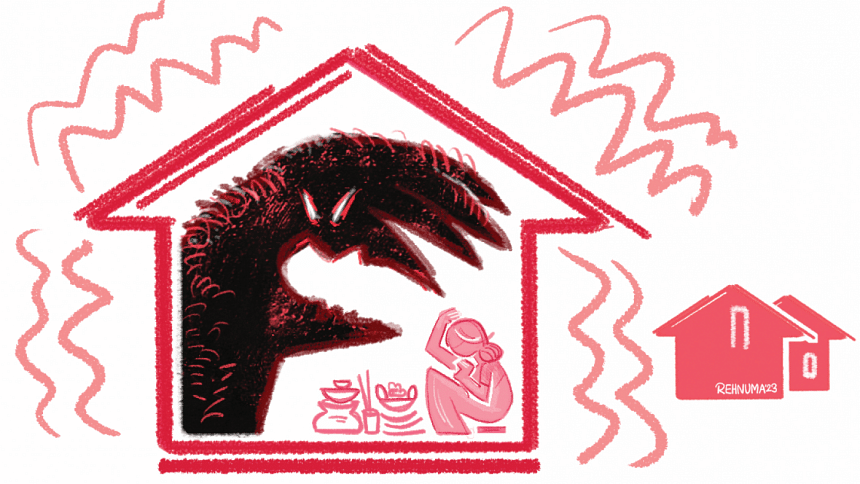

Workplace sexual harassment is common in Bangladesh. It inhibits women from entering the labour market and is also a major reason why they drop out of work. Using case study research with factory workers in agro-processing firms and domestic workers we have seen how language, social and gender norms constrain young women's voice and agency in response to sexual harassment.

Harassments experienced by the domestic workers and agro-processing workers:

Although official statistics show that among the 60.8 million employed, an estimated 5.5 percent have experienced sexual abuse [7.4 percent for urban women (BBS 2018)], the phenomenon is mostly underreported. Workplace sexual harassment refers to a range of inappropriate practices with implicit or explicit sexual undertones regarding women's bodies and self, usually done by men, which happen as the result of power and gender hierarchies.

The Gender and Social Transformation team of the BRAC Insitutue o f Governance and Development in collaboration with the Department of English and Humanities, BRACU and Insitute of Development Studies Sussex, carried out qualitative research with live-out domestic and agro-processing factory workers in and around Dhaka, between 2020 and 2022. These workers reported different forms of harassment at the workplace and on the way to work. Workplace harassment for both types of workers includes a wide range of abuse with varying degrees of severity, ranging from jokes and comments to sexual assault. Domestic workers reported a wider range and greater severity of harassment. Looking or leering or gesturing is the most common form, which all respondents reported to have experienced. The majority of domestic workers had experienced physical abuse at least once and some had experienced incidents of severe physical abuse.

Verbal harassment with sexual overtures debases workers and robs them of self-respect. It is prevalent and can be in the form of compliments, sympathy, assistance, or vulgar remarks. Domestic workers face it mainly from the male members of their female employer's household. For agro-firm workers, verbal harassment from supervisors or superiors was rare but common in public spaces.

Talking about sexual harassment women of both categories of workers commonly used the terms relating to "honour" and "shame". Shame ("lajja" or "shorom") is supposed to be felt by women when they are looked at or commented on, and this was mentioned by many of our interviewees. In the language used, women were therefore taking the blame away form the perpetrator and assuming the responsibility for the various incidents.

The vulnerability of young female workers to sexual harassment is influenced by social and gender hierarchies in the workspace, the conditions for formality or informality, their socio-economic background, and their age. Live-in domestic workers are most at risk of sexual harassment due to their isolated working conditions. On the contrary, the factory floor is less risky for the factory workers as they are surrounded by colleagues. Many agro-processing factories have sex-segregated floors. Supervisors are protective of the factory's reputation and guard the behaviour of all workers. The working conditions of domestic workers are completely informal and they have no formal organisation to protect their rights. Poverty, hierarchy, and informality create a power asymmetry that offers them no protection. In contrast, the factory workers and their supervisors work under semi-formal conditions. While most workers have no contracts, some have complaint mechanisms that offer some recourse for justice. Despite the power asymmetry, factory workers have the strength of numbers which gives them greater courage.

Social gender norms lead to the sexual vulnerability of young female workers. Sexual harassment is normalised for girls in most situations i.e. it is expected to be part of the experience of working life that men will try and take advantage of women and see them as sexual objects. It is assumed that girls have the responsibility of protecting themselves and their reputation. They are to be modest and not attract attention, not be heard, and never take the initiative of speaking to or approaching a man. Male family members are considered "guardians" at home and in public. On the factory premises, the male supervisors assume the role of "guardians" and take action to discipline those men who misbehave with the girls.

The concepts or norms of "honour" and "shame" heavily influence how sexual harassment is seen and acted on, for both types of workers. They describe incidents differently depending on who they are speaking to and masking their language when speaking to employers and authorities. Also in interviews, expressions such as "I don't know anything about it", and "I forgot" were used and many did not want to talk about it.

Everyday Language of Sexual Harassment

The interviews showed a lack of adequate vocabulary regarding sexual harassment at work. Many were not aware of what constitutes sexual harassment. Explicit terms were avoided, and indirect expressions were mainly used to describe incidents of sexual harassment. The use of words such as "দূর্ঘটনা" (accident) found among both domestic and factory workers was misleading, as it conveyed that the perpetrator neither had the responsibility nor the volition that resulted in the sexual crime. The lack of clear and specific expressions identifying sexual harassment undermines the severity of the offences. Intead of specific sexual phrases, young women used generic terms relating to violence. Avoiding terms with sexual connotations, women resorted to Bangla words such as "অত্যাচার" and "নির্যাতন" meaning "torture" and "violence", rather than more explicit vocabulary.

Talking about sexual harassment women of both categories of workers commonly used the terms relating to "honour" and "shame". Shame ("lajja" or "shorom") is supposed to be felt by women when they are looked at or commented on, and this was mentioned by many of our interviewees. In the language used, women were therefore taking the blame away form the perpetrator and assuming the responsibility for the various incidents.

Enabling and Limiting Factors for Voice and Action

Both domestic and agro-processing factory workers rely on prevention and self-protection strategies to avoid sexual harassment at work or on the way to work. These strategies, either individual, collective, or both, are a form of agency. Domestic workers emphasized individual strategies, while factory workers elaborated on their collective strategies.

The workers have some common individual strategies. These include keeping quiet and not talking back; keeping one's eyes down, not looking men in the eye and keeping the body covered. A 20-year-old domestic worker said, "I do not talk with people. And even if someone says anything to me, I do not reply to them. I pass by quickly. Even if I saw my father pass by me, I would not talk with him. I do so because of shame. I am a modest person, otherwise I would have gone with people when they proposed me. Many people proposed or called me when I was passing them".

Common prevention strategies for factory workers include walking and staying together. The factory management also takes various steps to ensure that women and men do not talk to each other to limit social interactions between them because it is considered inappropriate. For example a 19-year-old firm worker said, "When we do night shift with them, they don't allow us to go outside the factory. They say-'never go outside at night alone'".

Most workers used informal complaints mechanisms in dealing with incidents of harassment. Some factory workers mentioned that if they face any harassment at or on their way to work, they would complain to their male family members who may take action such as reprimanding the offender or beating them up. Complaining to the employer or having the husband take action seems to be an informal mechanism used by domestic workers. A 19-year-old firm worker described her reaction to an incident: "We said to him that we are not alone and that we will not even complain to the sir; we have brothers and fathers outside. So then he apologised saying he misunderstood. After that it didn't happen further. Some boys do understand and stop doing it but some are bad, then we tell our male guardians". Participants of the Focus Group Discussion mentioned that both male and female workers could complain to their superiors who would take informal action.

Formal complaints mechanisms are absent for domestic workers. Factory workers can go to the administration or human resources sections, but none had done so. Going to the police, court, or local elected leaders was dismissed as inaccessible, costly, and unrealistic. They believed going to formal institutions like the court or police would require money, as rich people manipulate the system with money and power. Social respectability would also be at stake if they filed formal cases.

The poor, lower class—those who can't protest, they have to tolerate. Where can they seek justice? If they seek justice then they have to pay money first. Those who don't have money they have to tolerate.

Family support (brothers, sisters, husband), support from neighbours, and even support from households where the harassment is taking place facilitate the process of women complaining. Some women felt unable to talk to their families and husbands because of the shame or fear that they would be asked to stop work. Others reported talking to other women or family members for some mental support. Many factory workers and some domestic workers were able to seek advice from others in their situation. And in a few cases, the employer of a domestic worker was able to take action against harassers.

The research findings show how important it is to have effective workplace policies and practices to support the voice and capacity development of female workers so they can lodge complaints to their employers and approach institutional actors such as the police. Improving safeguarding measures and strengthening young women's civic and political capacities are essential for negotiating safety at work. These are currently ignored by employment and private sector interventions.

However, in being able to voice their concerns and compaints, women need to have easy and accessible language and vocabulary to describe sexual harassment, which can be used by people from all backgrounds and ages to accurately describe what they experienced. This is critical both for the person experiencing the harassment and wanting to complain as well as for the administration and management, police, legal communities and civil society organisations.

In addition, it is necessary to train domestic and agro-processing workers on provisions in the labour law and guidelines on workplace sexual harassment prevention and protection. It is also important for civil society organisations and trade unions to support female workers to strengthen their civic and political capacities and develop the confidence and courage to demand their rights and speak out if incidences occur. They will also need the capacity to negotiate social support from their fellow workers, trade unions and family members, to make and follow through with their complaints. There is also a need for every workplace, formal or informal, to have sexual harassment policies and user-friendly reporting systems, for any worker to access easily and get speedy results.

Maheen Sultan is Senior Fellow of Practice, BRAC Institute of Governance and Development.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments