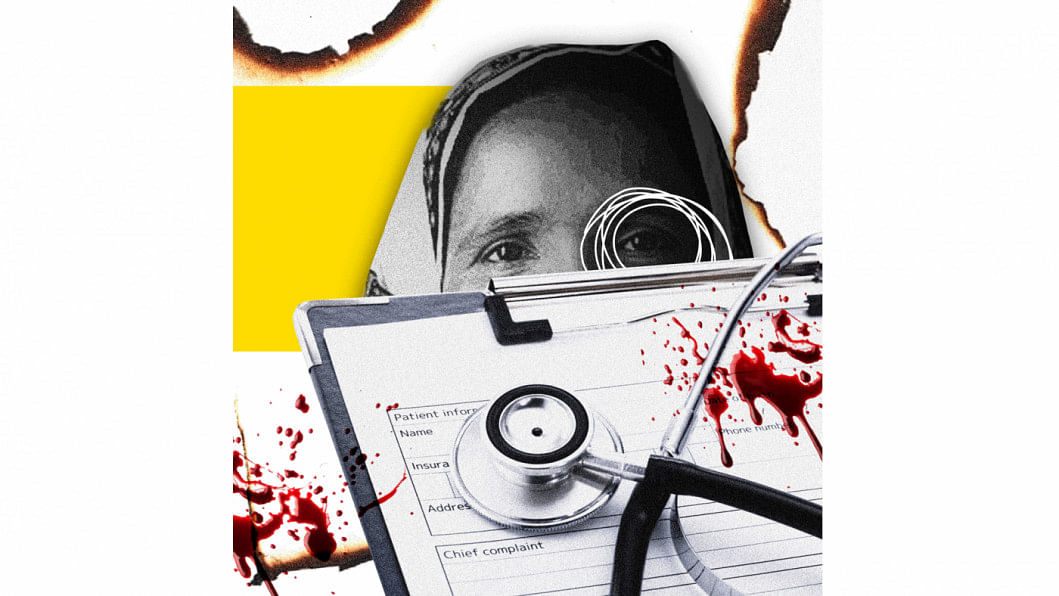

How medical evidence is used to discredit rape complainants

In October 2020, thousands of enraged protestors took to the streets of Dhaka after a gruesome video of a woman from the South-eastern district of Noakhali being gang-raped went viral on social media. Public outrage about the widespread impunity with which rapes occurred was already common, but the video caused it to reach a fever pitch. The government hastily responded by reforming the Suppression of Violence against Women and Children Act 2000 (VAW Act) and reintroduced the death penalty for single-perpetrator rape. This reform was widely (mis)interpreted as "introducing" the death penalty for rape and therefore served a largely symbolic function since the death penalty was already an available punishment for gang rape (and therefore the Noakhali rape case) under the VAW Act. What this reform should have done was address the longstanding protection gaps in rape legislation perpetuated by colonial legal provisions.

One such impediment is the colonial rule of corroboration, which requires judges to verify the truthfulness of a rape complainant's testimony with other evidence. Usually, medical evidence is given higher probative value than the complainant's testimony and can even be used to contradict it. The corresponding rule of resistance in turn guides how the rule of corroboration takes on a scientific character, whereby injuries in specific parts of the complainant's body are sought by doctors and judges as corroborative "signs of rape". If no "signs of rape" are found, this observation is then noted in the medical report and used to discredit the testimony of a rape complainant, by indicating that either the sexual intercourse was consensual or the rape accusation is false. This gives birth to what I call the "science of disbelief" in rape cases, whereby the institutional disbelief in a rape complainant's testimony is justified on ostensibly scientific grounds and largely restricts their right to seek justice. While "justice for rape" remains a common public demand, why medico-legal evidence should be the primary basis on which justice for rape is achievable, or how the science of disbelief has been preserved through successive reforms, is something that has escaped scrutiny.

The overreliance on medico-legal evidence, informed by puritanical and colonial assumptions, sets an almost unattainable evidentiary standard which most rape complainants will simply not be able to meet and therefore will effectively be denied the right to receive justice.

In British India, the "rule of corroboration" came to be established, whereby judges insisted that the testimony of a rape complainant would not usually be enough to convict a man of rape, and must be corroborated with other, more reliable evidence. It is against this backdrop that medico-legal evidence (or more specifically, the idea of "signs of rape") was developed in such a way so as to give a scientific character to the law's disbelief against a rape complainant. This distrust results in the overreliance on medico-legal evidence in rape cases, where rape is treated as a question of science, rather than a question of law. The overreliance on medico-legal evidence, informed by puritanical and colonial assumptions, sets an almost unattainable evidentiary standard which most rape complainants will simply not be able to meet and therefore will effectively be denied the right to receive justice.

Major Collis Barry in his early twentieth century book titled 'Legal Medicine (In India) and Toxicology' identified four "signs of rape" that should be searched for during a medical examination: (i) signs of infection; (ii) signs of injury to the body; (iii) signs of seminal fluid or blood; and (iv) "signs of defloration", including bruising of the genitalia and the condition of the hymen. However, it is Indian forensic doctor Jaising Modi's canonical textbook titled Medical Jurisprudence and Toxicology (1902) which had a lasting impact on rape jurisprudence in the Indian subcontinent. Modi advanced the colonial legacy set by his British predecessors, but his local adoption gave these discriminatory assumptions against a rape complainant a veneer of native legitimacy. He regurgitated the Hale warning and disbelief towards rape complainants in a more unabashed fashion and similarly treated them as having a default state of dishonesty. He casually stated that in the "majority of rape cases" relating to adult women, the complainant makes the accusation "with the object of blackmail" or to "get herself out of the trouble" when consensual intercourse is discovered (p. 244).

Modi essentially instructed doctors to pay attention to precisely those four "signs of rape" identified by Barry. In prescribing what kind of injuries to the body should be found on rape victims, he stated:

The body, especially the face, chest, limbs and the back should be examined for marks of violence, such as scratches and bruises as a result of struggle. If present, they should be carefully described as regards their appearance, extent, situation and probable duration. Such marks are more likely to be found on the bodies of grown up women, who are able to resist, than on the bodies of children who are incapable of offering any resistance.

This decisive paragraph may be viewed as the establishment of a "rule of resistance" which would be most decisive in helping doctors and judges understand whether "signs of rape" could be found on the body of a rape complainant so that they could in turn decide whether rape had in fact taken place. By analysing Indian jurisprudence and legal practice, Pratiksha Baxi, in her book 'Public secrets of law', describes the prevalence of the presumption of falsity in the creation and interpretation of medico-legal evidence as the "medicalization of falsity" which is a "specific combination of power and knowledge" and authorises "the idea that science can be used to make a female body speak despite, or even to spite, her testimony" (p.61). This disbelief took on medico-legal authority through the rules of corroboration and resistance, which dictate that the word of a rape complainant is bound to be unreliable, so more reliable evidence can only be found in her body through medical enquiry. This, therefore, gave the two rules a kind of thinly veiled scientific authority to cloak their apparent impartiality, giving birth to the "science of disbelief" in rape cases.

In 2010, the UN's handbook for legislation on violence against women condemned the rule of corroboration as being "based on the belief that women lie about rape and that their evidence should be independently corroborated" (p.43) and called for legislation abolishing the rule. It also recommended legislation to specifically state that "medical and forensic evidence are not required in order to convict a perpetrator" (p.41). Subsequently, a toolkit titled 'Strengthening the medico-legal response to sexual violence' issued by the World Health Organization stressed that penetration of the adult vagina or anus does not result in injury in most cases and that the hymen is a "poor marker" of virginity in post-pubertal girls. Unfortunately, the rule of corroboration and overreliance on medico-legal evidence have escaped various reform efforts in Bangladesh and the science of disbelief remains well preserved.

As a member of the technical committee under the Rape Law Reform Coalition, I began reviewing Supreme Court jurisprudence on rape under the VAW Act to understand the extent to which judicial attitudes perpetuate impunity for rape. The Supreme Court of Bangladesh comprises two branches: the High Court Division (HCD) and the Appellate Division. A rape case is usually tried before the VAW Tribunal and the Tribunal's decision may be challenged before the HCD through appeal. After reviewing rape cases filed under the VAW Act which were reported in six leading law reports between 2000 and 2019, I discovered 44 rape cases where the VAW Tribunal's decision was challenged. In 43 of these 44 cases, the defendant appealed a conviction by the Tribunal, while in the remaining case a rape complainant challenged an acquittal by the Tribunal. One of the most common grounds of appeal by the defendant was the argument that the medico-legal evidence produced by the prosecution was not enough to prove rape. In 25 out of these 43 cases, the Supreme Court accepted the defendant's challenge, reversed the VAW Tribunal's decision and ruled that rape had not taken place.

This widespread presumption guided the colonial law of evidence and gave birth to the pernicious rule of corroboration, which mandated that the sole testimony of a rape complainant would not usually be enough to convict a man of rape, so there must be other, more reliable evidence to corroborate her statement.

In the case of Sree Pintoo Pal vs. State (30 BLD 2010 220) the doctor stated in the medical report that "no sign of recent sexual intercourse is detected" but was not examined by the prosecution, while the apparel of the complainant was seized but not chemically examined. Therefore, the Court referred to the earlier case of Seraj Talukder vs. State (3 BLC 1998 182) where the Court had held "absence of sign of rape in the medical report and non-examination of the wearing cloths made the whole case most doubtful one". The Court also referred to the much older case of Shan Khan vs. State (18 DLR 1966 91, para 38) decided by the High Court of West Pakistan in 1951, wherein the paragraph in Modi's book establishing the rule of resistance was cited: "In the case of rape, according to the Modi's Medical Jurisprudence, the body specially the face, breasts, chest, lower part of abdomen, limbs and back should have marks of violence such as scratches and bruises as a result of struggle. Such marks are likely to be found on the bodies of grown up women who are able to resist."

Thereafter the Court held that medical report is a crucial factor which impacts "the entire case" and the medical report in this case, coupled with the non-examination of the apparel and "absence of scratches and bruises in face, breasts, chest, abdomen, limbs and back" did not support the allegation of rape (para 39). Notably, the Court accepted that it is a "settled principle" that there is "no legal bar" to relying on the sole testimony of a rape complainant, if it is found to be "reliable and worthy of evidence" (para 41). However, the fact that the complainant in this case climbed a paupa tree to enter the house of the accused the day after the alleged rape took place, "proved that she was a woman of easy virtue, so her evidence cannot be believed without the corroboration of reliable evidence" (para 40).29 As we can see, in this case the science of disbelief prevailed, necessitating the rule of corroboration and the rule of resistance, neither of which were met and therefore the defendant was acquitted.

For centuries, rape complainants have been subject to disbelief not just by society at large, but also by the legal system that is meant to be the impartial forum for attaining justice. This widespread presumption guided the colonial law of evidence and gave birth to the pernicious rule of corroboration, which mandated that the sole testimony of a rape complainant would not usually be enough to convict a man of rape, so there must be other, more reliable evidence to corroborate her statement. In this context, medico-legal evidence was developed in British India as the central way in which to corroborate rape complaints, with doctors being trained in the science of searching for "signs of rape" in the body of the complainant. This search has essentially been guided by the rule of resistance which dictated that a "real" rape survivor would have clear "signs of rape", meaning marks of injuries on certain parts of her body, as a result of resisting her attacker to the utmost extent.

As I have attempted to show above, the twin rules of corroboration and resistance gave birth to a science of disbelief which continues to shape both medical and judicial opinion in Bangladesh. The need for corroborative or medical evidence to prove rape (and therefore these two rules) violates the global standards set by the UN and the WHO. Legal reform is seldom enough to catalyse social change. However, doing away with these two rules would go a long way towards ending impunity for rape by eliminating the pernicious science of disbelief which has enjoyed a longer life than it deserves.

Taqbir Huda is legal researcher currently pursuing an MSc in Criminology and Criminal Justice at the University of Oxford.

This piece is based on (slightly edited) excerpts from the following journal article: Taqbir Huda, '"No signs of rape": corroboration, resistance and the science of disbelief in the medico-legal jurisprudence of Bangladesh' Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters (2021) Volume 29 Issue 2, pp. 436–448.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments