What makes a classroom great?

In face of the challenges with learning and teaching in the 21st century, creating a classroom that is a perfect hub of knowledge-sharing requires some careful considerations. In the third part of a series that focuses on some of the most basic and important issues of higher education in Bangladesh, three veteran educators explore the elements that turn a conventional classroom into the optimal space of learning. The Daily Star welcomes and encourages any and all thoughts, ideas, and recommendations regarding these issues from our respected readers.

A great classroom is one that is conducive to learning. Let's unpack this statement.

What are the most important components for one to learn something? Well, they can be sorted into two broad categories: internal/intellectual and external/physical.

The most important internal/character quality (based on research) that helps most in learning is curiosity, and the most important physical quality that fosters learning in the classroom is its environment or the ambiance. Curiosity is something that needs to be nurtured from the earliest years, as discussed in the previous article. Let's then talk about creating a physical classroom environment that can encourage learning.

Above all, a classroom should be safe and comfortable. "Safe" means that each and every student entering a classroom (or any educational institution) should feel completely safe from any threat – physical or emotional – from anyone including their teachers and cohorts. "Comfortable" means a student must have enough space around him/her to feel physically uninhabited and relaxed enough to be able to open up his/her mind to receive the learning.

Safe and comfortable also means a clean and well-maintained classroom – one that has appropriate lighting, proper temperature, and is protected from outside noise, pollution, and foul odours. Proper acoustics is vital if the classroom intends to accommodate a larger-than-average number of students. Heavy wooden chairs, tables, desks, and other furniture seen in a typical classroom in Bangladesh can not only be hazardous (for example, in case of a fire when the students might need to leave the classroom quickly) but a nuisance as well. Each time a chair needs to be moved, there's a squeaking noise that can stop the classroom conversation for a few seconds; each time a late-arriving student walks in, a series of desks need to be rearranged and the chorus of clangs and bangs continue for a couple of minutes.

A great classroom is one that is conducive to learning. Let's unpack this statement. What are the most important components for one to learn something? Well, they can be sorted into two broad categories: internal/intellectual and external/physical. The most important internal/character quality (based on research) that helps most in learning is curiosity, and the most important physical quality that fosters learning in the classroom is its environment or the ambiance. Curiosity is something that needs to be nurtured from the earliest years, as discussed in the previous article. Let's then talk about creating a physical classroom environment that can encourage learning.

These disruptions, when repeated often and continuously (which is so typical that I wouldn't be surprised if a survey reveals that more than 10 minutes out of a normal 55-minute teaching time is lost in the process), can have a definite and detrimental effect on learning.

Next, a classroom that is conducive to learning must have its seating arranged in a way that each and every student gets the full view of what's happening in the teaching process: from being able to see the professor at his/her full length, face all fellow students in the classroom, to being able to see the monitors, the projection boards, the writing space – everything! In a typical seating arrangement inside a typical Bangladeshi classroom, other than the first-row students, no one gets the full view of the instructor (unless he/she moves around – which is also a rare phenomenon), no student gets to see more than a fraction of other students. Students in the back rows may not even hear what a student from the front row is saying/asking. Rarely, if ever, have I seen a classroom that can simply be rearranged for every student to be able to see the others, for the teacher to have enough space to move around, and for the visuals to be right in front of students.

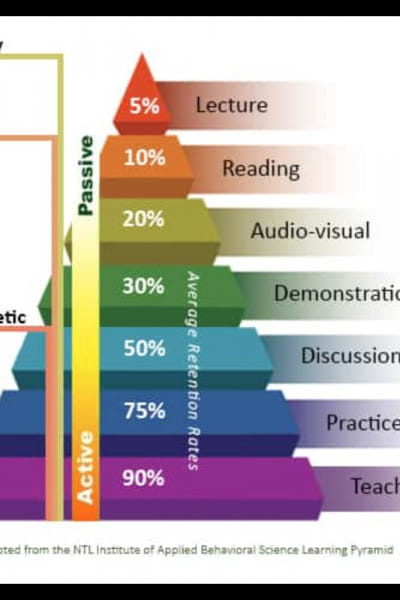

A great classroom must have tools to "show" students more than to "tell" – dictate, narrate, describe, and so on. It must also have the ability for the students to get up from their seats, move around, discuss the learning material with others and be able to rehearse with/teach others. The Learning Pyramid, developed by the National Training Laboratories Institute in the United States, states that students remember only 10 percent of what they read from text, but retain almost 90 percent of what they teach others. This model suggests that, for deep and long-term learning, students must have the tools and space in the classroom to practise teaching.

Designing a great classroom must be the product of a thoughtful decision-making process: who are we teaching, how, and for what purpose? Are we allowing students to take centre stage in this space, or are we letting instructors play the dominating role? A poorly designed classroom will not produce good learning. A well-thought-out classroom, on the other hand, will bring joy and spontaneity among the learners, foster the spirit of learning, and make for happy and deep learners.

Dr Halimur R Khan is a university professor and can be reached at [email protected].

***

Obviously, ideal classrooms are discipline-specific and defined by instruction levels. For upper-division offerings in the social sciences, arts and the humanities, a good classroom must facilitate interaction, allowing teachers to ask questions, invite discussions, and create a dynamic and lively atmosphere.

Teachers must be able to get off their "pedestals" to make students feel less intimidated and more validated. These pedestals can be both physical and psychological, and may serve as alienating devices that limit the imagination of students, invoke fear rather than respect, and disrupt the mental quickness and fluidity that is vital to provoking, as well as satisfying, their curiosities. Simply being identified by name by the teacher may change the students' perceptions, and often their performance, in terms of a course. Students should also be able to address each other to initiate debates and discussions, clarify ideas, share information, present personal reflections, and foster a spirit of fairness, academic freedom, and inclusiveness.

But this environment of meaningful and productive engagement between professors and students depends on a pre-condition that must be fulfilled – the classrooms themselves must be conducive to a good learning experience. Thus, lighting, seating, airiness, cleanliness, acoustics, and other "material" conditions (such as the infrastructure of pedagogical paraphernalia, teaching tools, and appropriate technology) all become factors in making teachers and students feel welcome, comfortable, and supported. This demands adequate space, but also seating arrangements different from the usual rows of desks extending deep into the classroom (which may also nurture the "back-bencher" or, conversely, the "favourite student" syndromes).

In Bangladesh, these vital aspects of education usually receive insufficient attention.

University officials typically brag about the number of PhDs they have hired, the number of GPA-fivers they have admitted, or the number of students they have graduated. This probably indicates the misplaced nature of the priorities within which they function, and the misleading nature, if not the futility, of the numbers-obsessed ranking/rating systems they embrace. After all, they know full well that no one will come in to check on the quality of their classrooms.

Many universities are housed in older and apparently unkempt establishments where electric fans may be dysfunctional, air conditioners louder than they are efficient, lighting insufficient, outside noise distracting, and more students crammed into spaces than originally intended. The emphasis is usually on the lowest common denominator that will allow decision-makers to deflect or escape "blame," and to manage with what is "good enough" rather than create what is "good."

Public university authorities may occasionally give the impression that simply operating the institutions and providing classrooms are, by themselves, great favours they are bestowing on students and society. (Their pulse quickens only if there are "megaprojects" where they can expect some crumbs to fall on their plates as well.) On the other hand, a few private universities, at times functioning on business models which emphasise short-term cost-benefit calculations fixated on the immediate hypothetical "bottom line," may remain blissfully – at times deliberately – indifferent to these imperatives.

University officials typically brag about the number of PhDs they have hired, the number of GPA-fivers they have admitted, or the number of students they have graduated. This probably indicates the misplaced nature of the priorities within which they function, and the misleading nature, if not the futility, of the numbers-obsessed ranking/rating systems they embrace. (After all, they know full well that no one will come in to check on the quality of their classrooms.)

The spatial organisation of the room, its physical geography, its internal design and architectonics, all play a not-insignificant role in supporting and shaping the shared intellectual journey of discovery, joy, and fulfilment in which the students (as well as the professors) have collectively embarked. These factors alone cannot promise a sufficient condition to ensure their personal and professional growth, but certainly a necessary condition in furthering those objectives.

Dr Ahrar Ahmad is professor emeritus at Black Hills State University in the US, and director general of Gyantapas Abdur Razzaq Foundation in Dhaka.

***

A great classroom has two teachers. We all know the first one who stands before the students and inspires them with his/her knowledge. The second is the classroom itself – the space of our learning. We are often oblivious to its profound influence on us. Defining the second "teacher" is not easy because it has multiple dimensions, among which are its physical environment and social climate.

The physical environment of the classroom can narrate a lot of stories about us, our attitude to learning, and the world we inhabit.

Rabindranath Tagore envisioned Shantiniketan (meaning "the abode of peace") in the image of traditional Indian hermitages, which took shape in the forests of ancient India, arguing that the best humanistic learning is possible only when it occurs in harmony with nature. Tagore introduced an eco-psychological concept of nature to explain how the forest symbolises the "diverse processes of renewal of life" and the precious freedoms that define it. In his 1909 essay "Tapoban" ("forest of purity"), he wrote, "India's best ideas have come where man was in communion with trees and rivers and lakes, away from the crowds. The peace of the forest has helped the intellectual evolution of man." In other words, the learner is most active and imaginative when in a natural environment – or at least in its best simulation.

Are Tagore's ideas still relevant today? Possibly, as an inspiration. Today's designers of schools may not situate a classroom in the forest, but they endeavour to capture its spirit in the form of natural light, natural ventilation, proximity to greenery, use of natural building materials, and, most importantly, an ethos of openness.

Around the world, designing a classroom today means designing well-being, sustainability, environmental resilience, recyclability, and renewable energy adaptiveness, among other factors. The organicity and innocence of the educational Garden of Eden that Tagore dreamed of for Shantiniketan could be a great policy lesson in creating the classroom of the future. Irrespective of what a student is studying, the physical set-up of the classroom must be inspiring, while also being safe, comfortable, and well-equipped. A space is inspiring when its experience induces a feeling of ecological consciousness and reminds the students of the need to be good citizens.

Rabindranath Tagore envisioned Shantiniketan (meaning "the abode of peace") in the image of traditional Indian hermitages, which took shape in the forests of ancient India, arguing that the best humanistic learning is possible only when it occurs in harmony with nature. Tagore introduced an eco-psychological concept of nature to explain how the forest symbolises the "diverse processes of renewal of life" and the precious freedoms that define it. In his 1909 essay "Tapoban" ("forest of purity"), he wrote, "India's best ideas have come where man was in communion with trees and rivers and lakes, away from the crowds. The peace of the forest has helped the intellectual evolution of man." In other words, the learner is most active and imaginative when in a natural environment – or at least in its best simulation.

The social climate of the classroom is of utmost importance, too. Classrooms should teach us to be empathetic, community-oriented, and socially conscious. The ideal classroom is one that is gender-sensitive, equity-driven, and affords each student agency in the learning process by recalibrating the traditional uber-primacy of the teacher in the classroom matrix. The spatiality of the ideal classroom and its social environment should empower all students – irrespective of their economic class, gender, and religion – to think that each of them has a role to play in creating an equitable and healthy domain of learning.

As there is no universal formula for an ideal classroom, each university can prioritise configuring classrooms flexibly to inspire learning as a foundational act of worldmaking and an appreciation for democracy. Having a clean, accessible, and gender-friendly toilet – not far from the classroom – is an expression of social justice, spatially inscribed.

But how about technology in the classroom of the 21st century? How would the era of artificial intelligence or ChatGPT intersect with the idea of tapoban? The ideal classroom should be properly equipped with user-friendly audio-visual systems and other learning-focused technologies, insofar as technology serves as a tool to facilitate learning itself. In fact, research shows that classrooms in countries with the highest-performing students hardly feature technological marvels.

Having recently read The World Is Our Classroom: How One Family Used Nature and Travel to Shape an Extraordinary Education by Cindy Ross (2018), I am tempted to think that the best classroom is the one that knows how to break free from the intellectual claustrophobia of four walls. Such a classroom stops being a room, de-centres the learning process, and embraces the world and its immeasurable diversity as a free school out there.

Dr Adnan Zillur Morshed is an architect, architectural historian, urbanist, and professor. He teaches at the Catholic University of America in Washington, DC, and serves as executive director of the Centre for Inclusive Architecture and Urbanism at Brac University.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments