Bangabandhu through the eyes of Japanese filmmaker, Nagisa Oshima

The most important chapter in the national history of Bangladesh is the Liberation War of 1971. Millions of people in this country participated in the bloody war irrespective of age, sex, class, religion, caste, and ethnic identity. Many documentary filmmakers and the international media, in general, came to this war-torn land during the war. The Western media and films mostly gave more importance to the compilation of the tragic scenes of the Bangladeshis being tortured, raped, robbed, and killed by the Pakistani army rather than the images of their strong resistance in the war.

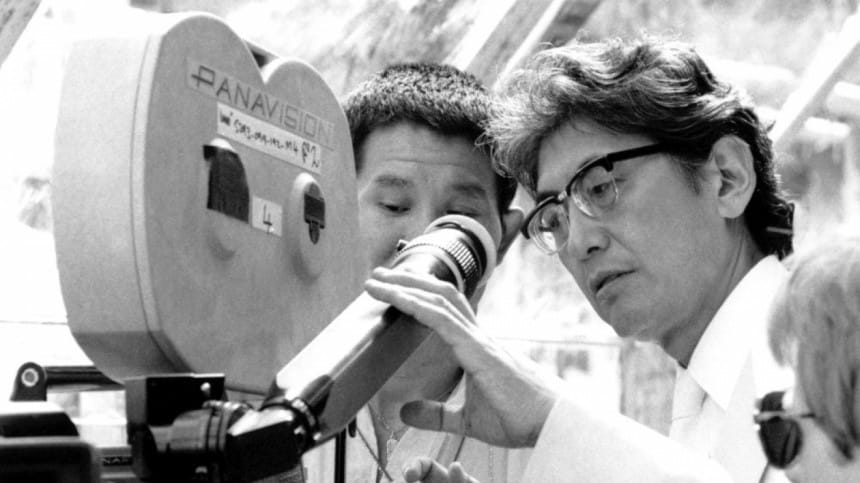

The Japanese film director, Nagisa Oshima is a glaring exception. Primarily known for his New Wave style of filmmaking, in many cases, Nagisa Oshima has brought up rebellious and underprivileged youths in his films. Compared to the usual subject matters of his films, it is interesting to see that his two documentaries focusing on Bangladesh, Joi Bangla (1972) and Rahman: Father of Bengal (1973), are different. He finds the intense glory of Bangladesh's achievements in the context of 1972-73 even when the country was in a war-torn condition following the war in his film Rahman: Father of Bengal.

The country had just become independent. Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman had returned home. Although the people of this country were able to achieve independence, there also prevailed a state linked to the memories of war, sadness, and uncertainty about the future.

What does the leader of the country, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman think about his nation in such a turbulent time, how will he lead the country to move forward, how does the past give him incentives, and how will he be acted as the father both in the family and state life — many questions like these are asked to Bangabandhu.

At the same time, topics like Bangabandhu's political activities, favourite books, his views on Bengali nationalism, marriage, family life, how his family was a victim of Pakistani violence during the war, and his visions and dreams about the country — issues as such are also discussed in this documentary in a conversational manner between the film director and Bangabandhu.

Although this documentary film Rahman: Father of Bengal is focused on Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, at the beginning we see that Nagisa Oshima captures the waterways of Bengal. He creates the riverine landscape of this land through voice-over narration, using folk songs, local musical tunes, and images of people of various professions travelling on the waterways.

He also rides on a steamer. The destination of the water journey of Oshima is Bangabandhu's birthplace, Tungipara, where it takes him one day and one night to reach from Dhaka. The fare of a steamer is Tk 4 (or 160 Yen in Japanese currency), while a day's wage of a common labourer is Tk 3 taka (120 Yen) — such a topic also appears in his narration revealing the reality of Bangladesh in the context of 1972-73. Slowly different scenes depicting the steamer journey were emerging: the crowd of people standing in piles on the steamer, small and large boats floating on the river bed, steamer passengers such as two children standing in the arms of a veiled mother, and some ordinary people praying in the late afternoon.

The voice-over narration points out that even though religious sentiments are strongly embedded in the minds of the people of this region, the constitution of this country is rooted in secularism. The next few scenes show Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman together with his councilors praying at the founding ceremony of the memorial tower for the deceased of the war, placing wreaths on the memorial tower after the prayers, and then ending Bangabandhu's speech at a public meeting with the slogan 'Joy Bangla'.

Thus, Oshima portrays the leader of the people initially through the embodiment of the people's way of life — a life in which both the religious belief and the strong impulse of secular Bengali nationalism are drawn breath.

Then Oshima presents a historical event — 16 December, 1972. This was the first anniversary of the Victory Day of Bangladesh.

We see Bangabandhu taking oath as the Prime Minister according to the new constitution, together with President Abu Sayeed Chowdhury. Then, for the first time, we see the interview of Bangabandhu. He talks about his youngest son Russell and how his parents were victims of Pakistani violence during the war. The scene changes again. We see Oshima heading towards Tungipara on the steamer. His camera captures the fascinating sceneries of the riverside accompanying the folk song as the background score. The voiceover narration goes on to create a storytelling mode. In this way, this documentary, across its large area, cuts between the journey of Oshima and other sequences taking interviews of Bangabandhu and his activities at home and outside.

The filmmaking technique of this documentary does not tend to create artificially created tidy forms. In conventional documentaries, a kind of illusion of reality is created by the inclusion of scenes and interviews with the narration of an unseen commentator. In contrast, Oshima wants to clarify that this reality is also a kind of construction. At the moment of filming, the positioning of Nagisa Oshima and the interpreter on the left side of the frame (with a partial back view) in some scenes, especially when interviewing Bangabandhu, indicates a way of depicting the process of filming following the features of 'Direct Cinema'.

Direct cinema is a genre of documentary filmmaking that originated in the 1960s in North America and the Canadian province of Quebec, giving independent filmmakers an irresistible incentive to produce realistic films at low cost. It avoids the use of invisible and imposed background voices or sound effects. The use of lightweight cameras and technical equipment, exclusion of studios, use of synchronised sound, and operation of a lightweight camera by placing on the shoulders instead of a tripod — are some features of the films of this genre. In Rahman: Father of Bengal we also find some aspects of direct cinema.

Most of the scenes in this documentary were shot using a hand-held camera. In many cases, the camera is shaky in capturing the truth of the incident instead of taking the shot in a neat form. For this reason, in many scenes of this film, especially towards the end, when capturing the public meeting scene, the camera is scattered in different directions to capture the tide of the crowd.

Many filmmakers, interested in creating a traditional documentary concept, might dismiss these shots captured by a hand-held camera as N.G. (not good) shots. However, these scenes are presented in a uniquely artistic way in the film following the attribute of direct cinema for grasping reality.

The film presents many important topics of Bangladesh's history in a simple way: Bangabandhu taking oath as Prime Minister, an ordinary depiction of Bangabandhu and his family's simple home life at the breakfast table, his exchange of words with general people, Bangabandhu's spontaneous speech in the presence of hundreds of thousands of people of various classes and professions in several public meetings, Bangabandhu's special attachment to his seven-year-old son, Russel.

At the same time, the clarity of Bangabandhu's political ideals and self-styled conversational style in answering many questions ranging from simple to important political questions, also become evident. The documentary shows — a dilapidated primary school in Tungipara where Bangabandhu studied; the fact of his ancestral home being burnt down by Pakistani troops in 1971; the scene of his father Sheikh Lutfur Rahman praying in a temporary and ordinary house in Tungipara; and the wishes of his father to live with his son and grandchildren here in this village.

Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur, an extraordinary man who came from a very ordinary home, will build Bangladesh — we see the bright expression of this assertion throughout this film. At the end of the film, it is said: "The past, the present, the future of his [Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman's] life are entirely dedicated to Bangladesh."

Indeed, history has painfully witnessed the words of Nagisa Oshima. This great person who snatched freedom for Bangladesh was killed in this country, within two years of the making of this documentary.

Being the Father of the Nation, he kept the nation alive through his service until the last day of his life. But he could not go back to his village to fulfil his own father's wish to live with him.

The writer is a Professor of Drama and Dramatics, Jahangirnagar University.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments