On belonging

There's something about moving – whether it's to a new town or a new continent – that always makes me seek out the familiar. And although I don't always notice when I'm doing it – or feeling it – this morning, when it starts to rain in Dhaka for the first time in months, wonderful light, clean rain, I find myself standing on the balcony, breathing in the scent of damp leaves and being transported back to the straggly meadows near where I grew up in England that seemed to shimmer after the rain, revelling in their bright green-ness. I remember the fields so clearly that I can almost taste the tinny wet-earth smell and feel the slippery mud that squelched under my shoes. For an instant it's as though I'm there again, back in a place where I felt like I belonged.

Yet I wonder about belonging. Where its joy and relief live in my body. And whether it's also responsible for the moments of loneliness I've struggled with over the years – moments of disconnection and isolation tinged with sadness.

The first time I left London to live overseas with my young family was when we moved to the Caribbean with my husband's job. Everyone back home thought we'd won the relocation lottery and would repeatedly tell me how envious they were of the fact that I got to live next to white sandy beaches and take the kids to paddle in the clear, warm, turquoise sea after school.

Barbados was, and is, a stunningly beautiful island. Yet I struggled with homesickness. I missed my mum, my sisters and my friends – people who made me feel grounded, supported. I wasn't used to seeking out the familiar and became disconnected from myself, struggling to find a way back.

There was also a heaviness to the place. A dark atmosphere that felt particularly strong when I drove through the interior of the island, along narrow roads that cut through winding fields of sugar cane to the east coast, and stood on the shore looking out over the Atlantic. I later learned that's where the slave ships used to come in, ships that contained people chained together for weeks in horizontal rows, packed in layers like dead fish – many of whom were dead by the time the boat landed.

The survivors are the – relatively close – ancestors of those who now belong to the island, its soft sea breezes and rangy coconut trees, its legacy of derelict cane factories and its dark history. Despite this deeply traumatic beginning, people who call themselves Barbadian today have accepted the land as theirs. And in a sort of enforced yet tender adoption, they, like many of the world's displaced people, have found themselves in the land, a home. And after four confusing, beautiful years on the island, I finally felt at home there before moving again, to Africa.

So, what, then, is home? This is a question I often ask my children who have spent more than a decade living away from the nation emblazoned across the cover of their passports. And the answer is usually mixed. It's part wherever our family of five currently has a home, part sitting under the apple tree in their grandparent's garden on a summer's day and partly the taste of Barbadian sugar syrup and lime, or the familiar sight of the enormous amber Botswana sun slowly disappearing on the horizon.

All of these things feel good. Good. A word which, at its Proto-Indo-European root, means "to unite, be associated with," and ultimately, to belong. It feels good to belong and it feels good to be connected. But to whom do we belong and what is it that connects us?

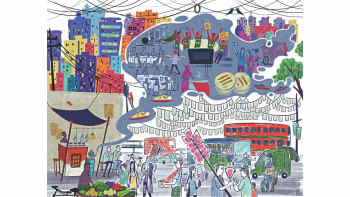

I wonder about this when I find myself moving through Gulshan one day on a rickshaw. I pass a tea stall, noticing how tired and relieved some of the men gathered on the pavement look, how I've seen that look on faces so many times before, and I watch as a battered bus slows down and a frail old man starts to get off and nearly falls to the ground before a crowd of people rush over to help him. Then there is a dog lying asleep in the road near my building, unflinching, completely relaxed as the cars and rickshaws veer around her. As the evening call to prayer begins, a plaintive song that reminds me where I am, over and over again, I notice how witnessing these interactions makes me feel connected, safe. And I remember that everything changes when I see that we all belong to the world and to each other – that this is what connects us.

There is an amazing abundance of green beside Lake Baridhara right now. Skyward palms, teak trees covered in vines, shrubs and ferns line the path, yet while walking there the other day, I stopped in my tracks when I saw that, among the sea of emerald shrubs, was a bright purple bush that looked so out of place I wondered if it had been spray painted as a joke. As I stood there gazing at it in all its purple glory, I realised this plant made everything else even more beautiful just by being there.

Because, when you focus on difference, there it is – everywhere. Yet when you see all of the tiny imperceptible threads that connect everything, you realise that life is a shared experience. One where we make and remake ourselves through each other, over and over again.

Yvonne Gavan is a writer, journalist and host of The Tenderness Revolution podcast, currently based in Dhaka.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments