Before Trashing the Trash Culture…

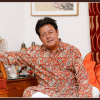

One noted thespian has come under public scrutiny for an off-stage speech. Theatre activist and the founder of Aranyak, Mamunur Rashid, lashed out against what he finds a "famine of aesthetic taste" that is plaguing our cultural scene. He was referring to the phenomenal rise of Hero Alom as a social media hero.

The phrase alludes to Zainul Abedin, who used the phrase in the 1950s to highlight the absence of aesthetic sensibility against which he had to paint his famous sketches on the great famines during British rule. As the founder of the Faculty of Fine Arts (established as the Institute of Arts and Crafts in 1948), Zainul's contribution to Bangladeshi modern art is immense. His generation paved the way for a "culture" with a home-grown signature. It is marked by deference from the western import of imperial culture that was confined to the colonial rulers and their local associates. The exclusivity and deference allowed Zainul to become a high priest of our culture, moving away from the cultural habits and preferences of the aristocrats. The appropriation of local figures catapults Zainul into an emerging art scene that was redefining our artistic contour. If Zainul's statement on "famine of tastes" is the birth cry of high culture, Mamun's observation is the lament over the death of such a culture.

Mamun is pained to see the growth of trash culture that has become the consequence of what was known as low culture. High culture, by design, is exclusive and accessible to an academically literate or culturally sensible audience. Low culture, in contrast, includes various types of popular culture that are characterised by their mass appeal. There are times when the boundary between the high and the low can be blurred. A commercial film with a huge public appeal can now be nominated for a Cannes award to get the high-brow seal.

The rejection of Hero Alom as a cultural entity hints at deep-seated social anxiety. It is not the first time he has been thrown out of the mainstream culture loop administered by some cultural police. In one instance, he was nabbed and humiliated by a police officer for wearing a police uniform in one of his B-movies. Alom was sanctioned for trying to sing Tagore's songs out of tune. Somehow, this self-starter uses this bad publicity to promote himself as a subaltern. He poses himself as someone who is taking arms against "the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune." He is not a prince who is born with a silver spoon. He does not have the look or social standing. Yet he has the desire for social mobility. In a democratic culture, such desire is usually encouraged. He exercised his right to be a spokesperson for the mass by becoming a public representative. He managed to give the impression that he had been wronged at so many different levels, prompting public sympathy and attention.

At one extreme, there are the sympathisers of the high priests who lament the glory days of high culture. At the other extreme, we have the defenders of Hero Alom who are critical of Mamun and co. for not allowing the downtrodden to move up the socio-cultural ladder.

When Mamun critiqued Hero Alom as a symptom of the trash culture that is eroding our cultural norms and practices, the reaction is forked. At one extreme, there are the sympathisers of the high priests who lament the glory days of high culture. At the other extreme, we have the defenders of Hero Alom who are critical of Mamun and co. for not allowing the downtrodden to move up the socio-cultural ladder. With the rise of internet users, the second group is winning the verbal battle as they are making more noise. A TikTok artist or a YouTube influencer has more followers than the number of people who would go to Bailey Road or Shilpakala Academy to watch a play.

Take the instance of the British actor Sir Ian Murray McKellen. His career spanned over six decades. He was shot to fame for his stage performances in Shakespearean dramas and modern theatre. The high-brow actor is now a popular cult figure for his performance as Gandalf the magician in The Lord of the Rings or as Magneto in X-Men films. The fulcrum of the mass has shifted.

Those who have been traditionally performing public piety must reassess their roles amid the changing culture. Hero Alom knows that there is a glass ceiling that stops someone from a humble origin to move up. His rustic accent, skinny figure, and apparently talentless performance work against him. To compensate for his shortcomings, he appeals to those in his condition: a multitude that wants to change their lot. Alam plays the victim to pose as a martyr in the culture wars. I guess, he deserves credit for his ambition. Instead of curating his artistic desire or channelling his energy into something productive, the cultural and political police have constantly side-lined him only to confirm his victimhood.

When I started attending Jahangirnagar University as a freshman student of English literature, we had many cultural activists coming from small provincial towns. They were the ones who reigned the amphitheatre, and dominated the cultural and political organisations. Those of us who travelled from Dhaka could sense the condescending attitudes they would have toward us. Likewise, we would hold them as a bit rustic to our taste. Then there were the students from the locality. Even among my friends, despite our hours of hangouts, I could sense the invisible barriers of social upbringing, cultural orientation, and economic condition. We outgrew the silent resentment by spending more time together, and by understanding one another.

The problem that we are now facing is that of subtle racism. The high brows like Mamun consider the Hero Aloms as "upstart crows beautified with our feathers," a remark that Elizabethan playwright Greene made about the rural Shakespeare who was trying to join their league. The tendency to trash the trash culture while highlighting the sweetness and light of high culture is an age-old phenomenon. It was Matthew Arnold who thought of culture as the best thoughts created by bee-like artists who gather sweet honey and waxed candlelight. Now we know the culture as a way of life, a set of practices that endeavour to make meaning for a group. The social media rebels are doing the same. They are no less different than the artists who searched for artistic meanings in life.

Instead of cancelling each other, it is time that we try to learn from each other. We are, after all, on the threshold of a huge cultural leap.

Dr Shamsad Mortuza is a professor of English at Dhaka University.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments