A life of light and perseverance

"After hardship, there will be ease"—surah/chapter: Ash Sharh; ayat/verse: 5; Al Quran, 94:5; —"this is Allah's promise, so never lose hope in times of hardship."

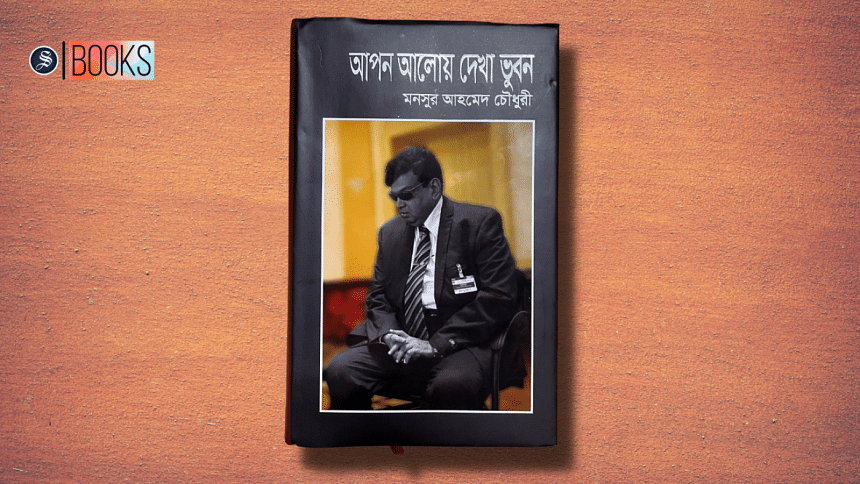

On reading Monsur's autobiography, Apon Aloy Dekha Bhubon (Shomoy Prokashon, 2022) many may have the feeling that Monsur Ahmed Choudhuri had heard Dr Bilal Ameenah Philips say this to Monsur. One cannot help but be struck by the incidents and obstacles that came his way from a very tender age. He was six when he lost the sense of sight and with that, the light to the physical world.

Monsur, in his book gives the readers a glimpse of the natural environment and social situation prevalent during his time, which he was able to see and feel then, recalling— "Gulistan theke Azimpur Riksha kore jawar rastar ashey-pashey drisho aaj nishchoi shob e bodley gechey" (the sight of the scenes on either sides while taking a rickshaw ride from Gulistan to Azimpur, has certainly undergone changes).

A boy of six or so, what would he know or comprehend about the difficulties of life? In 1957, he began school for a second time, in an entirely different place from his first school and a difficult environment to which he was a total stranger. In his book, he talks about his experience at the school of the Rotary club of Dhaka, where he had to master the Braille system. Even as a child, Monsur was selected to read from his textbook on the Braille system at a programme honouring the President of the Rotary International visit to his school, who was also accompanied by local Rotary leaders. According to his description about preparing a passage to be read out in the presence of the visiting Rotarian guests, he took it to heart and memorised it entirely.

Though differently abled, in comparison to most of his peers, one may not be aware of his limitations of sight from the kaleidoscopic narration of his eventful life, save and except, where he specifically mentions it. What a feat of retrospection and description!

While going through Monsur's autobiography, one's attention is bound to be drawn to facts about current affairs penned with meticulous precision. He conveys his experience of 1957—the horrendous experience of losing eye-sight—along with being victim to the cruelty of harsh remarks.

He recalls with fondness his meeting Ataur Rahman Khan, the then-Chief Minister of East Pakistan; Eric T Boltar, the Executive Director of the present day Helen Keller International Foundation; Sir John Wilson, and Lady Wilson in 1957. He planned the meeting to discuss transferring money from the UK based rotary clubs to Bangladesh to the development of Jibon Tori, a riverine hospital project. I am proud to have been instrumental in transferring the money through the Rotary club of Dhaka Rose Vale, for a great cause. Monsur warmly welcomed my humble offer to provide the hospital a speed-boat on behalf of my family. I remain indebted to him.

He has vividly described the environment and the engagement of his family and the others concerned in a number of situations involving his educational performance and progress. His narration also presents to the readers his interest in not only remaining steadfast in his gathering of information on various subjects, but his keen interest in sports and music as well. He indulges in these activities even to this day. His narration also spells of interest in political matters, political figures, and related occurrences.

Monsur Ahmed Choudhuri, in the chapter, 'Rotary club of Dhaka kortik shombhordona', remembers to this day his saying, "Life is not a bed of roses, for a blind person especially it is full of mighty struggle. But I want to live, I want to struggle and through this I want to show that human spirit is indomitable", a sentiment that has been proven in his glaring and varied performances and accomplishments.

His narration has a wide spectrum of experiences—from his childhood days, when he did enjoy the blessings of sight to being confronted by innumerable frontiers, such as anxiously seeking scope to education, accepting situations of having to stay in the boarding, a life unknown to him, treading on the unheard of paths, being filmed for National broadcasting, experience of being invited to meet the President of Pakistan, Field Marshal Ayub Khan for notable performance in the school final examination. He relates his journey by road to Sylhet, his journey by train to Chittagong, present day Chottogram, and his road journey to Cox's Bazar. At a later time he describes his journey by air. The book gives the annals of the social history of the country—character of teachers, family structure and relationships.

Monsur's narration is punctuated by his reference to his participating in musical soirées. He narrates that he could draw the attention of figures like Hossain Shaheed Saharwardy and Mohamed Ali, the then Prime Minister of Pakistan, through his participation in the cultural programme hosted in their honour. Monsur was touched by the affection showered on him by people of renown. He met international dignitaries from across the world.

He mastered the Braille system and by dint of his dedication, he has successfully carved out for himself a niche that covers a wide spectrum.

The book also is a casement to experiences of the Liberation War of Bangladesh, the political atmosphere, and the transition from the status of being part of a country to an independent nation. One can get a picture of the social fabric prevalent in Bangladesh from the 1050s to the present day.

Time and again, Monsur expresses his gratitude to his parents, Rotary International and the stalwarts of Rotary, and his teachers, who played a pivotal role in grooming and shaping his life. He never needed to ask: "What is that thing called 'light'?" His narration explicitly bears testimony to the fact, which William Shakespeare has immortalised in his play, The Merchant of Venice—"How far that little light throws its beams! So shines a good deed in this naughty world".

Monsur's courageous and extraordinary steps have not only brought him name and fame in his own land only, nay they have spread far and wide across the globe for the welfare of all facing difficulties. His narration depicts the varied and myriad success stories of his life. In his opinion, his election at the United Nations to the office of the United Nations Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD) was, for him, "the achievement of achievements". He recalls his discharging of responsibilities to the best of his abilities and his winning laurels both for himself and his country, particularly as a member at UNCRPD. His book bears evidence of Monsur being the first of many firsts and the initiator of innumerable associations and institutions for the welfare of the handicapped.

Janab Farid Ahmed, the publisher and his printing house, Shomoy, a 'thank you' will not suffice for the less frequently trodden path that you have taken for publishing this book. This is what makes you stand out from the crowd.

Najma Shams is a contributor.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments