Professing criticism: On Naeem Mohaiemen's new book of essays

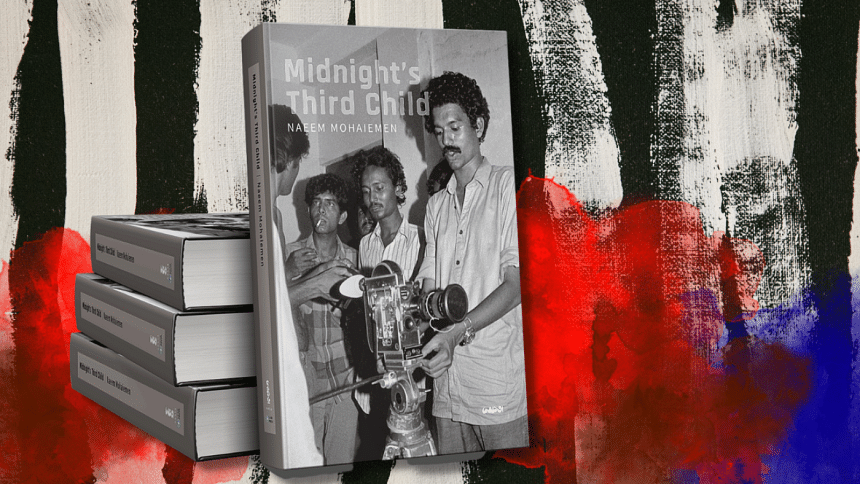

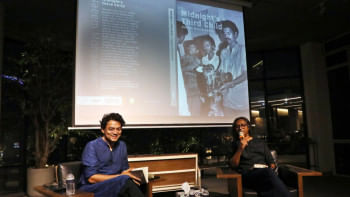

The South African critic Derek Attridge champions the term 'affirmative criticism'. It is different from scholarship, which is often, but not limited to discovering the ideological faultline of a text / artwork, measuring the silences and the text's capacity to betray itself. It is also not what pervades in much of popular media—a run-down of different factoids that are inherent and obvious to the artwork, followed by a sweeping conclusion about the writer's judgment toward the work, or in other words, a quantification of value. Affective criticism is a different approach, where the scholarship is present, but it's rooted in admiration, the critic inhabiting the role of the lover of the work. It's a difficult position, one that is close to an activist rather than a critic (at least a traditionally defined one) with the negative connotations of the noun form of the word. But it seems appropriate, a fitting part for Naaem Mohaimen, within the boundaries of his brilliant and luminous essay collection, Midnight's Third Child (Nokta, 2023).

The constellation of subjects that appear in this book are as much about many forms of art—cinema, visual art, and literature—as they are about their possible responses. To give a sense of the range of the essays, Mohaiemen writes on and about Joydeb Roaza, Chittagong Hill Tracts, Mrinal Sen, Advertising Agencies, Tareq Masud, Shahidul Alam, Pathshala, Chobi Mela, Sarker Protick, Taslima Nasreen, Rubaiyat Hossain, Dhali Al Mamoon, Zia Haider Rahman, Numair Chowdhury, and Tayeba Begum Lipi among others. Mohaiemen is an anthropologist, filmmaker, author, and Associate Professor of Visual Arts at Columbia University, New York.

In his introduction to the collection, Mohaiemen provides an account of the strange but amusing name of the book. Midnight's Third Child is a polite translation of a phrase that is frequently used by Bengalis: "Chagol'er tritiyo baccha lafay beshi" (the goat's third child jumps more). It suggests that the youngest need to strive more for sustenance. The assertion is that Bangladesh, in its long and shared history with India and Pakistan, was the last to gain independence, and its geographic and economic formations have made it such that the country needs to do more than its fair share to attract global attention. But the term is also employed as a cheeky metaphor, by riffing on Salman Rushdie's landmark postcolonial novel Midnight's Children (1981). Other than the obvious allusion, the title seems to echo a sentiment that is often attached with Rushdie's novel—the empire writes back.

This is a useful framework in thinking about Mohaiemen's chief concerns: the historiography of Bangladeshi art, the hegemonic setting and control of narrative, the formation of an inclusive canon. He delineates two ways artists and cultural workers at large have typically conducted themselves, either moving closer to the axis of power or becoming productive antagonists. The subjects in his book have occupied the latter position. Although the book is written in English, he has plenty of doubt to dispense about the language, its usefulness, acceptance, and communicability when it comes to writing and creating art in Bangladesh.

In 2019, Depart Magazine slanted its door permanently following its 22nd issue. Its sizable archive is still online, easily accessible, and its print issues can be found occasionally in Dhaka's bookstores. JAMINI, another art magazine, quite possibly has folded its cover in recent times as well. The major similarity between these two magazines, other than their premature extinction, is the language they operated in: English. "Since the English language occupies a microscopic space, what is the impetus for having two English language art journals? What is their future?" Mohaiemen asks in an essay, originally published in 2017. The answer points to a grim reality. Unlike India, where English has been embraced by people from all walks of life (a broad generalization, I am aware), in Bangladesh, English, till this date, has remained as the language of the elite, or "Bananibashi" as he sarcastically calls them in different parts of the book.

In a different essay, on a panel discussion at a group show, Mohaiemen finds himself at the center of a conversation about the proliferation of text in artworks. While he's all for it, in the works of Razib Datta he observes the use of English to express different sentiments as "awkward and inert". Later on, when he's invited to Datta's group show, he notices even more text, but this time in Bangla. While in the past the English lended an "unintended, unproductive abstraction to the work", the utilization of Bangla had been "masterful". The witty and agile use of the language seemed to him from an earlier archaic spirit, and its boundary pushing, colloquial use in lieu of the more established literary form reminded Mohaiemen of chotis (smuts) and the little magazines of the country. Yet, reading his translation of a leaflet from the exhibition, I find it to be quite the opposite of his claim.

"That day was also another, like today. Rabindranath came to Iqbal Road at the invitation of Allama Iqbal. That day too was morning. After finishing a breakfast of naan-tehari-etc, Rabindranath went for a walk. He had not yet become a tagore. He was still on his own, where today there is Calcutta Herbal, and the air is filled with Hindi songs, Rabindranath found a stray clay pitcher. It was sealed at the top. Hiding his discovery under a long cloak, itself a gift from the great Iqbal, Rabindranath took refuge in a dark corner of Iqbal Road field. After saying his Indian prayers three times, he opened the pitcher and found inside a golden frog…"

The run-on sentences, repetition of phrases, the strange time-untethered setting reminded me of the prose of Polish writer Bruno Schulz. Perhaps it's because I don't have the Bangla leaflet with me, and thus, I am not able to enter into the translation without any specific expectations. But in any case, it was far from being ineffective. The few pieces in that exhibition that had used English, Mohaiemen observed, did not retain "the frenzied energy, and density of reference". As it's clear from his own translation, it is perhaps less about the language itself—which comes off as spritely, dynamic and vital—and more about whom and how they're deploying it.

But even with his reservations, Mohaiemen remains a staunch admirer of all the works he discusses. With respect to Datta's, he goes as far as to suggest learning Bangla to enjoy the works in their full capacity. One might find this a bit inconsistent. Why is he advocating for Bangla, when he is writing in English? Maybe he is writing back to an international audience of Bangladeshi art, who, as he mentions, even now see the best of Bangladeshi art to be produced outside of it, in the diaspora. He is creating a necessary archive, establishing dialogue, much in the way of Attridge with his affirmative criticism. Sometimes, they are quite literal—the interviews with Shahidul Alam, Dhali Al Mamoon, for instance, and sometimes he achieves that obliquely—the two beautiful essays (and quite possibly the best among the ones that I have read on these works) on Babu Bangladesh and In the Light of What We Know.

He remains optimistic, open to possibilities, sometimes inserting his wishes for these works. When he writes about the socialist realism strain in documentary photography, he never denigrates the work, even though some of the popular and award winning images are made and received with the impression that they are capable of actual changes, when they clearly aren't, and to an uninformed audience, issues such as queer love and climate resilience may end up being misrepresented and cause more harm than becoming a positive catalyst. In fact, he writes with astonishing clarity, but never definitively. Each essay / interview feels like an invitation to think with him. There's a lot to be gained, just from the sheer breadth of exploration, to someone with cursory knowledge of Bangladeshi art. But for the completely uninitiated? This is a well-rounded primary education.

Minhaz Muhammad is a contributor.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments