A personal quest to explore the core essence of ‘Bengaliness’

As an academic, I find the discussions around positionality and intersectionality fascinating. I enjoy delving into questions around 'sense of self', how our identity is constructed, how language and culture shape our thoughts, learning styles and ability as well as how we interpret the world around us. These questions seem significant for my academic work around education design and developing pedagogical practices in higher education. While exploring and examining how diverse students and migrants represent their 'sense of self' in academic and social settings, I started to ponder about my 'sense of self' and how other Bengalis around me represent their Bengali identity.

I started questioning who or what is the 'Bengali', beyond our history, emotion and heightened sense of self? What defines us? What are our defining moments? What makes us who we are? Realising 'Bangaliyana' is still at the very centre of my identity even after living away from Bangladesh for more than twenty years, I started to contemplate what is 'Bangaliyana' or what lies in the core of that 'Bengaliness'. Is it just a thousand years of our shared yet turbulent history? Or is it just our intense and melodramatic emotions? Or is it just our heightened sense of self and healthy(!) ego?

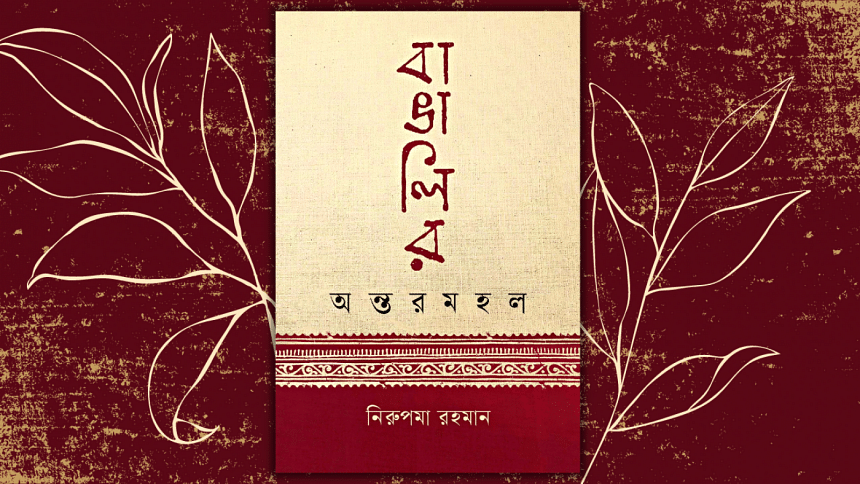

In my maiden literary work, Bangalir Ontormohol, published by Baatighar, I tried to find the answers to these and related questions. As a Bengali myself, I tried to interpret and examine the sense of 'Bengaliness' (Bangaliyana) in the 21st century context through the prism of philosophical, social, cultural, historic, linguistic, global perspectives Bengalis consciously (or unconsciously) define themselves by. In my book, I explore and explain the Bangali culture, language, community, attitudes and values in its entirety. What does it mean to be 'Bangali'? How does the actions and experiences of our ancestors inform our actions and experiences in the present? How does our language express and betray who we are? Through this book, I wanted to take my readers on a journey to explore, reflect and contemplate our identity now, and what it means for our future.

What does the title Bangalir Ontormohol mean? The word 'ontormohol' was word-smithed and evolved from the word 'ondormohol' which means intimate and personal space of the house. So, if we consider the 'Bangali' sense of self (i.e. 'Bengaliness') as a whole domain, in this book I tried to capture the intricate, intimate, enchanting and exquisite aspects of 'Bengaliness'. This book, which is a compilation of 10 essays, explores with readers the core aspects of 'Bengaliness' that we proudly term as 'Bangaliyana'. I aim to take my readers for an exploration to the intimate and personal space of 'Bengaliness' through the different chapters of this book. Hence, the word 'ondormohol' transformed to 'ontormohol' as 'ontor' meaning 'heart' keeps the concept of core essence attached to the domain of 'Bengaliness'. The title brings a greater nuance using a rather unusual Bangla word to express the concept of inner space.

To define 'Bengaliness' or who we are in the 21st century, I tried to delve deep using my own positionality and intersectionality into language, culture, history, literature, philosophy, social mores and even the gastronomic tradition of the Bengalis. Bengalis in the 21st century who are now globalised, claim to be internationalised, yet are in fact very traditional and conventional with their deep-rooted heightened sense of self. Hence, we are often confused and often mystified with our identity and positionality. It often seems time to time, we are unable to define 'who we are' and 'what makes us 'us'.

Through different chapters of the book, I used my own experiences and journey to define, explore and analyse various perspectives and aspects around what it means to be a Bengali, in terms of both the singular and the community identity. I used common jargon, proverbs and colloquial terminologies of Bangla as resources for social analysis to understand the psyche, disposition and socio-cultural inclination of the Bengalis of the 21st century. This book also talked about the Bengali diaspora and their positionality and the construct of their intersectionality in their adopted homelands. It too included the discussion around the unique aspects of globalised Bengali identity and the juxtaposition of deep-rooted Bengali identity with intersectionality of global citizenship. Using my personal anecdotes, I also showcase music as an innate component to describe and define the sense of self and intersectional identities of Bengali migrants. Bengali cuisine and delicacies being vital to any Bengali, in this book I included a chapter where the idea of 'Bengaliness' was portrayed through the enthusiasm and evolution around Bengali cuisine and gastronomy! I also dealt with the social constructs around gender and its contradictory nature around philosophical, spiritual beliefs with common social displays and actions in different chapters.

The various examples I used in each chapter to engage the reader in comprehending the sense of ever evolving 'Bengaliness' could be described as bewildering, ambiguous or enigmatic. However, all of these contradictions, confusions and inconsistencies contribute to and encapsulate the resilient spirit and eternal core essence of 'Bengaliness': Bangalir Ontormohol.

Bengalis originated from numerous races and ethnic groups, so our ancestry and pedigree are rooted to and connected to various indigeneity, cultural and ethnic traditions. Bengalis, as a race, are an aggregation of numerous races and religions, which arrived in the subcontinent for survival and conquest with a gradual accumulation of ways, wisdom and waywardness. As genetically we are more of the result of an immense mixing, plausibly that is why the Bengali psyche is full of mystery, ambiguity, contraction and disagreement. However, in all those differences within our heightened sense of self, somewhere and somehow, we are very similar. We are very chatty, talkative as a race, very argumentative and liberal, very opinionated – each of us have an opinion about everything and anything. We are conservative yet moderate often in the course of the same argument. So, if someone wants to understand the Bengali psyche, they need to understand the coexistence of opposite traits and dispositions of our character which is one of the core essences of 'Bengaliness'. We are a very 'resilient' race but interestingly enough, we don't have asingle word in our language which expresses 'resilience'. I believe that's so built into our nature that we don't even need a word to express this. We are not heroic, not even daring or valiant in our inherent nature, however, we were at the forefront of the Anti-British Movement; we are the ones who could boldly sacrifice our lives to get the right to speak in their language, we fought a whole liberation war without arms armed training and losing 3 million people to have an independent and sovereign country.

For generations, Bengalis saw and experienced numerous rulers coming from different parts of the world knowing nothing about the people of the land. Bengalis had to endure and experience the violence, tragedy and trauma of the partition and the repercussion and scar of partition is still very much alive and real in the lives of many Bengalis, generations after generations. All of these contributed to the social, cultural, emotional psyche as well as the political, ethical and intellectual practices of Bengalis.

Regardless, all such deep cross-generational experience, the Bangla language has not only been sustained but has also emerged and evolved as the core of our sense of self. To understand and comprehend the Bengalis and Bengali psyche, to get the grasp of 'Bengaliness', one needs to understand Bangla and the nuances of Bangla language. Our heightened sense of self possibly starts with our heightened pride for our language. There are so many songs, poetries written for and about Bangla praising our own language as the sweetest one. The love for our language is evident in our talkative nature that we never get to stop—we either talk, we argue, we express opinions. When we don't talk, we sing as there are songs for every occasion. From celebrating birth to bidding farewell at death, weddings or any other celebrations to movements to war – we write, we compose, we sing songs. We welcome our new year by singing, we welcome new moon for Eid by singing, and with our singing we try to entice gods and goddesses to bless us too. As we jokingly say: 'there is a poet inside every Bengali'. We are never out of expressions and opinions in one hand, on the other hand we are very romantic. And when we fall in love, we are short of our own words, we therefore take refuge in our songs and poetries to express our thoughts to beloved.

Just because we love our language, love its words, the sound of it, we love playing with words and are never short of energy of motivation to do so. Our poets and composers have written and kept writing for every possible situation. We romanticize, glorify and can glamourize even the dullest, gloomiest, most unfortunate aspects of life. We accept misery as 'God gifted destiny', we find glory in poverty, we become fearless in the most challenging times – and our poets, our composers, our bards have poetries and songs ready for us for generations to keep our calm or to guide us mentally and philosophically depending on the situation. Our chatty nature encourages us to fantasize, exaggerate, to dream of life outside the realm of reality. That's why in bangla we say satirically 'chera kathai shuye lakh takar shopno dekhi', that is: 'we can dream of millions even lying on a ragged mattress'.

We are dreamers. We never stop dreaming. And I believe that our ability to dream high and relentlessly is pivotal to our inherent resilient nature. Our dreamy nature might make us look and seem emotional and melodramatic at times. However, just because Tagore could dream of a country just for Bengalis when that was even beyond imagination, Bangabondhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman could dare to help the Bengalis to realise the dream and guide the nation to fight the liberation war. 'Bangladesh' – the country for Bengalis was born, emerged in the global map. Dreams are not always bad, are they? And not at all when that matches with a heightened sense of self and healthy ego that can bring some good.

Our dreamer nature is also connected to our intense and melodramatic emotion. We romanticize love (that is quite normal) but we fantasize parting (biroho). We feel love more deeply in detachment, from distance (bichhed). Our falling in love is also not simple or goes one direction. It encompasses different stages that are expressed with different words—purboraag, onuraag, obhishar. While 'love' and romance can be considered universal, there are some aspects of Bengali romance and love which are very much our own. The word 'obhimaan' cannot be translated in English in any way. It is not being angry or getting upset, not even being dismayed or sad or disappointed. It is all of these plus some 'Bengali' intense and dramatic emotions. Every Bengali knows the feeling and know how to handle it when their loved ones feel that obhimaan against them. But the word, the concept attached to this word is not translatable.

Language is the vehicle of cultural expression; it expresses the cultural nuances. All that we value, we think, we believe and ponder can be expressed through our language. As 'obhimaan' doesn't exist in the western concept, there is no word to express that particular emotion in English or other western languages. In the same way, the concept of 'space' or 'privacy' does not at all exist in the Bengali society or even in our psyche. We Bengalis are very much part of a collectivist society, where 'private' matters are communal, and everyone can have some opinions about 'other's business. We describe that as our own unique way of looking after each other and maintaining 'social well beings'. So, if you want to get the bangla translation of the word like 'privacy' or you want to express a sentence 'I would like to get some space' in Bangla, you'll never succeed.

As one of our poets Shongkho Ghosh reiterated, the very Bengali concept of collectivist society by saying 'ay aro bendhe bendhe thaki' that is 'let's stick together more'.Even in the 21st century,Bengalis can never encourage the concept of 'privacy'. On the other hand, there is an interesting Bengali word for the English word 'discipline'—sringkhola—which is very close and derived from the word 'sringkhol'. Interestingly, sringkhol, means to chain or shackle or restrain. Therefore, in the Bengali psyche the aspects of discipline seem like restraints. So naturally, we are always keen and thrilled even perhaps motivated not to follow any discipline.

It is remarkable that as much as we love to talk, saying 'thank you' in Bangla seems very formal and artificial. The Bangla word for thank you, dhonyobad seems very ceremonial. Bengali way of saying thanks is through our gestures, which is very much part of non-verbal expression. At times saying thanks or dhonyobad may seem inappropriate in Bengali social discourse. However, globalization makes the usage of 'thank you' more common. Even the Bengalis who are not conversant in English at all, will also use 'thank you' instead of 'dhonyobad' as this is not something we inherited from our past, rather it's the result of colonization and globalization. In the same way 'sorry' is used more than its Bengali counterpart 'dukkhito'. And on top of that our inherent inflated ego unsurprisingly impedes us from saying 'sorry' or being 'sorry'. For us this is like being defeated and/or failing. Hence, it is not surprising that saying sorry in Bangla does not get along with our 'inflated ego'. However, saying it in English might not bother us as much as it is not our own language and may mean 'nothing'.

Globalised 21st century Bengalis are now at a crossroads with their ever-growing dilemma regarding how to create a balance between keeping their heightened pride around Bangla, necessity of learning English in terms of becoming a global citizen and discounting the impact and influence of other cultural and linguistic invasion. In such a challenging time, Bengalis often lose their sense of self, get confused regarding their positionality and Bengali identity. Therefore, celebrations around language and culture at times becomes quite tokenistic, missing its focus in present and vision for future. Bangla as a language survived colonisation, partition, political aggression in the past, all of which have deeply influenced and embedded in Bangla language. Religious divide impacted the word choices in both sides of the Bengal as usage of certain words can be identified with religious belief of the user. Partition politics left its permanent scar in the language like this which in 76 years' time seems normal at the surface level, though it still has deeper sense of seclusion and separation. Bengalis are renowned for their liberal attitudes, however at times they proved to be capable of maliciously dangerous religious fundamentalism and violence.

We are full of contradictions. Bengalis have been historically ruled by others for hundreds of years, however very interestingly, we all like to consider ourselves kings in our own imaginary kingdom. We are very free spirited but always give in to the more powerful. We tend to exploit and manipulate the vulnerable one whereas we tend to succumb and capitulate very easily to the more powerful one. We can be ambitious but hesitant at the same time and that makes our logical and ethical stands a bit ambiguous and questionable. But who would question our standpoints as our magnified and overestimated sense of self is never ready to listen to any other opinions? The concept of critical thinking does not exist in general Bengali psyche. Criticism and critiquing are synonymous to us. Therefore, we are very resistant to any idea of critically evaluating. We just welcome praising, no room for appraising. But we would love to judge and criticize others. We are argumentative yet meditative, pompous even so grounded, hypocritical but wise, flippant however deep, and much, much more. All these juxtaposed traits are the core essence of 'Bengaliness'.

Another intricate aspect of our 'Bengaliness' relates to our devoutness and adoration to the word maa which means mother. For us, our ultimate admiration and dedication is set aside for 'maa' – that includes our birth mother and our birth land. From the goddess of knowledge and wisdom to the goddess of prosperity, wealth and success to the goddess of protection, strength, motherhood, destruction, and wars are all 'maa' to the Bengalis. However, when it comes to other women, we are not ready to honour them in the same way we adore and respect our mothers. Our vocabulary supplies disrespectful words which are gender specific to women. As language shapes culture, these words are the proof of our communal minds lacking appreciation and admiration for women. We do not feel comfortable when women are confident, free spirited, ambitious, and striving for better. Strong women are not feminine enough to us, striving ones are ruthless, ambitious women are greedy. This is a real contradiction when 'Durga' is goddess, not a god who is the symbol of power and strength. While we are ready to consider a god as a woman, we have not yet managed to let go of the saviour complex through which we aim to protect women – from others and themselves. We cannot even begin to imagine a woman who can protect herself, let alone having a woman as a protector.

As a woman, and more importantly, a Bengali woman, my sense of self is shaped by Bengali literature and Bengali music. Music is the source of my mental strength, philosophical view and my prism to comprehend the world around me. It sits as a core essence of my 'Bengaliness' or 'Bangaliyana'. As in Bangla music genres the text of the verse or poetry is crucial, and the melody evolves around the poetic texts and lyric induced imagery are as important as the musical composition and melodic expression. This in fact helped me to realise the aesthetics of Bengali culture and its numerous nuances, and Bengali ways of creating and expressing imagery through melody. It also makes me appreciate and recognise the migration process in a very unique way.

As a migrant Bengali and part of the Bengali diaspora I can acknowledge the unique set of challenges every migrant Bengali like any other migrant faces in terms of retaining and reinstating personal sense of self and cultural identity. Such identity is based on duality where two cultures, two languages, two types of cuisines, two different sets of societal and cultural values play vital roles. And this duality sets uniquely to every member of the Bengali diaspora. Hence diasporic 'Bengaliness' can be inauthentic to the original. Then again the question arises what is original one as this ever- evolving sense of 'Bengaliness' is always fluid and constantly changing. However, each of our diasporic identity is unique, there are some vast and visible similarities. The first sets of visibly similar changes involve word choices or vocabularies and in the kitchen. And in a way Bengali diaspora strives to get a deeper grasp of 'Bengaliness' as a survival tactic at the beginning which later becomes a more rewarding and satisfactory experience of life contributing to the healthy ego and heightened sense of self.

Bengalis are 'foodies'. Even in our dreams and imagination, we think of 'যা খুশি খাইতে পারি' (ja Khushi khaite pari) that is, whatever I want to eat (one of three blessings from ghost king in Upendrakishore Ray Chowdhury's classic'Gupi Gayen Bagha Bayen' story). When we miss our mother, we actually miss her cooking. We make occasions to feast at birth, at death, at weddings, in joy, in sorrow. We go and visit patients in the hospital with food; we visit students sitting for big exams with food, we welcome new members in the family or new neighbours in the neighbourhood with food. Our palate is ready for everything starting from bitter to sour to spicy to hot to sweet. We 'eat' solids and we also 'eat' liquid! Bengalis are fish lovers. And is there any Bengali who does not salivate in the name of pickles! However, as we deeply love sour pickles, we have a sweet tooth too. Like us, our cuisine is also an aggregation of different cooking styles and is influenced by numerous cuisines. We have a special dish khichuri for rainy days. We have varieties of pitha—dessert items—which are delicacies. Our summer afternoons make us nostalgic homemade jars of aachar on the rooftop or at the window. We have food for every occasion, every district in Bengal has particularly unique savoury and sweet items. Our core essence of 'Bengaliness' are truly connected to our gastronomic rituals and culinary traditions.

When it comes to tradition, the main realm and rhythm of 'Bengaliness' is based on the age-old vivid folklore. It relates back to our innate yet humble philosophy, the deep values and way of life which are unpretentious and modest. This reiterates the aspects of humanism, secularism and spirituality. It highlights unity and integrity of all people as well as rooted to deep mysticism. The objective of this belief is the mystical union with God who resides within the human body. Our human body is the most significant thing as the prime object of worship. God resides with us, within us – that was the main message of 'Bauls' (ancient group of wandering minstrels from Bengal who believe in simplicity in life and love) and folklore and this was the cultural way of life of the general people of Bengal for centuries. Later Tagore and Nazrul and others were greatly influenced by such deep yet simple thought. And to me that sits at the core essence of 'Bengaliness' which is to me not just a heightened sense of self, it's rather an endless quest for 'sense of self' – who we are and what makes us 'us'.

Dr Nira Rahman is an academic at the Arts Teaching Innovation in the Faculty of Arts, University of Melbourne. Her passion for her work in education, music and community inspires her to find ways to start and continue the robust discussion around diverse and intersectional identities present within the community and how that can be more inclusive. She also regularly writes for Australian and Bangladeshi (in both English and Bangla) media on various topics that connect her academic interests to her personal insights around culture, language and identity.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments