Drowning in a sea of distressed assets

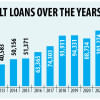

The amount of distressed assets in Bangladesh's banking sector – written-off loans, non-performing loans, and outstanding rescheduled loans, excluding loans that had been unclassified by court orders – currently stands at a staggering Tk 3.78 lakh crore, which is almost half of the country's national budget for FY2023-24. This grim reality was revealed in the recently released Financial Stability Report of the central bank, published following a demand from the IMF. While the number does not come as a surprise, given that economists and financial analysts had had doubts about the central bank's previous figures, it should nonetheless be a humbling realisation for Bangladesh Bank.

The new figure points to the gross misgovernance, nepotism, and corruption that is endemic in the banking sector. It also raises questions about the greater ecosystem surrounding bad loans and their flow, especially outside the country, and the ineffective reclaiming process.

To begin with, a basic question anyone looking at the figure would ask is, where did the money go? Judging by the economy's current state, it certainly did not go into legal local ventures. Most likely, criminal loan defaulters have laundered it abroad and/or invested in the shadow economy.

Every year, $12-15 billion is smuggled out of the country, according to Transparency International Bangladesh (TIB) Executive Director Dr Iftekharuzzaman. Moreover, there has been a sharp spike in the number of suspicious transactions in the 2021-22 fiscal year: by 62 percent year-on-year. According to the Bangladesh Financial Intelligence Unit (BFIU), suspicious transaction and suspicious activity reports increased drastically during this time. Unsurprisingly, scheduled banks filed 93 percent of the reports. To assuage concerns, BFIU suggested that suspicious transactions are not necessarily unlawful activities, but the drastic increase in such cases should be a wake-up call for any financial watchdog. In the previous fiscal year, the number of such reports stood at 5,280.

Between the banking sector being plagued by an alarming lack of governance, and day-to-day operations being heavily influenced by the banks' boards – the extension of board directors' tenure to 12 years, which was a last-minute addition to the Bank Company (Amendment) Bill, 2023, passed in the parliament on June 21 – has potentially put the sector under additional stress. Plus, the failure of the authorities to apprehend known money launderers is creating a conducive environment for financial criminals to borrow money from banks and launder them abroad.

To address the persistent problem of bad debts, the Bangladesh Bank, the government, policymakers, financial watchdogs, law enforcers, and the banks themselves will have to work in tandem to dismantle the loop that feeds the entire ecosystem, from loans being sanctioned to the money being laundered abroad or invested in illicit areas.

Apart from this, there is another problem that authorities should seriously look into: reclaiming over Tk 2.07 lakh crore that is entangled in 214,282 default loan lawsuits. It should be noted that between January and March this year, 14,650 new cases involving Tk 27,400 crore have been filed by 60 banks since they failed to recover the defaulted loans. There are 61 scheduled banks, 52 local and nine foreign, in the country, under the full control and supervision of the central bank.

In 2003, the money loan courts were established to rapidly resolve disputes centring loan repayments. But the overwhelming number of cases in comparison to limited resources are making it difficult for these courts to expedite such resolutions. And so, this money stays with the defaulters. Moreover, media reports stated that while the banks apply to lower courts to reclaim defaulted loans, the borrowers file writs with the High Court to contest rulings. At the same time, the petitioners avoid immediate repayment by securing stay orders. In addition, the eight to ten years it takes to settle a lawsuit is a great impediment to the reclaiming process.

Lending money under political or the board's pressure, circumventing due diligence before sanctioning loans, and granting loans to habitual defaulters have become regular practices. So, it is striking to see the lack of vigilance on the part of intelligence bodies and the inability of the authorities to punish known launderers. The failure of law enforcers to curb shadow-economy activities is why defaulters are confidently borrowing money with the intention of never paying back.

To address the persistent problem of bad debts, the Bangladesh Bank, the government, policymakers, financial watchdogs, law enforcers, and the banks themselves will have to work in tandem to dismantle the loop that feeds the entire ecosystem, from loans being sanctioned to the money being laundered abroad or invested in illicit areas.

Bangladesh can learn from Singapore, where the country's monetary authority is currently working on developing a secure digital platform called COSMIC (Collaborative Sharing of Money Laundering/Terrorism Financing Information and Cases). This platform will enable financial institutions to share information on suspicious customers, with the aim to minimise financial crimes, including money laundering. The Financial Services and Markets (Amendments) Bill, passed in the Singapore parliament on May 9, provides a legal framework for COSMIC.

It is high time our authorities dealt with this matter with utmost importance. They must apprehend and punish the criminals, irrespective of their corporate or political identities. The government must demonstrate a strong political will to eliminate this problem, lest the banking sector drown in a sea of distressed assets.

Tasneem Tayeb is a columnist for The Daily Star. Her X handle is @tasneem_tayeb

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments