Of lost recipes and forgotten flavours

I have always had a rather avoidant recoil to the aftermath of death. The recent but persistent presence of death and loss in my life has only made me want to skirt around and wash my hands of it more; the ordeal of having to return to someone still beloved but no longer here is not one I want to take on more than I have to. And so, I have not found it in me to visit my grandmother's grave. This August, it has been a year since I've seen her.

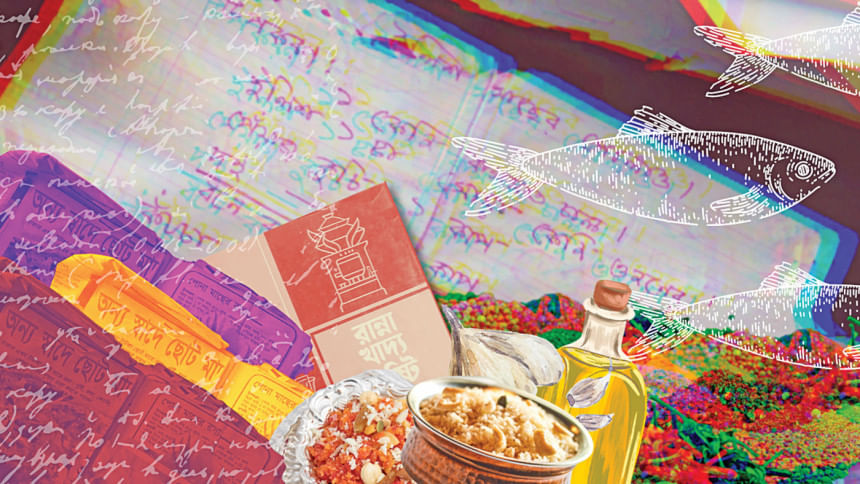

In the year between, my grandmother—her own presence once as far-reaching as the shade of a banyan tree—and her legacy of delectable, mouth-watering meals cooked in large enough batches to feed the hordes that swarmed her house, managed to make themselves known in the nooks and crannies of the homes she left behind. She was here in the last jars of kashmiri achar, or sirkar achar as she called it, and the spare bit of chaaler aata from her that my mother had stored away and forgotten about—only to later stumble upon it and use it to make ruti with the first time paya was cooked since Dadi's death. She was here, too, in her absence, in the hollow kitchen and love-blackened utensils left behind, in all the recipes I had told her to teach me but never gotten around to learning (the thought of her death still only a creeping but distant thought then), and in the dishes everyone seemed to make—the shemai and payesh and dimer halua—which never tasted quite 'right' again.

I have since lamented never finding the time to shadow her enormous cooking endeavours come every Eid or Shab-e-Barat, to note and write down her recipes because I could not afford to trust my already failing memory to remember them all—each perfected over decades of Sisyphean preparation. The few times I had mentioned it though, Dadi had been entirely dismissive of the concept, her own copy of Siddiqua Kabir's Ranna Khaddya Pushti tucked in a bookshelf somewhere, scarcely consulted and gathering dust.

My mother, always more diligent than I, had managed to collect recipes from her mother in her own scrapbook, filled with scribbled ingredient lists, short form instructions, and photos cut out from magazine and newspaper pages to accompany each recipe. And so, carefully penned on a loose leaf by Nanu's steady Bangla hand—its title distinct in residual red ink, a habit from her teaching days—the recipe for "ilish maacher polao" lies tucked between the pages of my mother's recipe book. As a sentimentalist through and through and then some, I can't help but envy my mother for what she has been able to preserve of my Nanu that I haven't for Dadi. The last jars of sirkar achar threaten to deplete each day.

For all my lamentations, it is not merely grief that sustains cookbooks, but stories of resilience, joy, community, and shared history. Although it has now become somewhat of a joke that recipe blogs will have a novel's worth of backstory preceding the recipe part of the, well, recipe, the food memoir has emerged as a popular means of truly putting oneself on the plate. The introduction of the personal in the form of such food memoirs begets the political dimension of food, memory, and history, although one might argue that recipe books without explicitly documented histories are still quite personal and therefore political by virtue of their existence and being handed down the family lineage.

In Cookbook Politics (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020), political theorist Kennan Ferguson examines such dimensions and political functions of the recipe book as they pertain to community-building and collectivity, culture and ethnicity, ideology, national and international boundaries, and more. In Tori Latham's Bon Appétit article "Why Is Every Cookbook a Memoir Now?", Ferguson is mentioned as saying that "the desire to connect has always been central to cookbooks…[having first become] necessary in cultures where family members moved away from one another and could no longer pass down recipes or techniques as easily."

Lately, as I contemplate whether it is truly in my best interest to leave home and settle abroad as everyone says, I think most about my people, and then about food. It takes a lot for me to not look at my well-wishers like a kicked puppy, indignant but still hoping they would say something, anything different—that it was alright for me to stay back, that I did not have to be condemned to such exile.

I have often been a staunch critic of Jhumpa Lahiri's The Namesake (Mariner, 2003)—a consequence, no doubt, of having to analyse it to death during my A Levels—and in particular Lahiri's opening description of Ashima Ganguli tossing up jhalmuri for herself during her pregnancy but finding that there was always "something missing". It was such a tired take on the immigrant experience, so cliche and overdone and melodramatic and…and now, I find myself in her position, wondering how it would possibly feel to step out of the house and not find a jhalmuriwala a few feet away. Now, I feel as if I know what it is to have "something missing", be it in all the food that my grandmother won't cook anymore or in the thought of having to concoct my own jhalmuri overseas with an ingredient list that goes, "Rice Krispies and Planters peanuts and chopped red onion," and wishing "there were mustard oil to pour into the mix."

There is always more to say about the politics of food and its sociocultural implications—the micro and macro-aggressions aimed at the fragrance of spice, the joyous use of hands, the hegemonic overpowering of Bangladesh's cuisine with Indian labels. There is more still to say about the joy and pleasure of food, as Isabel Allende investigates and delights in, for instance, in Aphrodite: A Memoir of the Senses (first published 1896)—the crossings of food and carnal pleasure, "the boundaries between love and appetite", and the histories of aphrodisiacs and love-philtres.

But for the time being, we circle back to love, and grief. I find myself thinking of my friend who has just landed in Bangladesh from the UK, and how his first story on Instagram upon returning home has been that of a table spread of food. Food made at home, with love and a sense of responsibility, no matter how Sisyphean and mindless its preparation.

I think of the love sustained in the jars of sirkar achar.

When I mentioned to someone I loved about how they were her last jars of sirka as I was serving it to them, they had told me to keep it for myself, to savour it, to make sure it lasted longer. If I were to hoard every little thing Dadi had left us, it would all begin to rot; how could I let any of it go? But it goes down easier as I watch people I love come to know Dadi, through what she left us because she can't be here herself. Even if it means there is less and less of her for me to hold on to.

I know, because I knew my Dadi, that the achaar is sweeter shared. I only wish I had found the time to write down how to prepare it.

Amreeta Lethe is a Sub editor at Star Books and Literature and the Editor-in-Chief at The Dhaka Apologue. Find them @lethean._ on Instagram.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments