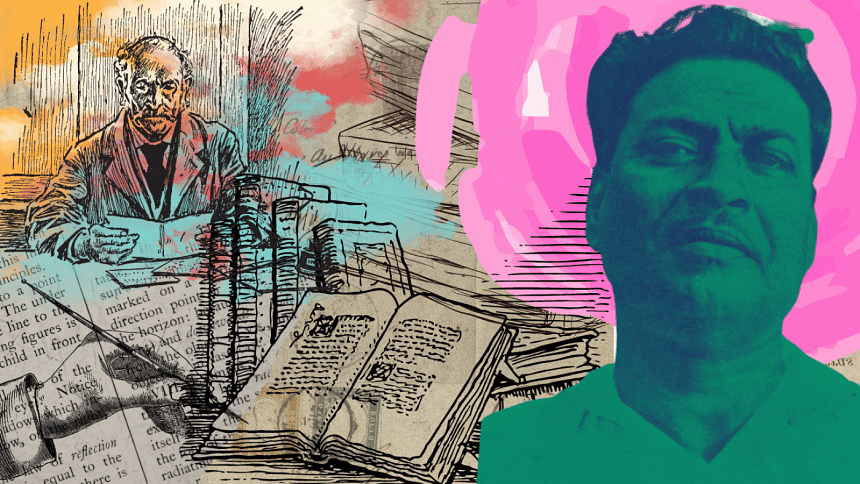

The Writer

It was a Sunday. I had just had my lunch and was getting ready for a nap when someone called from outside. "Is Sitanathbabu at home?"

Now who could come at this time of a Sunday afternoon?

I asked my son to bring the visitor in as I was reluctant in getting up. A little later, a lean young fellow with glasses followed my son to my bedroom. He greeted me respectfully and asked, "And you must be Sitanathbabu?"

"Yes, and where are you from?"

"I've come to see you. You were seated at that doctor's chamber this morning when my elder brother and I were going for a bath. My brother said that you're a writer. I was soaked in oil and hence did not greet you. But I heard that you came here for the weekend only and would live later in the day. And hence, I've come to meet you now."

"I knew a little of the younger writers, but I had no idea who Ramchandra Sarkar was. But the boy seemed so enthusiastic that I didn't want to hurt him. It was obvious that he had not come across such an audience in a while."

I was not too happy to hear the reason behind his visit. He meant to ask for a write-up, I was sure. As far as I knew, there was no newspaper in that rural area. Were they planning to bring out something?

The lad appeared to be very humble and slowly took a seat. But I noticed that he did not take his eyes off my face even once. He kept on staring at me through his glasses. At length he said, "I have something to ask of you, if you don't mind."

I urged him to say what he wanted.

"Will you teach me how to write? I passed B.A. in Bengali this year and I teach at the local school. My brother is the sub-registrar here. It's my wish to become a writer. I've brought some of my writing with me; would you like to take a look?"

I agreed and he drew out a workbook and handed it to me gingerly. "I wrote these when I was still a college student. There are a few short stories, a few poems and songs here."

He looked at me earnestly and I said, "Not bad. The songs are quite good."

The young man bent forward in excitement and eagerness. "You like them? What about the stories? Do you see any promise there?"

Refusing to comment directly, I said, "The premises are good. You're still young; you'll learn."

He was carried away in joy. "I've always wanted to be a writer, you know. Everybody at home scolds me because I chose Bengali at college. My cousins hold good positions, and they know English well. They wrote to my brother asking me to forget Bengali while there is still time. Nobody at home is happy about my literary endeavours. I am the youngest in my family. My brothers want to see my writing, but they say that all of it is a waste of time."

I could not find fault with them for thinking this way.

The young man continued with his tale: "I got the job here right on the day my results were published. I roam around by myself throughout the day. There's not a single person here with whom I can hold a decent conversation. Nobody knows anything about literature. Such a backward place! When I heard of you, I thought you might advise me on writing. That's why I came. I've been so frustrated that I've not written anything in the past one year."

He tried to convince me that he was not like everybody else. He was well-versed in Tagore, Saratchandra, Ibsen, Shaw, Tolstoy, the up-and-coming writers, and Vaishnav poetry.

"Among the young writers, what's your opinion of Ramchandra Sarkar?" he asked.

I knew a little of the younger writers, but I had no idea who Ramchandra Sarkar was. But the boy seemed so enthusiastic that I didn't want to hurt him. It was obvious that he had not come across such an audience in a while.

So, I tried to pacify him by giving an imaginary account of Ramchandra Sarkar. He listened to me with deference and said, "You are just right. Do you know what I think? According to Ibsen…" and he went on talking about Ibsen, Maeterlinck, Tagore and many others. He quoted them frequently and tried to present some arguments of his own. It seemed that he was really pleased with himself, and he was trying to understand what I thought of his capacity for argument, knowledge, and intellect.

I asked, "How much do you get paid here?"

"29 taka. It's okay for now as I live with my elder brother. But if he relocates, it will become a problem. I have to contribute to the family."

"But your other brothers are there, right?"

"They are not my real brothers, but cousins on my father's side. My father is blind, and I have a younger sister who is yet to be married. We all live in the same house, but my cousin brothers eat separately. "

He continued, "I have had this dream since childhood that my writing will be published in newspapers. When I saw the books of famous writers, I dreamt of publishing such books myself. I had a class-friend called Kanti Basu. I met him in Kolkata this past winter. He showed that one of his short stories had been published in Bharatbarsha. And I thought, how come they are writing and publishing? So many people will get to hear about them!"

He stared out of the window and looked at the sky wistfully. Then he went sad as he said, "But nothing came out of me."

I was impressed with his earnestness and eagerness. He was a different kind, and probably eccentric too. As he went on talking, I kept on noticing the different emotions playing on his face—eagerness, apprehension, reverence, hopefulness, and sadness. He was not like all the other people I meet in everyday life. Those faces are carved in stones, showing very little emotion. I tried to encourage him, "I'm sure you will write better in the future. You've already shown promise. You're still young and your entire life lies ahead of you. I believe that someday you'll become an excellent writer and we'll derive a lot of pleasure from your work."

He looked up at me shily with a smile. Then he said, "What are you saying? You'll derive pleasure from my work?... Do you really think that something will come out of me?"

"Why not? If you keep on trying, I'm sure you'll do great."

"Kanti Basu is my friend and of my age. He has already made a name for himself. How long does it take to become famous? And what does it take?"

I realised that my afternoon nap had gone through the window. Well, what could be done? I had envisioned that I would be able to get rid of this fellow with a few words. But this one kept on talking and now he was thinking of fame. However, I felt pity for him, and I continued to answer his questions. "There's no hard and fast rule to that", I said. "After you've written some good pieces, you start to make a name for yourself. If the readers are happy with your writing, fame comes easily."

He kept quiet for some time. Then he said cheerfully, "I'd been wanting to talk to a writer for a long time. I once went to meet Debabrata Mukherjee in Kolkata when his Aparinata made quite a stir. I stayed awake through the night and finished the book. I loved it so much that I thought I would write a novel like that one. I even wrote about eight to 10 chapters. I showed it to Kanti who said that it read like Debabrata Mukherjee's novel. That's a problem I have—whenever I like a book, I take up the style and plot. Anyway, Debabrata Mukherjee was very busy that day and hence I couldn't meet him."

To encourage him, I read through one of his songs again. He stared at me with a big smile on his face. He listened to my praises about the song, and it seemed that for the first time in his life he was getting some appreciation for his writing. As we were talking, he glanced around the room and said, "I've never sat so close to a writer. And nobody ever spoke to me for such a long time."

After another 20 minutes, he wrapped up rather unwillingly. Perhaps he thought that I would be irritated if he stayed too long.

On his way out, he returned again and asked falteringly, "I don't know how to say this. I don't know what you'll think. If I give you 10 taka per month, will you teach me how to write?"

I felt sorry for the poor fellow. He was ready to give me 10 taka from his monthly salary of 29! His wish to become a writer was so ardent that he was willing to run his family with only 19 taka.

I said that he would not have to pay me anything. He could visit me when I came on holidays. If I could be of service, I would do it gladly. He prostrated before me in respect and left with his workbook in high spirits. Then he turned around to look at me through the window and asked again, "So, you think I can do it?"

"I'm sure it will happen", I assured him. "But you have to keep on practising."

May the Almighty forgive me for this falsehood. How could I tell him on his face that I could not find anything in his writing, or that his story and poetry were really bad? There was nothing worth saving in his writing either. But if prevarication makes people happy, so be it. What is the point of throwing such awful truth on one's face?

Sohana Manzoor teaches English at the University of Liberal Arts Bangladesh.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments