“We need writers to know what society will look like in the future”

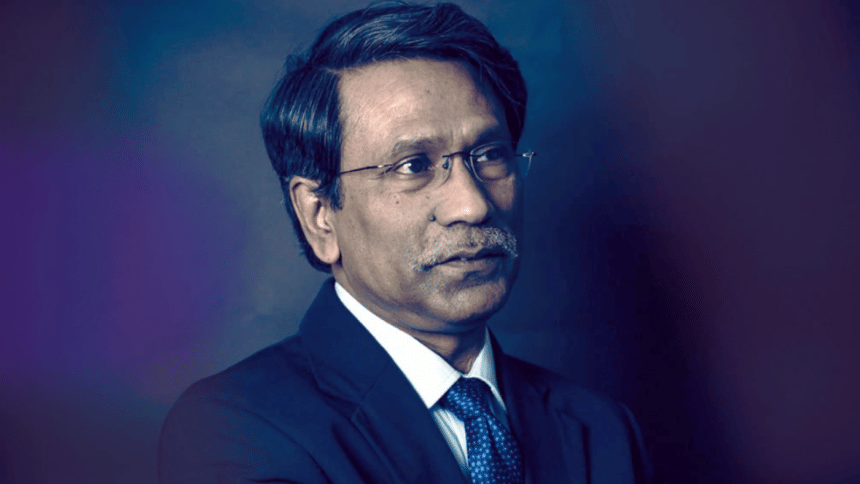

Ali Riaz, distinguished professor of politics and government at Illinois State University, non-resident senior fellow of the Atlantic Council and president of the American Institute of Bangladesh Studies, was born in Dhaka and now lives in the United States. He completed his graduation and post-graduation from the Department of Mass Communication and Journalism of University of Dhaka. He later received a Master's degree from the University of Hawaii in the United States. In 1993, he received his Ph.D. degree in political science from the same university, researching civil military relations in Bangladesh.

Some of Ali Riaz's notable books are Culture of Fear, Missing Democracy, The Crisis of the Ruling Class of Bangladesh, and Unity in the Democratic Movement. He writes regular columns for newspapers on political and social issues at home and abroad. Recently, Emran Mahfuz of The Daily Star spoke to him about various issues like the role of the country's intellectuals, the constitution of Bangladesh, freedom and journalism.

You mentioned at some point that only a few intellectuals of this time discuss the pathways of authoritarianism. If so, in whose eyes do we see the future of the country?

It is the primary responsibility of a sociologist is to identify the trajectory of authoritarianism. Politicians will join them in this endeavour. That doesn't mean it's not an author's job. Writers do that as well; they have done that in the past and will continue to do so. It is also the job of those involved in journalism. If someone asks if anyone in Bangladesh is doing this now, I'd say some people do. They are only a few; many don't. I am rather concerned that the critical approach towards sociological studies in Bangladesh has not been developed strongly. It is true that critical thinking has limited space in the state, politics, and society, and one of the reasons for this is the education system. Our education system encourages imitation, does not teach us to ask questions. Institutions of higher education are not independent. Independent research institutes have not emerged, so as a result, the critical trend is not getting stronger. Otherwise, it would have been easier to find a way forward.

It turns out that timeless literary works have been written overcoming fear. But writers in Bangladesh are now subject to a form of self-imposed censorship at the outset. What does this indicate?

There are many reasons why literary pieces have become classics. Conquering fear is one of them. However, in today's Bangladesh, the reason why you see a writer is timid is because a culture of fear has been created in the society. It is a result of prolonged authoritarianism.

This culture of fear is the product of politics, and it is also the task of politics to deal with it. A large number of contemporary writers in the country think of avoiding politics. But that itself is also a kind of politics—the politics of the status quo. Authoritarianism is being prolonged, fear is being prolonged. While some of them are still talking and writing about the fear, but not too many; the biggest indication is that they are not thinking about the future. As individuals, as part of society, as writers, we need to think about what this society will look like in the future. I see little desire to push that consideration. Most writers are busy with their own lives.

There is a lot of debate around 'art for art, or art for life'? What's your take on this?

I can't agree with the idea that art is for art's sake, because regardless of the form of art, it is a representation of real life. The question is not about whether that's of today's or yesterday's or that of tomorrow's. What we imagine is limited by our experience. As a result, art is talking about life itself. Our experiences are not created alone, it is also influenced and shaped by our surroundings, by the people around us, and by society. Everyone's experience is different, and art is about expressing those different experiences. So, for me, art and life are inseparable.

This year you edited a collection, Lunthito Bhobisshot (Plundered Future), about the state's crisis. Through whom do you see hope?

In the collection, my fellow writers and I have tried to explain the depth of the economic crisis of the country. The crisis is caused by politics, because of crony capitalism. And this crony capitalism has been created as a result of lack of accountability. The solution is to create an accountable regime. If an accountable system is not created, the situation will get worse. In that sense, I have faith in the citizens, who are constantly being crushed by the pressure of this system. They will surely say, "Why can't we ask questions to those in power?' or "Where is my share in wealth?"

Many people follow your writing and thoughts. Do you think your observations would have been keener, stronger if you were closer to the events?

I'm grateful to those who follow my works.. What is not easily seen can be grasped at some level. However, it is true that at any time when an individual is closer to the events taking place in the country, it is easier to understand the pulse of life there. But there's also a downside to it: it puts them at risk of becoming a part of the incident—what is called 'being immersed.' That way, there is no chance of seeing it from a distance.

Again, with the technological advancements, is there a way to stay too far away from these events? However, because I live far away, I am deprived of sharing these experiences with everyone. I try to overcome the limitations that result from the distance.

How do you think the printed book is under threat in the online, e-book era?

Every new technology brings challenges to the old ones; some survive, some don't. E-books and online books are posing challenges to print versions, for both fiction and non-fiction genres, but I don't think they will altogether replace the print version. It is too early to write the obituary of print books.

This interview has been translated from Bangla by DS Books and abridged for relevance.

Emran Mahfuz is a poet, writer and researcher.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments