Special treatment for AL is the new norm

The Awami League is set to hold a public rally in Rajshahi on January 29. Party leaders and activists have been taking preparations to ensure that it will be a mammoth one. As the national election is just a year away, such public rallies will basically turn into election campaign rallies. So, aspiring candidates will try to get as many bodies as possible on the streets to reflect the range of their strength and support.

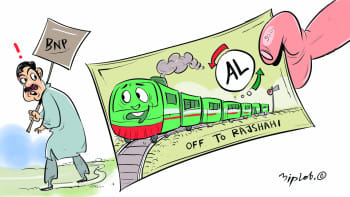

In all of this, one piece of news caught my eye. A special train is set to take Awami League leaders and activists to Rajshahi from Natore to attend the rally on January 29. State Minister for Information and Communication Technology, Zunaid Ahmed Palak, told journalists that the special train will not affect the schedule of regular trains. He also said that the AL men would pay for the ride.

But another report stated that AL lawmaker Habibe Millat Munna of Sirajganj has rented a special train of 15 coaches for the Rajshahi rally.

Can a political party – regardless of whether they are in power or in opposition – use public property to attend a party rally? And is this option available to any citizen, for any political party?

In September last year, the main opposition camp, BNP, announced divisional rallies protesting the killing of BNP men, hike of electricity and fuel prices, and to demand the release of party leader Khaleda Zia. Almost all their rallies were obstructed by the ruling party, directly and indirectly. The same thing happened when the BNP held its rally in Rajshahi. A transport strike was "called" across the entire division on the morning of December 1. Rajshahi city was practically cut off from the rest of the country.

At the time, ruling party leaders and ministers said that transport owners and workers had enforced strikes and that they had nothing to do with them. But we also witnessed the transport strike being withdrawn soon after the BNP rally ended. We also found that mobile internet services were disrupted around the venue on the day. We saw how BNP activists were obstructed and, perhaps more importantly, how the general people suffered as a consequence.

As a journalist, I covered some of the BNP rallies and found the same narrative to be true. I saw how a single-day rally turned into a three-day rally. For the BNP, there were transport strikes so that its supporters and sympathisers could not join. For the Awami League, there were arrangements of special trains so that party faithfuls could join the rally in droves.

Our political culture has taken such a turn that we take for granted that the ruling party will get some special treatment when they hold rallies, and the opposition is bound to face obstruction for doing the same. What happened centring on BNP's rallies is actually normal and, it appears, so is what's about to happen on January 29 in Rajshahi (that is, the special train for Awami League's rally).

This new normal is currently the most pressing problem in Bangladeshi politics. We used to hear the phrase "level playing field," but when the caretaker government system was abolished following a court order, opposition parties and many civil society members said there wouldn't be a level playing field anymore. And a free and fair election would not be possible if a level playing field is not ensured. But ever since the 2014 election, the term "level playing field" appears to have evaporated from our political vocabulary, speeches, discussions, and even from rhetoric. That is the new normal.

As distrust, fuelled by intolerance, widens among the two major political camps, and the path towards mutual understanding is basically shunned, this new normal will push the whole nation into an abyss of political uncertainty that is far from normal.

Mohammad Al-Masum Molla is deputy chief reporter at The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments