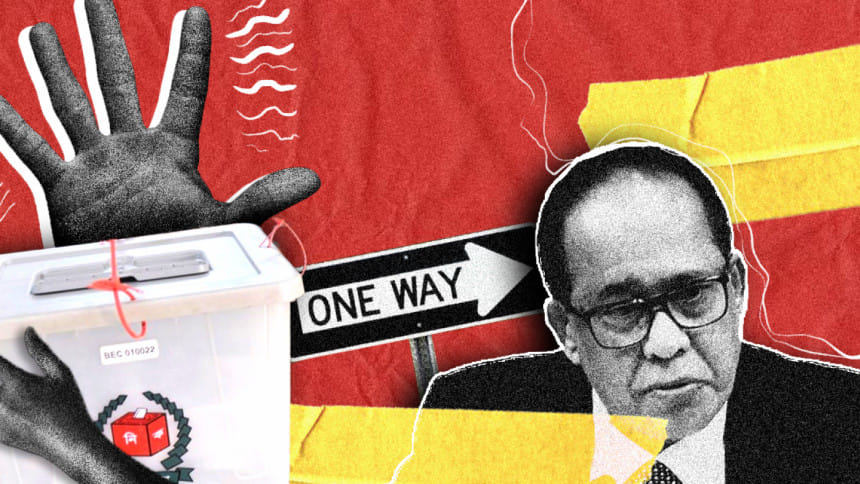

We are heading towards another one-sided election

On November 15, Chief Election Commissioner (CEC) Habibul Awal declared the schedule for the 12th parliamentary election, to be held on January 7, 2024. As scores of cases have been filed since October 28 and most of the BNP leaders are now either in jail or hiding, it is almost certain that the coming election will again be one-sided. The situation at the moment is fraught with serious concerns.

The first concern is that a one-sided election, without the participation of the main opposition and other major parties, may not even qualify as an election from the legal point of view. According to Black's Law Dictionary—used by legal professionals—election means the exercise of a choice, the act of choosing from several alternatives. If there is no choice, there is no election. However, the choice will have to be credible, and the people must be free and have fair opportunity to choose through voting. As Mahmudul Islam, in his book Constitutional Law of Bangladesh, argues, our "Constitution does not envisage anything else than free and fair election… (Pg 973)."

Let's use an example to clarify the issue of choice. The option of drinking a glass of tap water and a glass of mineral water does not offer a legitimate choice, as a rational person will not "elect" to have the tap water. The outcome here is predictable and, in a sense, predetermined. However, an option between a glass of mineral water and a glass of boiled water will offer a legitimate choice—as both are worthy candidates.

Likewise, in the real-life electoral arena, if voters are given the freedom to choose between candidates of Awami League and Trinamool BNP, or any other fringe party for that matter—not the real BNP—they are likely to reject Trinamool BNP, as they are not credible alternatives. Thus, if BNP, the main opposition party, does not participate, there will be a sham election on January 7. In absence of a "genuine election"—a term used in Article 21(3) of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights—the Election Commission (EC) will fail to meet its constitutional obligation to hold a free, fair and credible election.

The second concern relates to the environment for holding a free and fair election. On October 25, the CEC himself acknowledged that the appropriate environment for an election was absent. Then the violence of October 28 occurred, leading to the police filing many cases, implicating thousands of BNP activists and arresting almost all its leaders, which completely tilted the playing field in favour of the ruling party. In this situation, most, if not all, potential BNP candidates will not be able to file nomination papers by November 30, even if they decide to participate in the upcoming election.

Yet, the EC declared the election schedule, ignoring the tilted electoral field, paving the way for a one-sided election and ensuring the continuation of the ruling party being in power. The highly partisan bureaucracy and law enforcement agencies will ensure that outcome. Again, with such an election, the Awal commission will not be able to meet its constitutional obligation to hold a free and fair election under Article 119(1)(b) of our constitution. Incidentally, it is surprising that the EC is totally mum about the cases and arrests, even though under Article 126, the executive authorities are to assist the Election Commission in discharging its functions.

Let's use an example to clarify the issue of choice. The option of drinking a glass of tap water and a glass of mineral water does not offer a legitimate choice, as a rational person will not "elect" to have the tap water. The outcome here is predictable and, in a sense, predetermined. However, an option between a glass of mineral water and a glass of boiled water will offer a legitimate choice—as both are worthy candidates.

Thirdly, without the participation of BNP and other major political parties, the legitimacy crisis of the present regime will persist. As we are aware, in 2014, there was a one-sided election, in which 153 MPs were "elected" without the voters casting a single vote. The 2018 election, although participatory, was fraudulent, manifested by stuffing of ballot boxes the night before. A TIB study found electoral irregularities, like stamping ballot papers the night before and ballot box stuffing by capturing booths on election day, in 47 out of 50 constituencies surveyed. An analysis of the centre-wise election results obtained from the EC through an RTI application by SHUJAN found that 100 percent votes were cast in 213 polling centres under 103 constituencies, and 100 percent votes were cast to a single symbol in 587 polling centres under 75 constituencies. In addition, BNP received zero votes in 1,177 centres, Jatiya Party received zero votes in 3,388 centres, and even Awami League received zero votes in two centres, indicating that they were all cooked up numbers. These two controversial elections created a credibility crisis for the ruling party.

The fourth concern is about the Awal commission itself. Section 4(1) of The Chief Election Commissioner and Other Election Commissioner Appointment Act, 2022 mandates the Search Committee to search for qualified candidates from the nominations made specifically by political parties and professional bodies for appointment to the EC. However, the Search Committee formed on February 5, 2022, allowed individuals to nominate names, including their own, in violation of the law. As a result, the Awal commission was appointed based on nominations of individuals who were not legally authorised to nominate. For example, late Dr Zafrullah Chowdhury publicly announced that he nominated Awal for the position of CEC, although he was not legally eligible to do so. Thus, the declaration of the Awal commission is bound to have questionable legality.

To conclude, the upcoming one-sided election cannot be called an election in the legal sense, as there would not be any legitimate choice in absence of BNP's participation, and such an election will not help the EC meet its constitutional obligation to hold a free, fair and credible election. Since the Awal commission is appointed in violation of the law, the schedule it declared is questionable. Thus, the next election will not fulfil our constitutional commitment to a democratic Bangladesh; rather it will lead us, as a nation, to uncharted waters.

Dr Badiul Alam Majumdar is secretary of SHUJAN: Citizens for Good Governance.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments