Italicisation policing, penning with a colonised mind

My friend was advised to italicise all the foreign words in her poems.

This advice came from a well-meaning woman

with NZ poetry on her business card

and an English accent in her mouth.

I have been thinking about this advice.

The publishing convention of italicising words from other languages

clarifies that some words are imported:

it ensures readers can tell the difference between a foreign language

and the language of home.

I have been thinking about this advice.

Marking the foreign words is also a kindness:

Every potential reader is reassured

that although obviously you're expected to understand the rest of the text,

it's fine to consult a dictionary or native speaker for help with the italics.

I have been thinking about this advice…

– Alice Te Punga Somarville, How to Write while Colonised

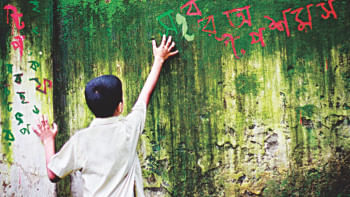

Like many bilingual writers, the world leaps from many places for me; one exists where thought is birthed and forged, another where thought becomes utterance and text. So, I'm thinking in Bangla, but I'm penning the thoughts in English. Often, I find myself between a rock and a hard place while writing/using words (as it is) that we grow up with but are not English. Should we italicise the words our mother and grandmothers raised us with? If these words are foreign, the question then is: to whom, though? As readers, writers and learners, isn't it our humble responsibility to cross the boundary of literal translations and find joy in learning?

We, the Bangladeshi South Asians who were once a part of the Indian subcontinent, learnt English as part of a colonial legacy and education. This colonial legacy, however, couldn't erase a lot of native terms we learnt from our ancestors, many of whom came from peasant backgrounds. Bhaat, bhorta, ruti, etc are now gaining acknowledgment in the international culinary arena, but with the nudge of italicisation. Often, this reappropriation of native terms is implied with slanting words: italics.

Writer and poet Khairani Barokka and essayist Madhushree Ghosh asked a question, which I myself often ask: how normalised is italicising words of our own languages, that it takes us years, if not decades to unlearn?

Native terms from a "foreign" language are the words that are not used in the dominant culture, and the supposed "ethos" of using italicisation is to highlight them and keep the cultural "purity." When a foreign word—one that isn't part of the language in which the text is being written—is highlighted in italics in a work of literature, it becomes "other." Etymologically, it still belongs to the sentence; but if you can think beyond grammar, you will understand how it has been set apart, singled out, left to fend for itself. When you are reading a passage with italicised words, you cannot help but stumble over; you stop, look at it again because it stands out. You perceive it as something alien—something out of the usual. Then you dive back into the safe waters of the familiar, eyes gliding over the page, devouring the words that haven't been italicised. Maybe unintentionally, but the notion of Us vs Them crystallises, becomes the standard. Even if the aim is to highlight the uniqueness of the word or signpost it so the reader won't trip over it, such italicisation also implies how hard we try to pass or pass through. Passing is what you have to do because or when your legitimacy is in question. If the word is Other, then it does not belong.

When you are reading a passage with italicised words, you cannot help but stumble over; you stop, look at it again because it stands out. You perceive it as something alien—something out of the usual. Then you dive back into the safe waters of the familiar, eyes gliding over the page, devouring the words that haven't been italicised. Maybe unintentionally, but the notion of Us vs Them crystallises, becomes the standard.

This process also renders a distance between the italicised and unitalicised that doesn't necessarily elevate the former—that, in fact, emphasises the importance of the unitalicised to the dominant language in use (I always prefer Bhaat-Maach-Bhorta, over pizza or spaghetti, see?). I've come to understand the practice of italicising such words as a form of linguistic gatekeeping—a demarcation between which words are "exotic" or "not found in the English language," and those that have a rightful place in the text: the non-italicised. Such slanted truth very tactfully pushes you to the "other" box. If you are a person who has eaten bhaat-bhorta millions of times in your life, this aspect of your life will be othered. And subconsciously, if you are one of those people and are italicising bhaat-bhorta, you are othering yourself, your own life, in language.

In the case of us Bangladeshis, there is an extra layer in the gatekeeping process. So many of us say masala, instead of moshla; saree instead of sharee; roti instead of ruti (when you open a word document and type these words, you will notice that red lines show up only under the latter words; ever wondered why?). Thanks to colonisation, there is a large South Asian population that speaks English, there are many South Asian migrants in English-speaking countries, where curry is a pub staple and ethnic apparel is in vogue, hence "masala" and "saree" being unitalicised and made grammatically correct. However, we the successors of a "peasant" society are left behind with our "peasant" language which never made it to the realm of unitalicised dictionary. Now, the question is: did we try though?

Every colonised people, in whose soul an inferiority complex has been created by the death and burial of its local cultural originality, always attempts subconsciously to elevate above his/her peasant status at any cost. And sometimes the cost is by agreeing to be alienated in the name of "standing out" just to feel included.

Understanding decolonisation from the linguistic lens and italicisation policing might be hard to grasp for some people, but if you really think about it, you will understand. Feminist scholar Sara Ahmed said we can dislodge a lodge by showing how we are lodged, how we are sealed into the object or thing, not subject, not human, not universal.

In this month of celebrating Bangla language, let's embrace what our ancestors taught us. Let's embrace our native tongue in its true sense; let's unapologetically own the terms sharee, ruti, bhorta, to name a few, even when we are writing them in English (let's practise writing them without italicisation). They might not look/sound trendy, but that's what we are; they represent us and our eons-old culture. Let's embrace our true self.

S Arzooman Chowdhury is MPhil student at the University of Cambridge.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments