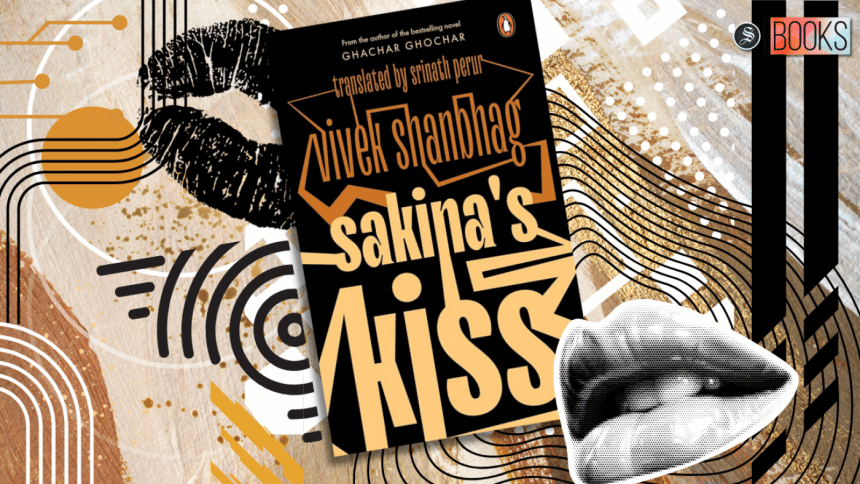

Unseen chains of consequences

Vivek Shanbhag's comedies often instil a dread in their reader, a thrilling concern for his characters and their supposedly inevitable ruin. The Kannada novelist and playwright is a master of contemporary story-telling, and no matter the anxieties his prose causes for the reader, it is worth the experience. In his 2017 novella, Ghachar Ghochar (Penguin Books), which shot him into international acclaim, this dread was directed at the narrator's wife Anita against the backdrop of her cruelly aspirant in-laws. The briefness of the story was crucial to its singular, explosive end.

In his latest, Sakina's Kiss, he sets off on a different route. The joint-family enterprise in Ghachar Ghochar is replaced with a tenuous nuclear family, but the emotional hold his characters possess on the story have quadrupled. Greater in length, though still under 200 pages, Sakina's Kiss is better able to portray the insecurities and haplessness of middle-class life. The narrator, Venkat, introduces his family as: "To put it simply, if you averaged out various aspects of the lives of lakhs of people like ourselves, you might as well be describing us." Yet in no other work has the perilous middle been more pointedly felt. Reading the novel, one is aptly reminded of John Updike's famous words: "It is in middles that extremes clash, where ambiguity restlessly rules."

00000000The Indian middle-class, however, is a pitiful breed in Shanbhag's novel, for whom the pursuit of happiness is solely a route of confidence upward the corporate ladder.

Venkat and his wife Viji, fans of self-improvement, obsess over self-help titles, which unpretentiously populate Shanbhag's stories the same way literary works are often nauseatingly name-dropped in novels of the new-wave variety. Shanbhag, too aware of the dull trends of the novel, satirises this romanticisation of an awareness of literature (the author would aptly call it "out-knowledge") with comic aplomb.

When a few boys arrive at the couple's flat to seek out their college-going daughter, Rekha, the parents are thrown into a whirlwind of adventure. Over the course of the book, we find that Venkat and Viji are actually quite terrible as parents, unable to exert any form of authority or respect over their teenager. Attempting to make sense of their shortcomings, Venkat complains: "When your child begins to rebel at home, they turn into hot ghee in the mouth—too good to spit out, too painful to swallow."

Their dilemma forces the otherwise self-professing liberal-minded Venkat to say, "I found the idea of handing over her responsibility to a husband strangely comforting." As father and daughter clash over patriarchy and politics, the reader is given a glimpse of how obnoxious fatherhood can get. Venkat's father, along with his uncle, had gone further ahead and stolen land from his mother's family, an act of betrayal that still haunts Venkat and provides a sense of foreboding in the background of all their actions.

What makes Sakina's Kiss so impressive is how local and upfront it feels. Even the bus journey Venkat and Viji take to their village smells convincingly South Asian: "That the most patient bus driver cannot resist the temptation of an empty road ahead is a truth well-known to anyone who has occupied the last row in a bus."

Srinath Perur's translation into English, as was his previous attempt with Ghachar Ghochar, has made Sakina's Kiss an immensely enjoyable and stirring read. Venkat's miserable hesitations, his clueless demeanour, and his loneliness as a father makes him an unforgettable character. Near the end of the novel, when Venkat says, "The intensity of a life can be measured in stupid decisions," one comes away resolute that Shanbhag's brilliance here was to make Venkat unable to decide. He cannot confront his family and he cannot face up to reality. He is completely a servant of coincidences.

Sakina's Kiss is certainly among the best novels to come out in 2023, if not the very best. Shanbhag continues to be an original writer of fiction in a sea of knock-off prose-stylists.

Shahriar Shaams has written for Dhaka Tribune, The Business Standard, and The Daily Star. He is nonfiction editor at Clinch, a martial-arts themed literary journal. Find him on X: @shahriarshaams.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments