Why recognising unpaid care work is important

On April 23, 2023, Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, in an Executive Committee of the National Economic Council (ECNEC) meeting, instructed the Planning Commission to find a way to include the work that women perform within the household, commonly referred to as "unpaid care work," into the calculation of the GDP. This instruction speaks of her commitment towards gender equality and appreciation towards the contribution of women for their labour, irrespective of whether they get paid or not.

What is unpaid care work? It is the work that women perform at home, behind closed doors, which remains mostly unseen and invisible. Their work is considered household work, something that women are "supposed to be doing." However, this work is productive as well as reproductive, and critical to the wellbeing of the family and society. Apart from taking care of children and the elderly, cooking, cleaning, washing, and fetching water, women are involved in economically productive activities such as looking after poultry, livestock, preservation of seeds, and other agricultural work.

The primary reason to recognise this work comes from the concept of "dignity of labour," and for families to realise the importance of this work and accord it the respect that it deserves. Women, by and large, are responsible for the health, hygiene, food security and over all wellbeing of the family. Making their work visible and giving it formal recognition will raise their status as families will become aware of their contribution, and there is hope that it will result in reduction of discrimination, domestic violence, and early marriage. There is a possibility that formal recognition will have an impact in elevating women's position in the family.

The progress of women in Bangladesh is a well-recognised fact today. Thousands of women have attained a level of social, political and economic empowerment. However, not being a homogenous group, this progress has not benefited all women equally. Differences in class, ethnicity, education, income and physical features has determined their level of empowerment. Although our aspiration is to have all women get an education, acquire skills, and become part of the labour force, the reality is that millions of married rural women will not seek jobs outside their homes. They will work within their households and carry out unpaid care work, or at best get involved in home-based enterprise.

For years, economists have argued that unpaid care work cannot be included in the GDP as it is out of the System of National Accounts (SNA), because their product is not in the "market." Remaining out of the SNA means such contribution remains economically invisible. However, advocates for recognition of unpaid care work have launched campaigns and research which has resulted in a number of positive initiatives from government and NGOs.

A number of important studies related to unpaid care work have been carried out in the last few years. Manusher Jonno Foundation commissioned the Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD) in 2013 to undertake a study titled "Evaluation of Women's Work" with a sample size of 13,000 women. The study revealed that on average, a female member of a household undertakes 12.1 non-SNA activities, the corresponding figure is only 2.7 for a male member. However, the most stunning finding of the study was that if women's unpaid work were to be monetised, it would amount to 2.5 or 2.9 times higher than the income of women received from paid services. For example, if a woman received remuneration of Tk 5,000 per month for her work in a garments factory, the corresponding amount for a woman's unpaid work, if monetised, would be around Tk 15,000.

The Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics carried out a Time-Use Survey with support from UN Women to gather evidence of women's work. The survey revealed that women on average spend seven times more time on care work than men. It also revealed that women use about 25 percent of their daily time on unpaid care work including cooking, cleaning, washing, and taking care of children and the elderly, etc. On the contrary, their male counterparts only spend 3.3 percent of their daily time on such tasks. It was also found that the workload of women increases by over 151 percent with marriage, but for men, the percentage is 78 percent.

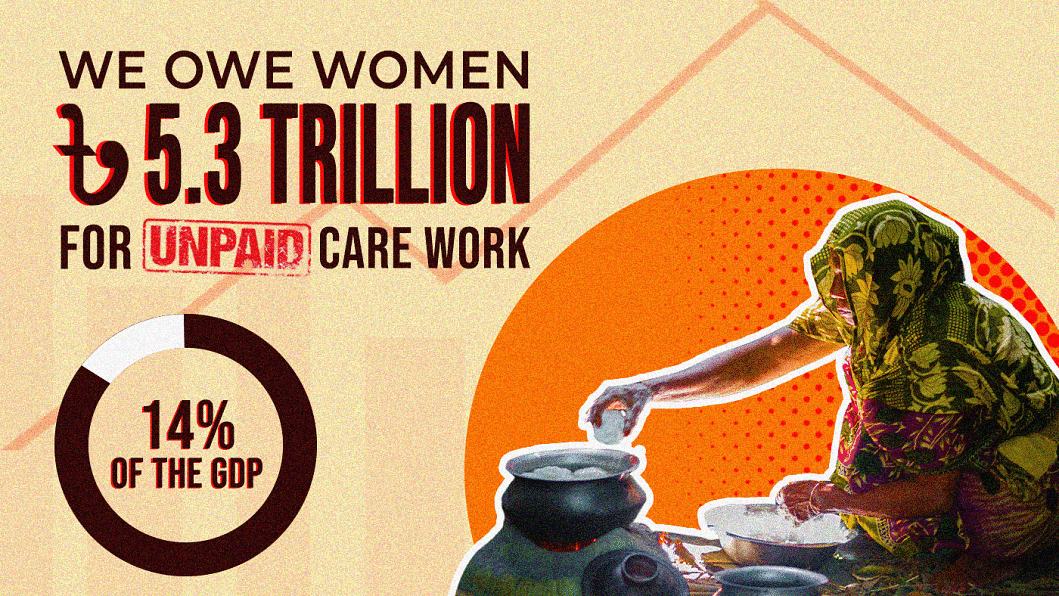

A more recent study conducted by Bangladesh Institute of Development Studies (BIDS) reveals that women's unpaid care work, if calculated, was worth Tk 5.3 trillion, which is equivalent to almost 15 percent of the GDP. According to the study, women get only 1.2 hours for paid employment while men get 6.1 hours.

Researchers argue that as long as care work is not accorded the importance and dignity it deserves, "care crisis" will continue as it remains firmly in the "informal" economy. Feminist economists have long argued that productive work that is not accounted for in Systems of National Accounts, nor as part of the GDP of a country, is invisible work.

Evidence from studies above and across the globe shows how gendered care work still is. As per research conducted by Oxfam International in 2020, women carry out 76.2 percent of global unpaid care work, dedicating 3.2 times the hours that men do, totalling 12.5 billion hours every day. The researchers estimated that the annual monetary value of women's unpaid care at a conservative $10.8 trillion, which is three times of what Microsoft, the world's biggest company, is worth.

Valuation of care work is necessary to give recognition to the contributions of family caregivers. It also provides means to compare the private contributions of family caregivers with public expenditures on care, and the ways in which contributions are counted and valued. Additionally, it demonstrates how unequal these contributions are. It makes family care work visible and brings to light the inequality in men's work compared to women's work.

Given the evidence we now have, there should be no obstacle to take concrete steps towards formal recognition of unpaid care work and its inclusion in the GDP. Researchers have come up with a formula using the replacement method to evaluate and count its monetary value. The Satellite Accounts System has been used in a number of countries across the world successfully as a parallel GDP. This will bring to public and private attention the contribution of women to the family and society and create a positive image about them.

Development plans of government must include care work as an integral part of the care economy and allocate resources accordingly. Gender Responsive Budgeting is a positive step towards women's economic empowerment. However, much more policy support is required to reduce women's care work burden to give them options and choices for decent employment or to be homemakers. The 4 R's commonly used by advocates—Reduce, Recognise, Redistribute and Reward—is a pathway towards women's social and economic empowerment.

It is time to make women's work in all its dimensions visible, valued and accorded the respect it deserves.

Shaheen Anam is the executive director of Manusher Jonno Foundation.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments