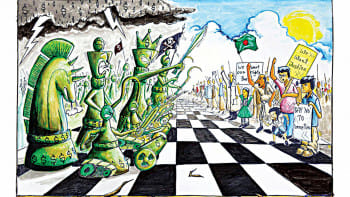

Has poverty-alleviation spending made any difference?

One critical question raised in the context of poverty alleviation in Bangladesh is whether poverty reduction spendings have made any dent on poverty in the country. Sometimes, we generalise the responses to this question. Sometimes, the responses are based more on rhetoric, rather than hard facts. And sometimes, the responses are partial, rather than comprehensive. But an objective response to the question requires an understanding of the dynamics of poverty in Bangladesh, the nature of poverty alleviation spendings. It requires familiarity with poverty and inequality data, and a sense of the magnitude of the poverty alleviation expenditures.

Poverty in Bangladesh has many dimensions. At one level, it can be structural, rooted in the structure of the economy. It can also be transient, which has more of a seasonal nature. Thus, people can be permanently trapped in poverty, or they can get in and out of the poverty trap, depending on the seasonality of the economic outcome. The sources of impoverishment may also vary, ranging from socio-economic shocks (for example, recession or Covid-19) to environmental degradation, giving rise to the environmental poor. Poverty can be absolute, or relative, which is nothing other than inequality. And inequalities occur not only in income, but also in non-income dimensions. Furthermore, inequalities are not always explained in terms of outcomes like educational achievements, but also in opportunities such as access to health services.

Looking at the poverty alleviating expenditures, there are two dimensions to them—poverty impacting expenditures and targeted expenditures for poverty alleviation. The first set of expenditures are not exclusively directed to poverty alleviation, rather they impact poverty through various channels. Thus, expenditures on social services like health, education, and access to clean drinking water help reduce impoverishment. In societies where poverty is significantly wide-spread, poverty reducing strategies at the macro and sectoral levels are essential. In fact, in such instances, macroeconomic policies must be geared towards poverty reducing measures—expenditures which indirectly impact poverty work through channels like economic growth, employment generation, and expansion of social services, etc. Yet, even with such policies, a significant number of people will remain outside of the macroeconomic policy net. And those people will need direct targeted poverty reducing interventions. Extreme poor, people with disabilities, people who live on ecologically fragile lands need targeted interventions, such as social protection.

A careful review of the poverty data of Bangladesh clearly indicates that over the years, the incidence of poverty has come down significantly. The 2022 Household Income and Expenditure Survey, published by the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics puts the income poverty rate in Bangladesh at 19 percent, down from 58 percent in 1990—down by more than two-thirds. The extreme poverty in the country stands at about 6 percent. There is no doubt that these are impressive achievements.

But the same thing cannot be said about relative poverty, or inequality. In fact, the income Gini-coefficient (the economic measure of inequality) of Bangladesh is alarmingly high—it was 0.50 in 2022. In theory, the value of the Gini-coefficient ranges between 0 to 1. Higher values within the range indicate higher inequality. A Gini-coefficient value close to 0.5 would mean high inequality. Inequality is also manifested in Bangladesh in other non-income dimensions. For example, in the area of child malnutrition, while 38 percent of the children in the poorest households are stunted, the comparable figure for the richest households is 20 percent.

Over the years, more than half of the public expenditures in Bangladesh was directed towards poverty alleviation. For example, in the fiscal year of 2020-21, 55 percent of the public expenditures were allocated for poverty alleviation. The figure has gone up to 58 percent in the fiscal year of 2024-25. In the intermittent years, the figure stood at more than 55 percent. However, direct expenditures for poverty alleviation show a declining trend—in the fiscal year of 2020-21, more than four-fifths of the public expenditures on poverty alleviation were allocated towards directly fighting poverty. In the fiscal year of 2024-25, the relevant share has come down to two-thirds.

In the context of all these figures, the two relevant observations are that firstly, even though a correlation is not easy to establish between the huge amounts of resources going to poverty reduction in Bangladesh and its impressive achievements in poverty reduction, a possibility of a strong association between the two cannot be overruled. In fact, a significant part of the poverty reduction has to be accounted for by the public expenditures on poverty alleviation. However, the issue is how the allocated public resources to poverty reduction can be made more efficient and effective. Secondly, a declining share of direct expenditures on poverty reduction make the poorest and the most marginalised people more vulnerable. What can be done about it?

In order to make public expenditures on poverty reduction more efficient, macroeconomic and sectoral poverty reduction programmes and projects should be formulated with a concrete focus. A sensible implementation plan with an achievable timeline will safeguard against resource leakages. The effectiveness of such programmes and projects in alleviating poverty can also be enhanced if they are solidly anchored in Bangladesh's overall development plans aligned with its overall goals and objectives, and if the macroeconomic framework and sectoral policies are poverty-sensitive. Linking poverty alleviating measures with employment generation, social services, and pro-poor economic growth would make public resources for poverty reduction more effective.

Protection of the ultra-poor and the marginalised groups require increasing resources for direct expenditures for poverty reduction, not reducing them. It would require intensifying various existing social protection measures and exploring new innovative mechanisms. The need for all these measures has become even more important given that Bangladesh faces high inflation and there can be more external and internal shocks. The second phase of the National Social Security Strategy can be solidified. The Rural Employment Opportunities for Pubic Assets Programme (REOPA) can also be an effective instrument for poverty reduction among the poorest and the marginalised groups.

Dr Selim Jahan is the former director of UNDP's Human Development Report Office at UNDP in New York.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments