In both form and content: A political (un)reality

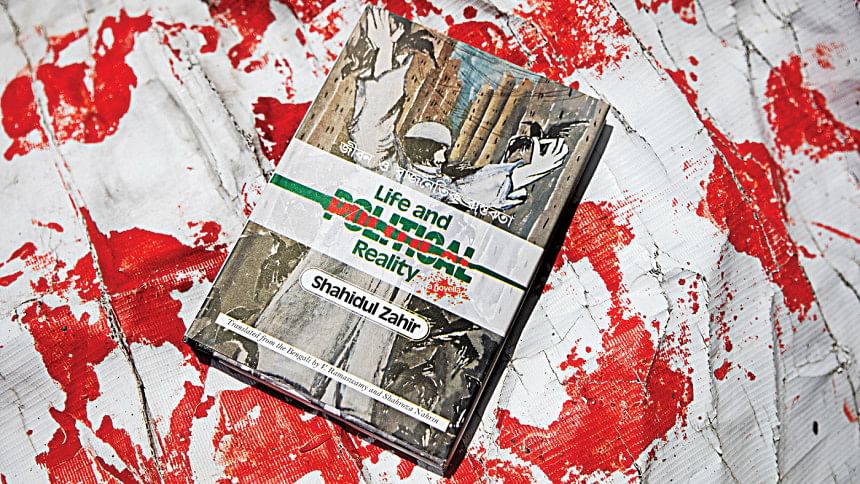

Over the last two semesters, my course on South Asian writing at both the undergraduate and graduate level begins with Shahidul Zahir's Jibon O Rajnoitik Bastobata (Life and Political Reality, translated by V Ramaswamy and Shahroza Nahreen). As anyone who has ever had to design syllabi for survey courses—courses that survey a period, a genre, or an entire body of work representing various peoples, languages, and political history—knows, a lot of complex thinking goes into the process. Issues of representation, language, length, complexity, diversity, readability, and even pleasure haunt an educator's thinking as he finalises the texts for the semester. As I spent the last week away from my classroom, and as the nation erupted all around us revisiting old, foundational questions about what it means to be a patriot and indeed, a Bangladeshi, I recalled the discussions we had on 1971 in my classroom, especially while reading Zahir together.

Published in 1988, Shahidul Zahir's first novella is a tale of two days, set 15 years apart and written in one long, breathless paragraph, examining 1971 and its aftermath. The story is centered primarily around Abdul Mojid, a young man from Dhaka's old parts and his affective ties with his traumatic past and grotesque present. The slim novella opens with the sound of Abdul Majid's sandal's straps going "phot", a mundane sound that is magnified by its significance as he hears the voice of Moulana Bodu's son Abul Khair address the inhabitants of his moholla or neighborhood as "brothers". Bodu, an accessory to the Pakistani forces during the terrible nine months of 1971, was the man behind the rape and murder of Mojid's sister, Momena. The novella's opening is breathtaking—Zahir draws the reader in with unparalleled urgency and plunges those that have only heard of 1971 anecdotally from family members, or read about dispassionately in mandatory school textbooks, straight into the narrative.

I was particularly enraptured by Life and Political Reality's usage of the device of memory—both individual and collective—and how it helps construct the narrative of the war and its consequences. Memory is a silenced device in the novella, particularly the memories that address gendered and sexual violence. Memory is also unreliable and open to distortion and damage.

At an allegorical level, Life and Political Reality is about Bangladesh itself and the inexorable ways in which a small community in Dhaka's Lakshmibazar bears witness to the nation's history. While Bodu's 1971 actions of violence and his later rehabilitation form the central narrative tension of the novella, it is Mojid's final decision to sell his ancestral home that stages the ultimate rupture in the narrative—with Mojid abandoning his home, the nation too, snaps, mimicking the muted explosion of the sandal's snap, but this time on a much grander scale.

Often a restrained, poignant study of the inequalities of life experienced by the ordinary subjects of the state, Zahir's fiction almost always captures the haunting of Bangladesh's political past with an urgency that is hard to ignore. A bureaucrat by profession, Zahir is generally considered to be one of the most influential and unique voices to have emerged in independent Bangladesh's literary landscape.

I was particularly enraptured by Life and Political Reality's usage of the device of memory—both individual and collective—and how it helps construct the narrative of the war and its consequences. Memory is a silenced device in the novella, particularly the memories that address gendered and sexual violence. Memory is also unreliable and open to distortion and damage. Rituparna Mukherjee notes that characters like Bodu "alter the memory narrative to suit their own needs". Yet some memories linger. After Khayer addresses the moholla as brothers, and upon realising that the horrors of the past are acutely, profoundly present in the current moment, a devastated Mojid sobs into his wife's shoulder. As he touches her bony shoulder and remembers the exact spot where Momena was pierced by a bayonet, Mojid bears witness to the trauma of a nation's collective gendered and sexual past while also confronting his own limitations as a masculine subject of a liberated state. Feeling weak and emasculated by the reappearance and reclamation of power by the forces that made those nine months a traumatic experience for oppressed subjects such as himself and his sister, Mojid's devastation is made palpable with agonising clarity.

Memory further uncovers the link between communal (dis)harmony and the West Pakistani regime's commitment to rid the "Hinduani" from the East and marking them as minoritised, Hindu-ised Muslims whose lives are expendable. Mojid's memory recalls how Momena is the only Muslim girl in the Lakshmibazar area who sings in a choir with the Christian Bashanti Gomes, establishing a moment of quiet communal camaraderie. That the singing leads to Bodu cursing Momena out and an ontological enmity being formed between the teenage Mojid and Bodu reestablishes Zahir's flair for marrying the personal with the political. As the current unrest continues to unfold with dizzying speed all around us, I wonder how our memory will recall this July. How this story will be written. What conversations we will have about it.

Much has been said by critics about Zahir's writing, its uniqueness, and its carefully chaotic, breathless brilliance. Hasan Azizul Huq argues that there is "extreme disinterestedness" in Zahir's "narration or writing style…severing the roots of emotionality, waving logic aside, taking unexpected turns, creating unanticipated relations through the threads of sentences". For Sarker Hasan Al Zayed however, that disinterestedness Huq speaks of is revealed in the "form of sudden interjections and subtle innuendoes" in the text. "It is, as if, partial exposure is the mode through which this novel has chosen to explore the truly traumatic memories and political failures of the nation," he adds. The collective narratorial voice and the specificities of the lived realities of characters give the novel a poetic joie de vivre. In the days prior to the pogrom of March 25, for instance, when Jamir Baypari and Abdul Majid's mother show up to Bodu's house and Bodu slaps Jamir Baypari, the moholla's collective audience "looked on in a dazed astonishment, like how entranced spectators gaze at a magician's inexplicable acts and try to figure it out". This collective inability to comprehend the meanings of such action signifies the inexplicable violence of '71, as well as testifies to the incomprehensibility of genocidal violence at large. Ironic then, that a similar sense of incomprehensibility haunts a lot of our collective thinking now, especially as we too, look on in "dazed astonishment" as events continue to unravel around us.

Finally, it is not only the urban underclass human who testifies to the trauma of the past but the nonhuman other that participates in narrating the unsayable in the novella. From the crows that eat the flesh of the enemy, to the Tulsi tree that bears witness to communal harmony as well as antagonism—the ecology opposes as well as reproduces the regime of terror set in motion during and after the war. When Bodu's young son Abul Bashar (a hermaphrodite who dies under mysterious circumstances) is permitted to mourn the death of his beloved dog but the moholla is unable to mourn their seven dead neighbors during '71, the text stages a collapsing of the binaries separating the human from its nonhuman other and with it, raises complex questions about the quality of life as well as death under conditions of extreme political unrest.

Last semester, as our course drew to its conclusion, a student mentioned how this is now the book she makes everyone read—her parents, her friends, her peers. For generation Z, 1971 is more relevant than ever, as evidenced by this July. Throughout this slim novella, Zahir helps sketch the unadorned horror of the return and rehabilitation of noted war criminals as political leaders, problematises the forgiveness granted to those perpetrators by former leaders of the liberation movement, and examines Mojid's relationship with his memories, his neighborhood, and eventually the nation. If there's one thing our troubled political history has taught us, it is that our literature has steadfastly engaged with the complexities and nuances of our political landscape and today, if we are to step away from the binarism of us vs. them, Zahir's work can be our guiding light.

A version of this article first appeared in The Literary Encyclopedia, February 2024.

Dr Nazia Manzoor teaches English at North South University. She is also Editor, Star Books and Literature.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments