Beneath the headlines: Readings from a citizens’ perceptions survey

Recently, BRAC Institute of Governance and Development (BIGD) presented the findings from a nationally representative Rapid Research Response 2024 survey to get a national picture of citizens' perceptions, experiences, and expectations in the first 40 days since the fall of the former autocratic government on August 5. This survey is part of a longitudinal survey that BIGD has been conducting since 2019. The current round was a phone survey that collected responses from 2,363 adult men and women from all districts. District and rural-urban population weight was used to calculate national-level estimates.

The findings attracted widespread attention on traditional and social media. In this write-up, I want to go beneath the headline, offer a snapshot of the average mood of the nation, and examine trends and variations which can hold important insights for political and policy strategy.

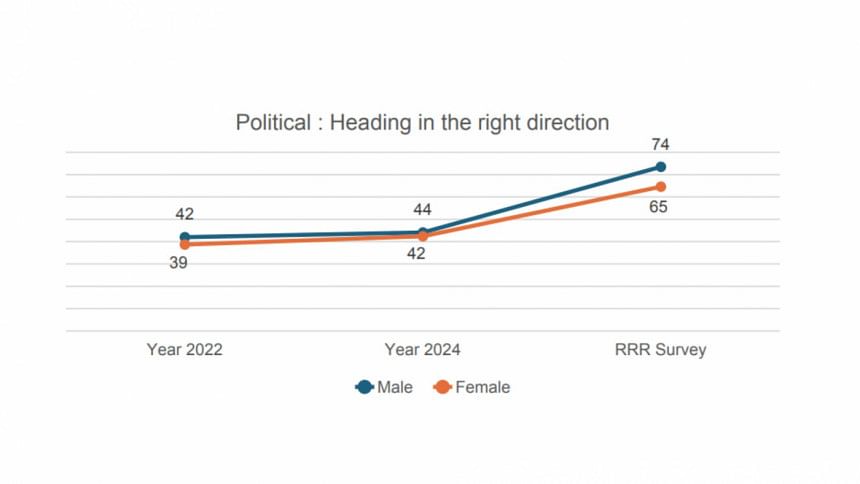

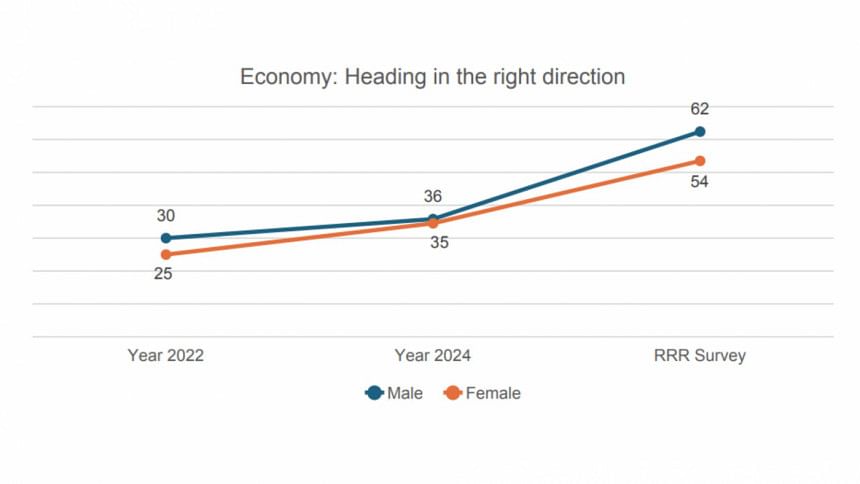

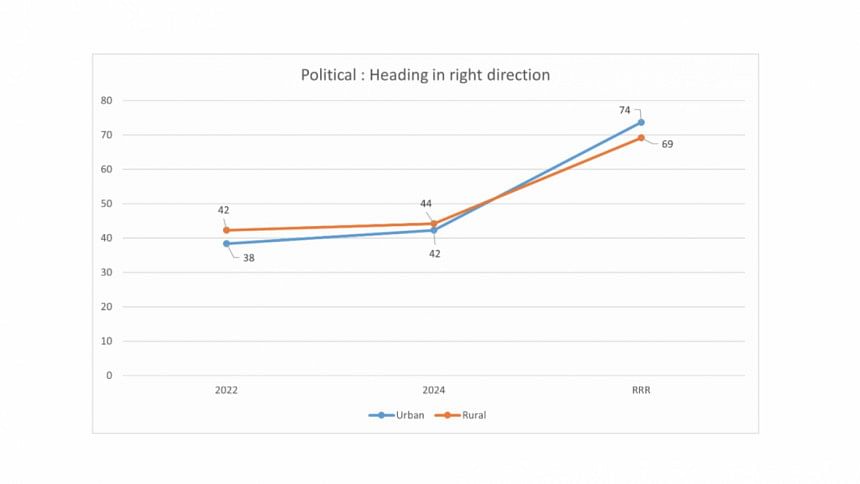

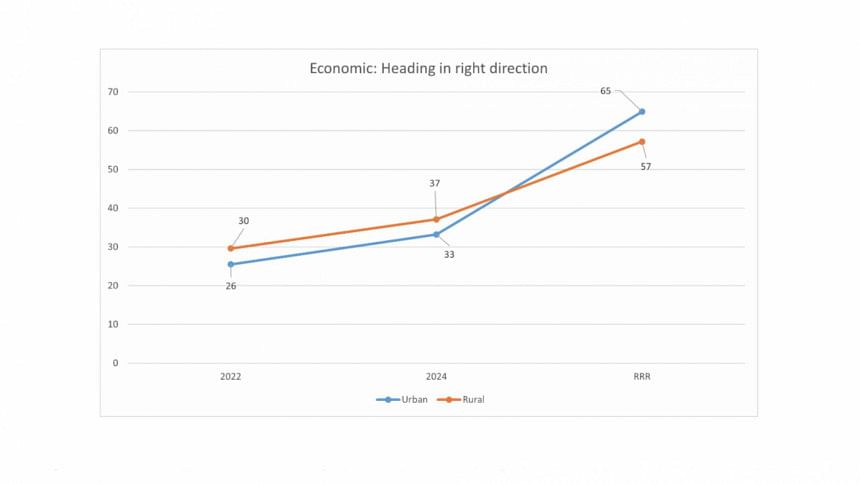

The general findings on the national mood were, to an extent, as expected—people feel very optimistic, both in terms of the political and economic directions of the country. There was a dramatic improvement from similar surveys we conducted before, the most recent one being in January this year. The mood upswing from the 2022 survey to the latest RRR 2024 survey is from 39 percent to 71 percent for political direction and from 25 percent to 60 percent during the same period for economic direction. The optimism is driven by a sense of freedom and relief, which creates aspirations about a better future. It is also a reflection of the urgency with which people want to see tangible positive outcomes and progress.

Looking at the trend data across 2022, January 2024, and the RRR 2024 survey, we notice that the optimism in the political direction (39 percent, 41 percent, and 71 percent for each of the three surveys) is consistently higher than the corresponding economic direction (25 percent, 32 percent, and 60 percent) of the country. In short, economic optimism remains markedly lower than political optimism, remaining behind by about 10 points in each of the surveys. Furthermore, in the RRR 2024 survey, we find that the economy has also been clearly prioritised as a focal area of reform. Indeed, there is a real urgency to get the economy to work for the majority in terms of creating jobs, improving real wages, and managing inflation to reduce the sufferings of people in the context of the ongoing polycrisis since the pandemic.

Digging deeper into these numbers, we find three interesting differences in trends occurring across lines of gender, income, and rural-urban areas. Women have consistently been less optimistic than men across economic and political directions, and the gender gap seems to have grown further in the RRR 2024 survey. In the economic direction, the gap was five percentage points in the 2022 survey, and grew to eight percentage points in the RRR 2024 survey. Similarly, in the political direction, the gap widened in the same timeframe from three percent to nine percent. Despite the strong presence of women in the revolution in July, their representation in post-August 5 decision making spaces has been less visible. There have also been growing incidents where the future of women's rights seems uncertain and under assault. These developments and experiences may have played a role in shaping women's perceptions and expectations.

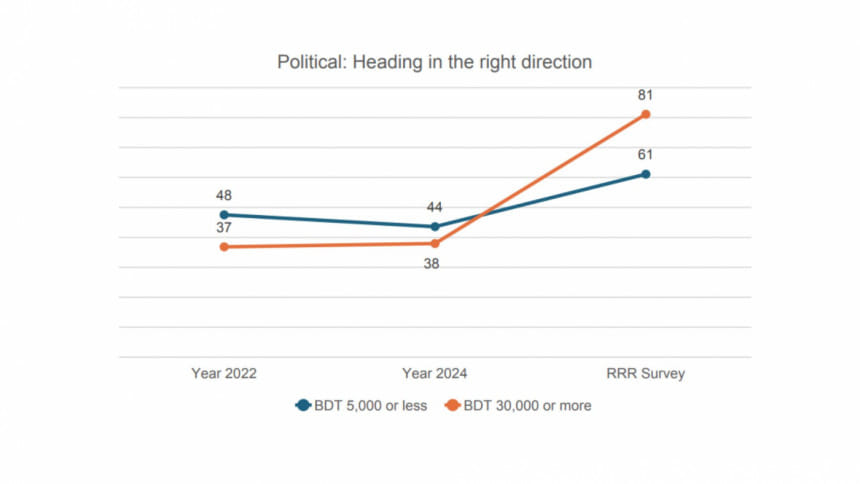

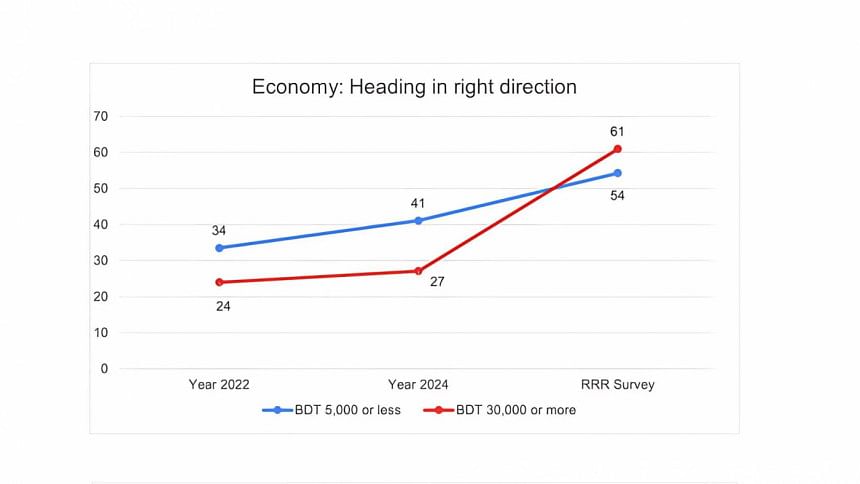

When it comes to the income disparity within the sample, a reversal is happening. In the 2022 and January 2024 surveys, poorer people were more optimistic, both in terms of the political and economic direction of the country. Those with a monthly family income less than Tk 5,000 were about 10 percentage points more optimistic in economic and political direction compared to those who had a monthly family income of more than Tk 30,000 in the 2022 survey. In the RRR 2024 survey, those with a monthly family income of more than Tk 30,000 were 20 percentage points more optimistic than those with monthly family income less than Tk 5,000 when it came to political direction, but the reversed gap was much narrower (only five percentage points) when it came to optimism related to economic direction.

It is the better-off in the sample, ie mostly the middle class, who have had a steep rise in their optimism resulting in the reversal. This may perhaps be a result of the socioeconomic demographic relating more to the uprising, especially politically. Nevertheless, it has implications for the future political and policy strategies.

We find similar reversals in both political and economic optimism between rural and urban areas—people in rural areas were more optimistic than the urban population in the previous survey rounds; this reversed in the recent RRR 2024 survey. In the 2022 survey, people in the rural area were four percentage points more optimistic in both political and economic directions of the country compared to the urban sample. Comparatively, in the RRR 2024 survey it was the opposite, with the urban population now five percentage points more optimistic than the rural population in terms of political direction and eight percentage points more optimistic in terms of economic direction. This change of trend in optimism and aspirations in the urban population, in the context of urban poverty and employment reality, may increase different types of claims given that urban labour is relatively more organised. The reversal against rural areas also needs political and policy attention. In addition, political and policy attention is needed for the comparatively lower optimism seen in the rural areas.

It may be challenging for opinion surveys such as this one to reflect true public opinion, especially on topics about which people may be afraid or embarrassed to express their views or preferences publicly. In this RRR 2024 survey, we used an experimental method called a randomised list experiment to identify biased responses to questions where we thought such bias was likely. One such question was if the respondent supported the one-point demand of the uprising calling for the resignation of Sheikh Hasina on what was being called July 34. We find that an overwhelming 83 percent of the respondents said yes to the question. The randomised list experiment suggests that the true, unbiased yes was 60 percent, suggesting that 23 percent of those who said yes did not give an unbiased response.

This type of self-censorship raises an important challenge for the democratic Bangladesh we all want to craft where everyone can express their views without fear. The July uprising has opened up this freedom in ways that were unimaginable over the last 15 years. Still, the divisive wounds will need to be healed through restorative justice so that we can become more united and inclusive in our diversities, paving the way towards people's deliberative democracy.

Imran Matin is executive director at BIGD, Brac University.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments