Utpal Dutt and the new dawn

I notice the first theatre season in the new Bangladesh Commonwealth has been marked by a revival of Utpal Dutt's play about corruption among the social elites, Hari Phatibe. This brings back memories. My own first introduction to East Bengal was seeing a production of Utpal's Titash Ekti Nadir Nam at the Minerva Theatre in Kolkata in 1963.

As we sat around the jutting apron stage, fisherfolk came at us from all sides. It was spectacular, quite literally breathtaking. We were in East Bengal. Illusion, of course, as all theatre is but, if we are lucky enough, we can choose our illusions. It was palpable that Bengali theatre was undergoing a lively transition, experiencing a new dawn.

Arriving in the city just in time for Kali Puja, I found myself, a 24-year-old "firingi" drama student, interviewing Utpal Dutt for the BBC. Don't ask me why me any more than why only last month on the cricket field of–irony of ironies–Churchill College in Cambridge I was talking about Utpal and the exciting mid-60s theatre renaissance with a Bengali bowler named Banerjee.

With the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare's birth coming up in 1964, the BBC had commissioned a series of interviews with theatre people the world over about their "take" on the Bard. Utpal (born in Barisal) had honed his skills as an actor with Geoffrey Kendall's Shakespeare Wallah troupe, an outfit of travelling players stepping straight out of Hamlet.

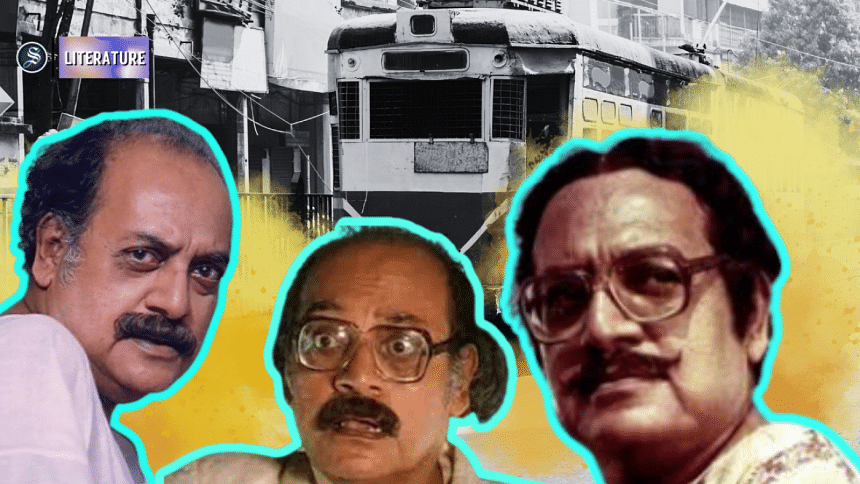

I cannot remember whether I got to Utpal's house by way of a battered tram slowly jangling its way past buildings waiting like film stars for Satyajit to audition them or, overcoming my dismay, gave way to the desperate entreaties of one of the–still then thirty-five thousand–rickshaw pullers to employ him, his legs grievously contorted by such work.

The dark little room where I talked with Utpal was bare but for the portraits on the wall of Lenin–Utpal himself sporting a beard like Lenin's, and, oh dear me, Stalin–here he would have parted company with Lenin's old protégé, M N Roy. Through the iron bars of the window came the twanging sound–like a sarangi–of what I took to be a street-seller carding wool. Perhaps it was.

What did Utpal say? I kick myself now that someone like myself with an interest in theatre, in dialogue, in utterance, failed to take more than a sketchy note or two of what theatre people in Kolkata were saying to me, the more so since "Auntie" has carelessly mislaid the 11-minute interview I taped with Utpal. Fortunately, Utpal gave another, very similar, interview shortly afterwards: "Taking Shakespeare to the Common Man".

I find it particularly intriguing now that the Shakespearean was every bit as committed as the Communist. Yes, Utpal, a fine and experienced anglophone actor, was concerned that Shakespeare would reach a far wider audience by being translated into Bangla. But he was also adamant the translations should remain as close as possible to the originals. He deplored adaptations, believing the Bard had no need of a helping hand.

Moreover, while an overtly political play such as Julius Caesar–whose Rome fostered the modern concept of Fascism–might go down well with a sophisticated city audience, for ordinary people in rural areas and small towns it was different: they preferred the raw emotion, the blood and guts of Macbeth, Hamlet, and Othello. These people deserved translations done by poets who felt and understood this essential emotion, as well as the high-flown language, of Shakespeare's originals.

Even more subtle in his approach, perhaps, was another theatre giant I met: Shambu Mitra. He too was a committed Communist but, as a guest of Moscow, was not impressed by the literalness of a socialist realism that would bring a real locomotive on stage. As it happened, the Biswaroop Theatre was even then running–forever it seemed–a play, "Setu", where the illusion of an oncoming train was created by a clever combination of sound and light on its revolving stage.

Shambu argued that the American academic Faubion Bowers was wrong to suggest the form of modern Indian theatre was "Western". While he was an admirer of several Western playwrights himself, Shambu thought the best Indian theatre drew its real strength from both classical and popular tradition, sentimental and melodramatic in the best sense of those words.

Shambu's journey towards a distinctly Bengali theatre had seen him adapt not only Ibsen's seminal play on the oppression of women, A Doll's House, but also O'Casey's Red Roses for Me, a stirring and inspiring account of armed Irish struggle across religious communities that could be seen, as in Bengal, as more of a class divide.

These two great theatre directors were still trying to find a way of taking theatre to the masses but had yet to take up the theatre of the people. Ironically it was Tarun Roy, a theatre director who was not committed ideologically–and perhaps on that account may have been overlooked–who actually took me to see the jatra.

What Tarun lacked in ideology, he more than made up for in enthusiasm, together with his wife, Dipti–out Nora-ing Nora, a dancer and musical composer as well as actor–Tarun ran an experimental Theatre Centre on the ground floor of their house down south in Chakraberia Road, at that time offering adaptations of Bankim and Sarat Chandra.

Running counter to the villagers streaming into the city for the Puja like one great river of flowers, we made our way upriver to Bandel, where the Roys had one of the few little brick bungalows that could safely be swathed and bathed in the light of diyas, before going on to Chinsurah, where the jatra was being performed.

The audience for the jatra was all any Marxist theatre director in Kolkata could have wished for. The masses stretched away in every direction–beyond sight and hearing–from the decorative pandal outside a shop, the door of which served as entry and exit for the actors. But, of course, they weren't masses: I described the scene to my mother in terms of the Kentish village where she lived and knew the particular people.

Once again I kick myself for failing to have recorded what was the subject of the play: I note only that it was historical and histrionic: evidently not about the mendacious Brits this time nor the mythological Ram. We sat there half the night, alternately attentive and gossiping, until a white mist rose up off the river, it grew surprisingly cool and we returned to the diya–lit bungalow in Bandel. Where the moon was–and it must have been there–I don't say. Perhaps I was just enjoying myself too much.

The next day, we returned to Kolkata to see the statues of the Goddess, divested of her fineries and returned to the mud of the river whence she had emerged–and so reminding us of our common fate. I took up again with the many students I had encountered during this everlasting week, all of them properly communist, though of bewilderingly diverse factions.

Some kindly fed this refugee from Morarjibhai's Gujarat parathas and kebabs–note, no hilsa–at Nizam's; others took me into their homes, more like monkish cells, and we drank beer, snacked on muri and argued about the ways forward for societies. The future then seemed to be socialist and Britain's welfare state and two-party system a fag-end of a capitalist past.

It would not be until I was at the other end of my life, at 80, that I stood on the crowd-filled campus of Dhaka University, again on the occasion of a Puja, this time Saraswati's. To the sound of bhajans and Rabindra sangeet, I joined the students in felicitating the Goddess of Learning in her manifold colourful images constructed by, wonderfully among others, those of the Department of Islamic History and Culture. What it is to be a 24-year-old student. Liberating.

John Drew is an occasional contributor to The Daily Star. A collection of his articles, Bangla File, was published this year by ULAB Press.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments