Takeaways from COP29

COP29 convened in Baku amidst worsening climate disasters and was touted as a turning point in global climate action. However, its outcomes highlight some very systemic shortcomings of the international climate regime. Though COP29 finally managed to agree upon a historic deal intended to accelerate climate finance and decarbonisation, the agreement falls frustratingly short of the urgency needed to combat the escalating climate crisis.

A deal too little, too late

On paper, the COP29 agreement promises more climate financing and ambitious decarbonisation goals for wealthier countries. However, the $300 billion in annual climate finance it pledges by 2035 has been criticised as a "paltry sum" because it falls short of what is needed to tackle the scale of the crisis. For a country like Bangladesh—struggling to keep its head above rising sea levels amidst wild weather—the deal offers little hope for respite. Poorer countries continue to bear disproportionate burdens of a climate crisis they did not cause, underscoring ongoing inequities in global climate action.

The agreement also contains no binding commitments and no real mechanisms for implementation. For this reason, it has been called "a band-aid on a gaping wound," as it treats symptoms rather than causes. Despite these commitments, record-high carbon emissions persist, and the agreement does little to alter this trend. Scientific consensus indicates that the world is teetering dangerously close to the 1.5 degrees Celsius warming threshold, beyond which lies a cascade of tipping points with devastating consequences. This requires urgent, immediate action—not in some undefined future. Yet, the results of COP29 fail to rise to this challenge when concrete measures are urgently needed. Time is running out, and every delay worsens the global predicament.

Once again, the voices of developing countries were drowned out by priorities set by richer nations. Issues like funding for loss and damage, support for adaptation to climate change, and technology transfer remain inadequately addressed.

The need for COP reform

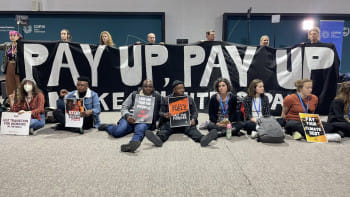

There certainly is a growing sense that COP climate talks are no longer "fit for purpose" and urgently need reform. The deep structural and functional flaws evident in COP29 highlight these shortcomings. These so-called inclusive summits frequently marginalise smaller countries, often at the behest of global powers and corporate interests. Procedural inefficiencies, a lack of enforceable commitments, and rampant lobbying by fossil fuel companies undermine the process's integrity.

To regain credibility, COP must transition from a platform of rhetorical commitments to one of binding agreements and fair representation. Crucially, such talks should not be hosted in countries that cannot—or will not—support the phase-out of fossil energy.

Who can lead the climate fight?

The spectre of Donald Trump's return to the White House in 2025 loomed over COP29, with concerns that his administration would torpedo the United States' commitment to global climate efforts. During his tenure, Trump pulled the US out of the Paris Agreement, and his remarks at COP29 indicated a desire to dismantle the current climate framework. A disrupted US role poses a very real risk of eroding fragile trust among countries and imperilling future climate talks.

This raises the question, with the US role in doubt, who will drive global climate action? The European Union has long taken the lead on climate change, but fragmentation in its politics significantly limits its capacity for transformative change. China, while a major emitter, has assumed leadership in renewable investment but faces credibility challenges. The most plausible leadership could emerge from coalitions of vulnerable nations and emerging economies, leveraging their collective voice to push for more ambitious commitments.

What should countries like Bangladesh do?

Bangladesh and other developing countries should seize this opportunity through COP29, charting their course while leading calls for global action. Resilience must be a priority through investment in strong adaptation measures like coastal defences, climate-resilient infrastructure, and sustainable agriculture. These countries should lead by forming alliances with other climate-vulnerable nations to demand just financing and technology transfer. They must also pursue greener growth on a low-carbon development trajectory to attract climate-friendly investment and gradually reduce dependence on fossil fuels.

Additionally, regional cooperation with neighbouring countries will help combat common challenges and build shared climate resilience for a more sustainable future. As the global climate regime faces existential challenges, the need for reform and equitable participation has never been greater. Bangladesh and other vulnerable countries must amplify their voices, hold powerful polluters accountable, and pursue self-reliant strategies to safeguard their futures.

The climate clock is ticking—and for countries like Bangladesh, it's ticking faster than ever.

Dr Selim Raihan is professor at the Department of Economics in the University of Dhaka and executive director of South Asian Network on Economic Modeling (SANEM). He can be reached at [email protected].

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments