The reform process and its discontents

Sheikh Hasina's despotic regime rigged three elections, destroyed every state institution, plundered the economy, committed grave human rights abuses, and ultimately fell after three blood-soaked weeks last monsoon. In his iconic speech at the Shaheed Minar on August 3, 2024, Nahid Islam demanded not only Hasina's resignation but also political reforms to ensure that such a regime never torments us again.

Without absolving the ousted despot of her many crimes, it has long been acknowledged that Bangladesh is in dire need of institutional and constitutional reform. Even during the 1991-2011 era of elected democracy, our highly centralised political system concentrated power in the person, and persona, of the prime minister. In such a system, losing an election could, and often did, endanger not only one's livelihood but also one's life.

This winner-takes-all, zero-sum politics did not necessitate Hasina's depravity, but it made Bangladesh particularly vulnerable to authoritarianism. That is why the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) had placed institutional and constitutional reforms at the heart of its future agenda.

The BNP's reform programme was founded on two core ideas following a free and fair election in the post-Hasina era: i) a set of independent commissions to examine the failures of our republic and offer recommendations; and ii) a government of national unity to implement those reforms.

In addition, the party proposed the establishment of an upper house, executive term limits, and checks on the power of the prime minister.

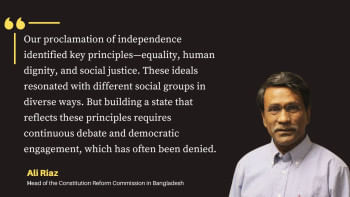

Hasina's flight from the country in the face of a popular uprising has, of course, altered the sequence of reform. Recognising the urgent public demand, the interim government formed several commissions in October. Headed by respected scholars and veteran activists such as Prof Ali Riaz, Dr Badiul Alam Majumdar, and others, these commissions worked tirelessly, producing volumes spanning several thousand pages in a matter of months.

A National Consensus Commission was formed in February to synthesise recommendations and solicit responses from political parties. Since then, we have seen their reactions. And unfortunately, it remains unclear how the process will move forward. The interim government has complicated matters by linking the reforms to an unnecessary dichotomy of a "minimum or larger package" and election timing between "December 2025 and June 2026." This framing has sown distrust and jeopardised the reform process itself.

Let's unpack this.

Reform proposals can be classified into two categories: those requiring constitutional amendment and those that do not. For the latter, where there is agreement among major parties, the interim government can begin implementation immediately. These include changes relating to the electoral process, the judiciary, and anti-corruption efforts. Fortunately, there is broad consensus on these matters.

Reforms to the election process should, of course, be prioritised. Yet none of these reforms require a longer timeline that would necessitate pushing the election to June. The claim that a "minimum package" enables a December election, while a "larger package" delays it until June, lacks credibility.

The constitutional reforms, however, are more complex. Here too, there is agreement between parties in principle: term limits for the prime minister, the creation of an upper house, enhanced female representation, and the independence of accountability institutions. But there are disagreements over specifics.

For instance, Prof Riaz's commission proposes a lifetime limit of two terms for the prime minister, while the BNP prefers a cap of two consecutive terms. The commission suggests electing upper house members based on the proportion of votes won in the lower house; the BNP prefers allocation based on seats won in the lower house. On female representation, the BNP proposes that 100 women MPs be selected proportionally by parties, whereas the commission recommends directly electing 100 women MPs.

To guarantee institutional independence, the commission proposes that appointments to key accountability bodies—such as the Election Commission, Anti-Corruption Commission, Public Service Commission, and Human Rights Commission—be made through a National Constitution Commission (NCC), which would include strong opposition representation. However, since the NCC would also have a say in key defence appointments, the BNP opposes it, even as it acknowledges the need to depoliticise these institutions.

Importantly, the BNP has not closed the door to further discussions on any of these issues. Yet the current reform process offers no viable pathway for progressing them.

If we take the chief adviser at his word, that no reform will be imposed on anyone, then, given the BNP's reservations, the logical next step is to hold an election. Parliament is the appropriate forum for debating and negotiating details of term limits, female representation, the upper house, and institutional independence.

If, on the other hand, there is a belief that an in-principle, pre-election consensus is essential—on matters like a proportionally represented upper house, directly elected female MPs, lifetime limits on the premiership, and opposition input in key appointments—then the current process is clearly inadequate.

Here, history may offer some guidance.

In the aftermath of the horrors of 1975—one-party rule, coups, and massacres—it fell upon Ziaur Rahman to rebuild the republic. He personally engaged a wide spectrum of political and civil society stakeholders to craft and enact a reform package. If Prof Yunus believes that the reform package proposed by Prof Riaz and his team are crucial, then he must lend his personal gravitas to secure a consensus among the parties.

Regrettably, the chief adviser appears more at ease mingling with global elites in Davos than engaging in the necessary give-and-take with local politicians.

There is another historical precedent. In 1991, the victorious BNP faced strong public demand to restore parliamentary democracy. At that time, civil society—comprising intellectuals, journalists, academics, development workers, and entrepreneurs—worked alongside politicians to forge consensus, resulting in the 11th and 12th constitutional amendments.

Today, we face another political impasse. The interim government seems either unwilling or unable to unite the parties around vital reforms. It is, therefore, time for civil society, non-partisan but politically conscious citizens, to step up. Instead of looking solely to the office of the chief adviser for salvation, we must directly engage political parties on key issues like a proportionally elected upper house.

The BNP has historically responded to reformist public pressure. It was born from the post-1975 reform movement. It restored the parliamentary system and codified the caretaker government. Civil society engagement with the BNP on reform, coupled with a demand for an election date, offers a far more effective path forward than the current charade of "minimum/larger package" and the December-to-June election timeline.

One final issue remains unresolved: even if there is agreement on the reforms, how do we ensure the parties actually implement them?

Jyoti Rahman is a writer and economist.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments