‘Human translation will continue, despite machines’: An interview with V. Ramaswamy

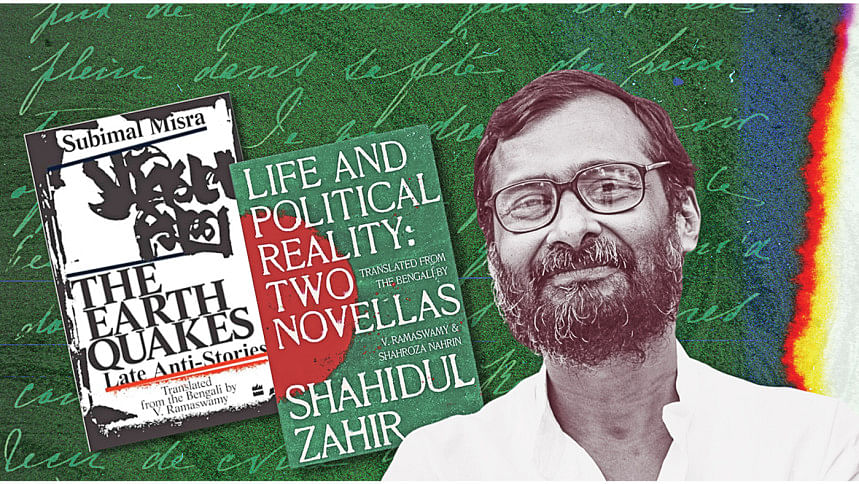

V. Ramaswamy is a translator and writer based in Kolkata, India. I had first heard of him in early 2022, when a new book of translations of Shahidul Zahir was being written about in newspapers here in Bangladesh and in India. Yet it would be his work on Shahaduz Zaman where I first experienced his craft. A translator of writers such as Subimal Misra, Manoranjan Byapari, and Adhir Biswas, I found his translations to be effortless forays into the bleak world of these writers.

Speaking with Ramaswamy on behalf of The Daily Star about his life as a translator, he also shared insights on his upcoming projects and, among other things, thoughts on whether AI could ever be a serious translator.

Tell us how your journey as a translator began.

My journey as a translator began almost by accident in 2005. During a casual encounter with my friend Dr Mrinal Bose, I asked him if there was one contemporary Bangla writer who he thought was worth reading; he thought for a moment, and said, "Yes. His name is Subimal Misra." And thus, with Dr Mrinal's prodding and pushing, I began translating Subimal Misra's short fiction. But after that initial start, I persisted with translating Misra because his writing resonated with my own background as a grassroots and community organiser and activist, working with the labouring poor of my city for two decades. I was selected for the Sangam House residency in 2011, and during the residency I was translating Misra all day, every day, one week after another. I would say that it was the Sangam House residency that made me a translator. After completing three volumes of Misra, I saw myself as a translator of voices from the margins. That was when I learnt about the autodidact writer Manoranjan Byapari, and received the novel Chandal Jibon from him. A three-month fellowship in Wales in 2016 enabled me to work on this. For me that was an apprenticeship in working on a long novel. So that's something about the journey to becoming a serious and critical translator.

I was born in a Tamil-speaking family in Kolkata, and my school, college and university education were in the English medium. I learnt Bangla for three years in elementary school, so I learnt to read the language. All my reading was in or via the English language. It was through my activist engagement that I really stepped into the world of Bangla, and then became proficient not only in the language, but also in my personal engagement with history, sociology, politics and culture of what I came to see as my land and my people. So I am an insider-outsider, or an outsider-insider, and that aspect is also ever-present in my translation endeavour.

You are currently translating Prodoshe Prakrito Jon, what drew you toward the works of Shawkat Ali?

It was my translation assistant, Srishti Dutta Chowdhury, who told me in 2020 about Shawkat Ali's novels, Prodoshe Prakrito Jon (The United Press Limited, 1984) and Narai (Bidyaprokash, 2012). She wanted to translate these, and asked me if I would join her. But it was the way she described these two novels that had a mantric effect on me. As it happened, Srishti was unable to devote time to this; also, following the experience of collaborative translation of Shahidul Zahir with Shahroza Nahrin, from Bangladesh, I thought I ought to induct a Bangladeshi co-translator for Shawkat Ali as well.

I had the consent from the late Shawkat Ali's family in a matter of hours. That was only because of my network and circle of friends in Bangladesh. Similarly, my eventual co-translator on the Shawkat Ali project, Mohiuddin Jahangir, was introduced to me by Asif Showkat, the author's son, now a good friend. Mohiuddin's PhD thesis was on Shawkat Ali. We completed the novel, Narai, titled as We Must Fight! in English. That will be out soon.

You have been part of multiple translation projects as a co-translator. How different is the process of translating in collaboration?

I had no plan as such to collaborate, it was just a sudden thought, and so I invited Shahroza to join me as a co-translator of the novella, "Life and Political Reality" (1988), by Shahidul Zahir. I had become acquainted with Shahroza Nahrin via Facebook. I arrived in Dhaka in early 2020 and sat with Shahroza for a few days; she read out, and I translated.

This first experience was a happy one, and it convinced me that when it comes to important texts, two is definitely better than one. Two people can share the ownership, responsibility and labour of translation.

I would like to think that this was also a good mentorship experience for my co-translator. Bangla needs a Mukti Bahini of translators, and so this collaboration-mentorship process can also be a means towards building more translators.

How do you go about choosing what to translate? Do you read the book as you go, or entirely beforehand?

With all the books I translated, the decision to take it up arose through specific circumstances, situations, and people. But I had my antennae and my informants, built up through embedded experience. I do not read the book first, I read it as I am translating. No reader reads a book as closely as a translator. One goes through the text multiple times, scrutinising every word, letter and 'matra'.

You once mentioned in an interview that your wife believed translating Subimal Misra made you more like Misra's writing, that is, dark. Is this something you consciously worry about? Being transformed through a work of literature?

Notwithstanding the barbs of my wife and friends, I never really thought about this! But I was definitely transformed by translating Subimal Misra, not in the limited sense of becoming "dark", but in terms of learning and growing. Translating Manoranjan Byapari was also transformative; I became the protagonist Jibon, as it were, a boy born into the hitherto untouchable Namasudra caste, and lived through the journey of his life. Likewise with Adhir Biswas, the son of an outcaste barber, who became a writer, editor and publisher. Translating him made me his soul kin. Finally, Shahidul Zahir. Translating him was like discovering a whole new world, at one's doorstep!

What do you think of machine translations in the sphere of literature? Should it ever be taken seriously?

I guess machines will gradually get better and better, but until then we humans will carry on translating. Like literature, translation is a human act, a human choice, and the translator brings his humanity to play in his or her work. And so what we get is a creative, human, artistic work. AI can write a short story or a novel. Will it ever be as good as anything humans have ever written? I don't know. But I don't think I would be interested in reading any literary work produced by AI. AI can generate images in a fraction of a second. But we will still look with awe at the work of the great masters. Will people stop expressing themselves in drawing and painting? Will people stop writing? So human translation will also continue, despite machines.

How do you deal with cultural nuances when translating from Bangla to English?

I guess one has to be embedded in the culture in order to perceive and sense the nuances. The translator must then bring this to the fore creatively. For instance, if someone addresses an older person as "tui" rather than "apni", that conveys something about sociology. About classism being ingrained in the culture. A particular word or term may be very significant, from the perspective of history, or politics, like Ponchasher Manantor, or Mir Jafar, or Dandakaranya. The translator has to be ever alert. Readers of a translated work thus also learn about the history, politics, culture etc of a people.

There is something else I'd like to share in this context. When one translates, say, proverbs, there would be equivalent expressions in English. Like, "as you sow, so you reap". But there is an expression in Bangla, "katth khele angra hagbe" (if you eat wood, you'll excrete charcoal). Rather than translate that into a tame expression like "as you sow, so you reap", I would like to give the reader a peep into the psyche of the speakers of Bangla, the pungency of their speech etc. So I would translate the original expression itself.

Shahriar Shaams is a journalist at The Daily Star. Find him on Instagram: @shahriar.shaams.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments