Ensure safety compliance from high-rise owners

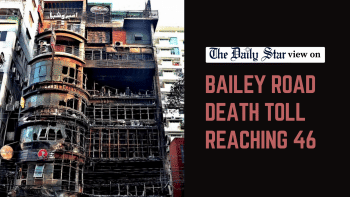

As more information surfaces about the building code and fire safety violations in the Bailey Road mall where a fire claimed at least 46 lives on February 29, the government cannot remain in denial that the burden of recurring fire tragedies in our cities rests mostly on its agencies tasked with monitoring and enforcing compliance. While Rajuk, fire service, and city corporations are once again attempting to shift responsibility onto each other, a familiar pattern emerges—systematic negligence and lack of coordination among these vital departments.

A major issue, as per a report by this daily, seems to be the lack of a unified legal definition of "high-rise" buildings. Currently, the Fire Prevention and Extinguishing Act defines any structure with over six storeys as high-rise, requiring an NOC from the fire service. However, the Building Construction Rules 2008 and Bangladesh National Building Code, which Rajuk follows, define high-rise buildings as those with over 10 stories or exceeding 33 meters in height. This inconsistency further intensifies as the fire prevention act, which empowers the fire service to file cases against non-compliant buildings, is currently halted due to a High Court stay order. This means that even after identifying 2,118 risky structures in 2023, the fire service can now issue warning letters only.

Consequently, a seven-storey building like the one on Bailey Road did not obtain an NOC from the fire service during construction, nor was it forced to implement fire safety measures despite being identified as a fire hazard. Similarly, every major fire incident in Dhaka over the past few years—Siddique Bazar, New Market, Bangabazar, Krishi Market—had a common theme of well-marked risky buildings meeting their inevitable doom. The fire service claims it sends copies of fire safety violation letters to the city corporations and Rajuk. However, no action follows. Fire officials say buildings like the Bailey Road's shouldn't house restaurants without safety measures, yet they get licenses. City corporations claim they cannot demolish high-risk structures due to court orders in favour of owners, while Rajuk faces allegations of ignoring widespread violations and enabling illegal operations.

Clearly, we need a comprehensive action plan to address these underlying issues so that the relevant agencies can ensure compliance from all building owners. But first, the government must acknowledge that the repeated fire incidents in our cities are a direct result of systemic issues, and it must hold relevant agencies accountable for their failure and negligence.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments