My heart doesn’t desire to speak about Sultan

I had once written extensively about S.M. Sultan. Why? Because it felt essential to make our 'art authorities' aware that he was a rare talent, although many were unwilling to accept it. Thus, the pen became my last resort.

The reason for writing was not just to assert that Sultan was a highly acclaimed artist and more. Concerning Sultan, my efforts had three objectives. Firstly, to establish him as an artist among his people. Secondly, to gain international recognition for him. And thirdly, Sultan was very fond of children and always had a longing to do something for them. So, I thought of assisting him in this regard.

1.

My first write-up on Sultan had attracted a significant number of art and literary enthusiasts to the artist. Many readers of that piece even contacted me personally. Notable figures among them included Professor Abdur Razzaq, Poet Abu Zafar Obaidullah, Poet Sayeed Atikullah, and banker-cum-businessman Lutfar Rahman Sarkar. It wouldn't be incorrect to imply that this first piece had introduced the artist to a number of prominent individuals. Sultan and his art were rediscovered by many, and there was a sudden wave of enthusiasm about the painter among the youth. During that time, the government came to his aid, honoring him by designating him as a resident artist and arranging a regular stipend.

However, it was the young Tareque Masud who initiated a grand plan: he created a documentary film based on Sultan. The only source of inspiration for his work was my first write-up. His film titled 'Adam Surat' brought the painter into the limelight. Hasnat Abdul Hye went on to write a book about him, in which he also acknowledged my piece.

In independent Bangladesh, only two art exhibitions were held featuring Sultan's works. The first was held at the Shilpakola Academy in 1976, and the second took place at the Goethe Institute (the German Cultural Centre) in 1987. I made contributions to the second exhibition.

As mentioned before, Sultan had a strong fondness for children. During his attempt to inaugurate the 'Bhrammoman Shishu Shorgo' (a boat designed to carry children and help them experience natural scenery), I served as the General Secretary of a foundation known as 'Bangla-German Shompriti'. To help him realize his dream, I managed to gather around 9-10 lakh Taka from my trip to Germany. The boat was successfully constructed. I had additional plans with Sultan in his hometown of Narail, but due to a shortage of funds and other reasons, they couldn't be implemented.

There are two more reasons behind these endeavors.

I believed that Sultan's identity as the son of a farmer was a major factor that had hindered him from being recognized as an 'artist'. If he hadn't been the son of a farmer, our art establishment might not have hesitated to give him the recognition he deserved. I am convinced that our art establishment deliberately deprived Sultan of the acclaim he was owed. Many within the establishment were aware that Sultan was a painter of international stature, a national treasure who should have been celebrated. Therefore, the effort to overlook him was intentional. I decided to put an end to this negligence.

Secondly, I too am the son of a farmer. I saw how another farmer's son was struggling to thrive on his inherent talent, to rise despite the snub of the art establishment. It was then that I realized my purpose was the same as Sultan's. From the bottom of my heart, I still believe, like the famous painter Vincent Van Gogh – our Sultan too is a painter of world eminence. Within our subcontinent, there's none to match Sultan's caliber. My belief has been further strengthened after my trip to America.

I had heard a number of museum officials discussing Sultan. They seemed very keen about acquiring his works. Unfortunately, I had none of his works. If I had any works, they could have fetched a fortune.

However, I am pleased that Sultan finally earned himself the title of an Artist in our country. Our younger generation has become aware of his great talent and magnitude. It's a pity that the painter's generous dream concerning children has not come true till today. The future also can't be predicted. But inspired by him, I started a school. The painter was alive then. He had spent some time in the school with the children. Regrettably, I couldn't run it for more than a year. The Ershad regime of that time forced me to close it. I was able to reopen it in 1995. I had to appeal for funds to a number of sources and organizations and still continue to do so. I am not sure how long I will be able to continue it.

2.

Sultan was a revelation to me, a revelation that has not yet ended. He was a sublime source of inspiration, capable of inspiring even the most ordinary person to be creative. In Bangladesh, no other artist is comparable to him. Let's talk about a boat mechanic named Prafulla. Whenever Sultan was in Sonargaon, he used to stay with Prafulla. At that time, Prafulla was forty years old and worked as both a boat mechanic and a farmer. Sultan aimed to unleash the artist within him.

In response to Sultan's insistence, Prafulla hesitated, saying, 'Master, how can I become an artist?'

Sultan motivated him, saying, 'You can. I know you can.'

Later, whenever Prafulla could find time, he used to draw with colored pencils on large sheets of paper. Today, if you observe his drawings from a distance, they appear reminiscent of Sultan's style. Only Sultan could have set the course of action in motion for such a dream to come true.

In my opinion, Sultan's paintings possess an eternity and brilliance rarely found in other artists. Jainul Abedin was also a renowned artist, but it is Sultan's universality that sets him apart from all others. This particular characteristic is absent in most artists within our country.

We witness consciousness about environmental issues today, but he had markedly emphasized the issue way back in 1986. I once undertook some initiatives to obtain UN recognition and brand him as an environmental artist. Had he lived a little longer, surely I would have reached my goal.

The reason our governments are compelled to recognize Sultan is because his position is fortified by a tremendous amount of public support. He has many admirers. However, I feel that the governments are not thoroughly and consistently sincere in their efforts regarding Sultan. During the BNP regime, the government had allocated funds for him, but it was stopped by the succeeding government.

At a seminar arranged by Bengalis in Atlanta, I met the Deputy Minister for Culture, who informed me that his government had initiated a grander plan for preserving Sultan's heritage. A committee was formed to monitor a substantial fund, and acres of occupied land were reclaimed despite legal obstacles. Later, I discovered that nothing was actually done.

The boat was anchored in Chitra and had a hole at the bottom. It wasn't even taken out of the water. The artist's half-finished drawings, along with his personal items, were damaged by rats. About eight Ansars sat idly around his residence. This is how we treat a great painter and honor the heritage he left behind. It's a crime that infuriates me.

There are plenty who shower Sultan with accolades. Seminars and symposiums are held on his birth and death anniversaries. Among the aficionados are those who didn't initially want to recognise him. Sad to see that people's genuine love for the arts isn't there any longer.

Sultan was a man who stood out from the crowd. A few days ago, after his death, a news report was published. It said that a snake was seen resting on top of his grave and that it attacked whoever tried to approach the grave. A photo of the snake was published too. This proves that the passion Sultan cherished for nature was reciprocated by nature in return.

3.

Sultan bhai's awe-inspiring creation was his own life story. He was brought up in a Hindu family, all-inclusive in his ideology. I believe the neglect shown to him stems from prejudice because he came from such a humble background. Despite being a senior craftsman, his talent was undermined due to his origins. It's a shame that none of his paintings are seen hanging at the national museum, and those who run it appear unapologetic. We should be ashamed as a nation.

Interestingly, a prominent art critic wrote a book on Sultan, although he is the same one who once didn't recognize him as an artist. What's new about that? Such is the norm of our critics. It is only once you become famous that the greatness within you gets revealed. Until you reach that level of fame, no one cares. Nowadays, everyone seems to write a book on him. That's good, but what's the value of it if it cannot properly explain the benchmarks for evaluating an artist, analyze, and prove why he should be treasured? These books have little value.

In 1976, General Zia-ur-Rahman was at the helm of power. I was under police observation due to my political affiliation with JSD. One day, while coming out of the International Hostel, I felt like someone was following me.

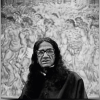

I proceeded to Kamalapur. It was evening, probably the month of August. The circular gallery of the Shilpakala Academy was being built at that time. I spotted a tall man in a cloak. He had long hair and was smoking joints intensely. Suddenly, he stopped smoking, tucked his hand inside a pocket, and took out a live cat from it. He then kissed it and handed it over to a short man standing behind him. Until that point in time, I neither knew nor had even heard of Sultan. However, later I came to know about the short man. He was called Batu and was an ardent follower of Sultan.

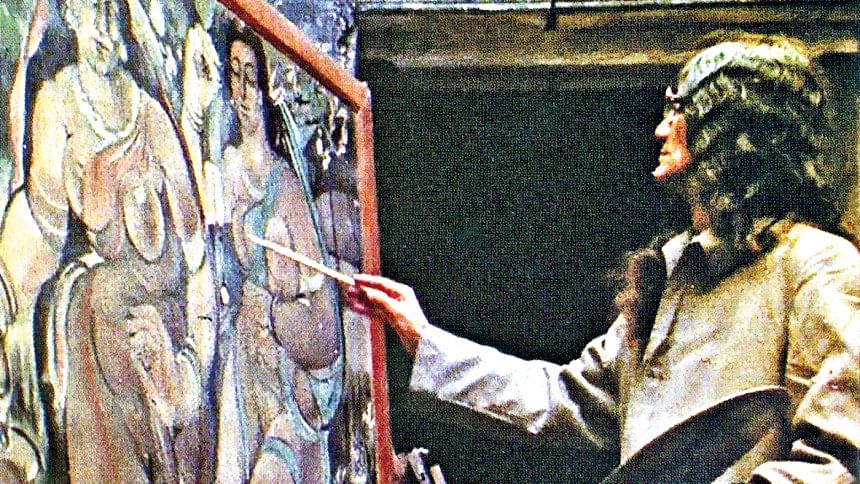

Batu's mother was also Sultan's follower. Batu was a barber by profession. He would stand still when Sultan used to draw, with the cat in one hand and joints in the other. Sultan used to generate tremendous speed while drawing, as if he were visualizing the farmer, river, banana tree, and thus a whole locality would be sketched. I have never seen anyone draw like that, but I heard that Michelangelo used to paint in the same manner. I was glued to him when he worked and visited him many nights just to watch him at work.

Then came the day of Sultan's painting exhibition. Abul Fazal, the then-adviser to President Zia, was selected to inaugurate the show. He came from the same locality as I did, so I went to him and said that I wanted to accompany him on the exhibition day. He asked why, and I said that I wanted to witness the reactions to his paintings and see how they were received.

The crowd on that day was massive. Attired in a long cloak, Sultan bhai delivered an idiosyncratic speech, mixing English and Bengali. The media extensively covered the exhibition. However, I was amazed to see that none of the news reports focused on the aspects of his paintings. Instead, the reports covered his personal life, particularly his eccentricities. They reported, for instance, on how he never stayed anywhere permanently, how he was fond of pets like snakes, cats, lizards, etc.

Being curious, I personally approached a number of people, and no one could provide a convincing analytical judgment about his paintings displayed in the exhibition. Even Jainul Abedin merely said, "Sultan paints well indeed…" but that was all. I then went to several art critics, and all of them could come up with only dull replies.

Another aged prominent critic of today, whose name I don't want to mention, insultingly stated that Sultan hasn't yet learned to hold the brush. The same opinion was shared by another renowned poet. This infuriated me. While I held Sultan in high regard as a painter of global repute, they said that he couldn't hold the brush. But who would listen to me?

I suspected it might be class discrimination again. If they were forced to recognize a farmer's son like Sultan as an esteemed painter, they might face a serious identity crisis. I took this to be an organized conspiracy. To think in this manner seemed like a divine responsibility to me. In order to gain deeper knowledge, I took up painting. I learned to draw and paint. It was very challenging indeed. Concurrently, I wrote a booklet of around 50 pages. Syed Atikullah funded the publication of 5000 copies on an urgent basis and began dispatching them to people of significance.

4.

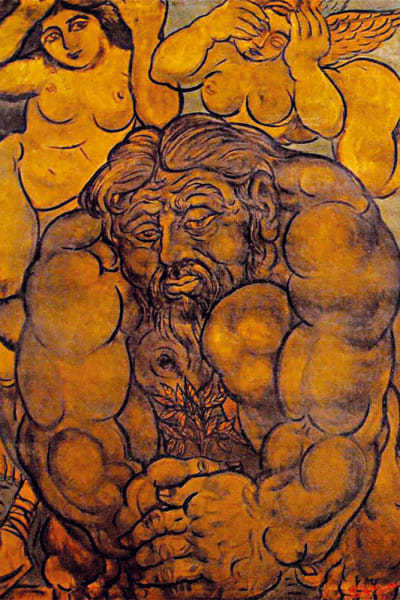

I am not afraid to admit that my personal choice of paintings differs from those created by Sultan. I am an admirer of abstract work, whereas Sultan bhai's subjects are specific communities. Looking at his paintings is akin to looking at Bangladesh. His works portray both contemporary and traditional farmers, the very foundation of civilization. Much has already been discussed about his style, so I don't want to dwell too long on this.

But I want to mention that before the Renaissance period, European artists focused on portraying Jesus and Mary as superhumans. During the Renaissance, these biblical figures started to appear more human - Mary was depicted as a farmer's daughter, and Jesus as a tortured being. Similarly, Sultan's chosen topic revolves around the humiliated and deprived farmers of this country. He aims to show how farmers create their own form of art from the soil.

Aside from the instances mentioned above, I had another memorable opportunity to witness Sultan's technique while I was residing at Dhaka University's International Hostel – where he had drawn bare female bosoms on a wall. It was beyond my imagination how beautiful they could be. Such eroticism can only be visualized through fantasy. In later stages, these topics were depicted differently, more as food and consumables. However, initially, they represented an erotic yet latent sexual appeal. The difference in portrayal also reflects Sultan's transformation as an artist.

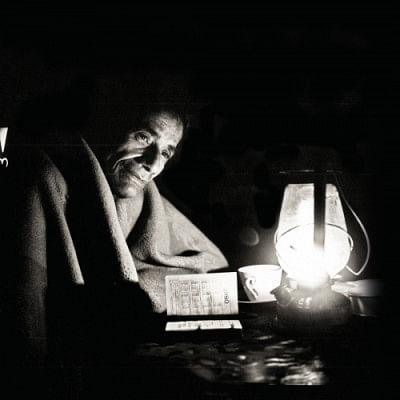

Dear readers, you might have noticed the disorganization in my writing, which is why my heart does not yearn to write another piece on Sultan. Perhaps someday, I will write a novel about him. I want to conclude by saying that my Sultan bhai was an exceptional being, his paintings are incomparable, and his life is inspiring. Indeed, his life itself was a remarkable work of art.

Ahmed Sofa (1943-2001) was an eminent litterateur and activist.

Translated by Shahriar Feroze. He is a journalist.

The original article was published in The Daily Jugantor on August 17, 2000.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments