Learning the ropes

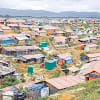

The Bangladesh government has been globally lauded—and rightfully so—for welcoming with open arms, once again, the persecuted Rohingya people with whom the country has a checkered history. The Rohingyas came to Bangladesh in droves in 1978, 1992, and the 2010s. But at this juncture, many are wondering just how the latest influx of Rohingyas—the highest yet, numbering over 600,000—is going to pan out in the longer term. With Bangladesh—as overpopulated and resource-strained as it is—now hosting almost a million Rohingya refugees, the absence of a coherent plan in dealing with a crisis not of its own doing is turning out to be detrimental. Conditions at the camps are deteriorating and the dangers of child and sex trafficking are becoming more and more real as we speak.

The dilemma we are facing perhaps is a result of any government having to tow the difficult line between humanitarianism and realpolitik: At what point does ceaselessly taking on the burden of more and more refugees turn into an opportunistic tool for the sending country (in this case Myanmar) to achieve its internal objectives? Is Myanmar not taking advantage of Bangladesh's compassion to rid the Rakhine State entirely of the Rohingya?

With a cloud of uncertainty hanging over the repatriation talks, it looks like the Rohingya crisis at our doorstep is only going to balloon with time. It also makes one wonder why Bangladesh—which is no stranger to hosting refugees—has not been able to do a better job of refugee management, particularly with regard to the Rohingya. If criticising the handling of the latest influx of Rohingyas seems unfair or premature, then what of the thousands who have come here previously and continue to live in squalid camps, with their movement restricted and with little to no chance of ever getting a proper education?

A major reason behind Bangladesh's inability to better manage the crisis is the utter failure of the international community—the usual suspect—to pressurise the Myanmar government into bringing an end to the repression of the minority in the first place, so that Rohingya refugees stranded in Bangladesh would feel confident enough to go back. I say the international community because refugee management isn't a one-man show. However, that does not completely absolve the host country of its responsibilities to do its best to protect the rights of these people who have left behind everything they have ever known in fear of persecution. Sadly though, that's not how it always works out.

Refugee crises are ridden with dilemmas. A dilemma for the oppressed to leave or stay. A dilemma for governments to condemn or remain silent. A dilemma for countries to refuse or let refugees in. And once they've done their part to take in a certain "quota", there's yet again a dilemma about doing "too much" for fear that this would act as a pull factor. This has been the case with the Rohingya refugees who have come to Bangladesh in previous exoduses and have had to face restrictions such as limited access to education and no permission to work despite being here for decades.

"Refugee crises are ridden with dilemmas. A dilemma for the oppressed to leave or stay. A dilemma for governments to condemn or remain silent. A dilemma for countries to refuse or let refugees in. And once they've done their part to take in a certain "quota", there's yet again a dilemma about doing "too much" for fear that this would act as a pull factor.

Bangladesh isn't alone when it comes to being precautious about becoming a haven for refugees. A similar line of reasoning seems to have also been taken by developed countries like Australia which are far better equipped to handle refugee crises of the scale that we are facing. Australia's controversial offshore processing centres—long regarded as its Achilles' heel in its history of immigration policy—were established in order to "stop boat arrivals" of asylum seekers to prevent deaths at sea and "break the people smugglers' business model" (as per the official narrative).

But there lies an underlying objective of minimising the "pull factor"—much like the rationale behind imposing restrictions upon Rohingyas who have been living in camps in Bangladesh for years. In fact, multiple Australian immigration ministers have put forward the not-so-subtle argument that taking in refugees from offshore detention facilities is akin to "putting sugar on the table". The issue of asylum seekers and refugees has a long, ugly history of politicisation in the country and has become an intense area of criticism globally.

In humanitarian crises, governments inevitably find themselves between a rock and a hard place: Striking a balance between the moral responsibility of granting refuge to the persecuted and treading with enough caution so as to avoid negative consequences. In light of the critical situation at the Manus Island immigration detention centre—where refugees and asylum seekers have been defying the closure bids by Australia and Papua New Guinea and, as of writing this article, had until Sunday to stay in the camp—it is clear that the Australian government isn't ready to soften its stance on asylum seekers arriving by boat. That is extremely unfortunate because there is yet no sign of an end to the inhumane treatment of refugees and asylum seekers holed up in the offshore detention facilities.

Despite commonalities of ethical dilemmas, no two countries have the same experience in dealing with a refugee crisis—and there's a lot that one can learn from another. For instance, the symbolic significance of the Bangladesh government's opening the borders to hundreds of thousands of Rohingyas is immense: It should be a lesson in compassion for developed countries like the US and Australia that can do much more than they are doing to resettle the most vulnerable refugees. Differences in context aside, the number of refugees being resettled by both Australia and the US pales in comparison to the number of Rohingya refugees we have sheltered in the past few months alone. That being said, there is also a lot to be learnt for Bangladesh from countries like Australia and Canada when it comes to emulating key features of settlement service programmes.

In Australia, for example, where the resettlement intake for 2017–18 has been increased to 16,250 spots (not nearly enough), an extremely well-structured, comprehensive refugee resettlement programme has been put into place for humanitarian entrants. From ensuring that its governance involves all tiers of the government (federal, state, local) to the provision of medical benefits, interpretation and translation services, and skills and education programmes, Australia's refugee resettlement programme can serve as a model/blueprint for countries like Bangladesh where a strong mechanism of refugee management is lacking. This does not mean Bangladesh should also come up with a "resettlement programme" for the Rohingyas; rather what it can do is take inspiration from existing models of refugee programmes, such as the one in Australia, to come up with its own mechanism to better handle the crisis. Because right now, Bangladesh seems to have nothing close to a plan of action to deal with the massive numbers of Rohingya refugees.

Managing such humanitarian crises comes with extreme complexities to which there are no one-size-fits-all solutions. It requires the Herculean task of skillfully balancing the art of diplomacy, assuaging public opinion, and re-allocating limited resources. But if there's one overarching lesson to be learnt, it is to ensure that the traumatising state of in-between, that is often a result of governments wanting a quick fix, does not prolong the cycle of suffering and exploitation of hapless victims of persecution—whether it be asylum seekers and refugees stranded in Nauru or PNG or undocumented Rohingyas in Bangladesh stuck in limbo.

Nahela Nowshin is a member of the editorial team at The Daily Star.

Comments