How the youth's perception of Bangabandhu soured under Awami League

August 15 this year was unrecognisable compared to how the day had been observed over the 15 years of Awami League rule.

The day this year came just 10 days after former prime minister Sheikh Hasina, in the face of a student-led mass uprising, was forced to resign and flee the country. Her government was subsequently dismantled.

Her government had declared August 15 a National Mourning Day and a holiday to solemnly remember the assassination of Father of the Nation Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and the murder of most of his family members in 1975.

Yet, on the day of Hasina's fall, statues of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman were torn down in various places, and Bangabandhu's historic residence at Dhanmondi-32, which had been turned into a museum, was set on fire.

The interim government subsequently cancelled the public holiday, and many individuals were stopped and harassed at Dhanmondi-32 on August 15, apparently for trying to pay respects at the residence of the country's first president.

But what does this mean? Does the new generation really think so little of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman? How did it get to this stage?

We spoke to some youngsters and asked them about their perception of who Sheikh Mujibur Rahman is, and how that perception changed over time.

Rubama Amreen, 15, says she can't recall when she first learned about Bangabandhu, but admits that she has been hearing the name for as long as she can remember.

"It was more like knowledge instilled within us from birth," she said. The one thing that stood out to her when she learned about the Liberation War in school was the "incessant glorification of Bangabandhu, which was strange, especially compared to how we were taught about other world leaders".

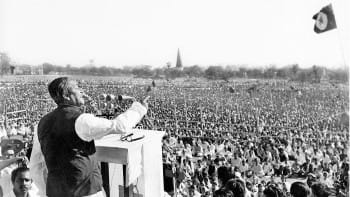

Sakib Rahman (not his real name), 24, points out what was missing in history lessons about Bangabandhu, "In our social science textbook, the history mostly revolved around the Liberation War and a big section about his March 7 speech. Nothing was mentioned about the Awami League rule between 1972-75. Back then, I thought of him as a national hero who was a saint."

However, the post-war period in Bangladeshi history was recent enough that many youngsters had the chance to learn about Sheikh Mujibur Rahman's time in power from family members who saw it first-hand. The advent of the internet, on the other hand, has made it doubly difficult to limit anyone's knowledge of history simply to textbooks or other government approved media.

Sakib's interest in that period of history was recent. "I got interested in the history of post-war politics during the recent protests. Books like Bangladesh: A Legacy of Blood, Jasod er Uthan Poton, and 3 Ti Shena Obbhutthan o Kichu Na Bola Kotha, etc. painted the real picture about Sheikh Mujib for me. I knew his rule wasn't that great, but after knowing the details, it completely changed how I viewed him."

Anindya Alam, 24, shared how his perception was shaped by his family's honesty about the history of that period, "My family background is diverse. My father's side has been very pro-Awami League and has political history while my mother's side, post-liberation, has been very critical of the Awami League. As I grew up and my family began to have more honest conversations about history with me, I had access to two different narratives."

For Anindya, while one side reaffirmed the narratives taught by his textbook, the other side told him about the loot, the nepotism, the extrajudicial killings, and the terror of the Rakkhi Bahini.

Even if an honest reading of history is not consistent with what the younger generation has been taught, it doesn't explain the disdain with which many in this generation have treated the memory of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, especially since the fall of the Hasina government.

Some think the previous Awami League government is to blame for that.

Wasima Aziz, 19, said, "The previous government shoved the idea of Bangabandhu being an unquestionable figure down everyone's throats, to the point of mockery. I think the previous government tainted the image of Bangabandhu themselves, by overdoing it to the point of no return."

Anindya Alam added, "Bangabandhu had a fairly positive perception among Bangladeshis and the Hasina regime took advantage of that. The previous government, in Bangabandhu's name, tried to rewrite history. By attributing every little success to him, the previous government tried to justify their authoritarian regime. All good things happened because of Bangabandhu. But people aren't stupid. We recognised our oppression, and we attributed that to Bangabandhu, because all oppression was justified in his name."

Mesbah Kamal, professor of history at Dhaka University, echoed some of the same sentiments as the students, and pointed out exactly where Awami League got it wrong.

"History is non-linear in nature, every action has a reaction. The post-1975 attempts to erase Bangabandhu from our history brought about a serious reaction in 2009 when Sheikh Hasina came to power. She tried to establish Bangabandhu as the Father of the Nation and the commander-in-chief of the Liberation War. However, in the process of doing this, Sheikh Hasina often presented her father in a way as if Mujib was their family property and her family has a special authority over the country. No one, especially the young generation, was on board with it."

Pointing out the Awami League's mishandling of the history of Bangabandhu, he said, "Another dimension is the overprojection of Bangabandhu, the tendency to force him onto the nation. Bangabandhu should have been portrayed as the champion of nationalist and humanitarian spirit, but that was not done.

"Chhatra League and the Jubo League could have done that among the students and the youth, they could have engaged in research and creative pursuits around Bangabandhu. Instead, they resorted to slogan-heavy speeches and a policy of subjugating the youth through force. This approach took them miles away from the young generation and also helped promote a negative attitude towards Bangabandhu."

So, what comes next? How do the young generation want to approach the figure of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman now, out of the yoke of the Awami League?

"Frankly, the history of Bangabandhu should be regarded in the same way as that of any other historical leader. There's no need to glorify him or put his name in the mud. Acknowledging both sides not only provides a better chance to understand the heritage of our country, but also to understand what it means to rise up to a position of that much power and act as a representative of a huge population," said Rubama Amreen.

Anindya Alam suggested, "People must be given an authentic historical account of Bangabandhu and his regime. Whether people decide to view him as the Father of the Nation or not should be left to the people. The people of this nation have never been given a choice. I hope the future is different. I hope the younger generation of Bangladeshi students are encouraged to form their own opinions."

Historian Mesbah Kamal extends hope for the future too, "Bangabandhu was a politician, he may have made mistakes alongside making many correct decisions. The young generation could have been told what the Awami League learned from his successes and mistakes, what other parties should learn from that period.

"The contribution of Bangabandhu in the period between 1947-1970, in 1971, and in rebuilding the war-ravaged country is undeniable. But these histories don't just belong to the Awami League or Bangabandhu. The history that has been told until now has not done justice to people like Sher-e-Bangla A K Fazlul Huq, Maulana Abdul Hamid Khan Bhashani, Comrade Moni Singh, Muzaffar Ahmed, Syed Nazrul Islam, Tajuddin Ahmad, and Colonel Abu Taher. Students understand this.

"I feel that whatever distance may have been created among the youth in understanding the contribution of Bangabandhu will change over time in the synthesisation process, and Bangabandhu will eventually be recognised and respected in general."

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments