A Tale of Newspaper Reading

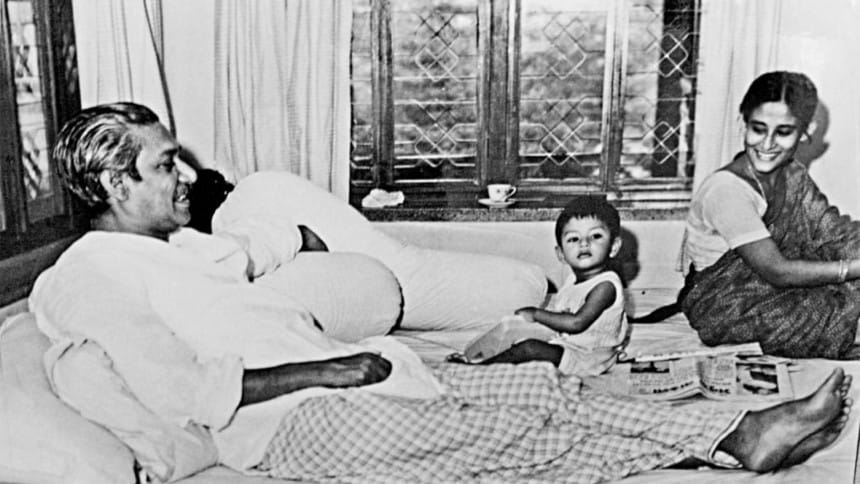

After waking up in the morning, we all used to gather, one by one, at my mother's bedroom. With a cup of tea in everyone's hand and newspapers scattered on the bed… everyone would read a news item one after another, while others would listen to it and give their opinion. Sometimes, there would be debates on what was written in the newspapers or what messages the papers wanted to give. All would give their opinion as per their thoughts. This way, both the morning tea party and our newspaper reading gained momentum.

Our days would start in this way, and it would continue for at least three hours. My father got ready to go out. We also got ready to go to school. My father was very punctual in going to his office. We learned the lesson of punctuality from him.

Noticing our newspaper reading and the different opinions we gave, one day my father asked: "Tell me, who read which news items more attentively?"

We were surprised. No one could utter a single word. Kamal, Jamal, Rehana, Khoka uncle, Jeny and I—we all were there. Even little Russel was also among us. He did not read, but was busy snatching away the newspapers.

When he saw we could not say anything, my father disclosed what would be of interest to each of us. We were surprised. How attentive he was! My mother mostly read small news items on the inside pages, particularly those on social issues. She also kept track of what happened where. Kamal read sports news mostly. As did Jamal. I was more interested in the literature pages and cinema news. So, everyone had their favourite topic.

From her early age, Rehana paid special attention to newspapers. Sitting in the veranda and putting her on his lap, my father would drink tea and read the papers. When Rehana saw a newspaper, she would try to grab it, as if she could read it. And then, when we came to our Dhanmondi residence, she started reading newspapers with the rest of us. When she grew up, she developed the habit of reading newspapers quite diligently. She would read every news item whether it was related to cinema or other issues. There were many stories, poems and quizzes on the page for young readers, which never failed to catch her attention.

Rehana now lives in London but she reads the newspapers of the country regularly through internet. Not only does she read the papers, she also sends me messages whenever she reads something about people's suffering, asking me to help someone or the other, questioning why an incident took place there, etc. For example, there was a news story during the coronavirus pandemic. A beggar had saved money to build a house but then donated it for the treatment of Covid-19 patients. The news of his generosity deeply moved her. She informed me of the matter immediately. So we built a house for him. This is how we have been able to stand by people—because of Rehana's compassionate heart and her habit of regularly reading newspapers. Staying abroad, she always thinks about the welfare of the people. Being constantly informed about what is happening in her country through the pages of the newspapers, she serves the people.

Kamal and I passed our childhood days in our village home of Tungipara. At that time, it took two nights and a day to go to Tungipara from Dhaka. That meant, if we boarded a steamer in the evening of a day, we had to pass the next day on the steamer and then it reached the Patgati station late at night. And from there, it took around two hours to reach Tungipara by boat.

Newspapers did not reach that area regularly. At that time, we had yet to learn the value of newspaper reading. But one newspaper would reach our house and we observed how the grownups took a huge interest in reading it.

We came to Dhaka in 1954, during a tumultuous period in politics. We did not have the company of my father. He was elected as a member of the provincial assembly. He became a minister too. He was naturally very busy and would return home at the dead of night, when we were already asleep. In the morning, Kamal and I went to school. Sometimes when my father returned home to have lunch, we met him. This brief interlude was very precious. No matter how brief, those moments when we got our father's affection and love became the most cherished gift for us.

He sacrificed his life for the people of Bengal. He dedicated his whole life for the welfare of the deprived people of Bengal.

Then he was detained in jail. When our father was free (out of jail), we hardly got his company due to the crowds waiting to see him. And when he was detained in jail, we could meet him for only one hour in every 15 days. That was our life!

My mother used to lessen our sorrow with her affection and love. And my grandparents and uncle Sheikh Abu Naser used to meet all our demands. He brought us everything we needed. And my father's cousin, Khoka Uncle, used to stay with us always. Khoka Uncle was always willing to extend his help—from taking us to school to going to lawyers' residences regarding the cases filed by the Pakistani government against my father.

My mother liked to read. My grandfather used to keep various types of newspapers in the house. In his "The Unfinished Memoirs", my father wrote about how my grandfather would buy and read newspapers. That's how my father acquired the habit of reading newspapers. And from him we learned to become avid newspaper readers too.

My father had an intense connection with newspapers. When he was studying in Kolkata, he was involved with the publication of a newspaper. Mr. Hashem supervised the newspaper and Tofazzal Hossain Manik Miah served as its editor. My father was involved with the publicity of the newspaper.

At that time, two other newspapers, "Millat" and "Ittehad", were also published. My father was involved with those newspapers too. In 1957, my father got involved with another newspaper named "Natun Din". Poet Lutfar Rahman Zulfiqar was its editor.

After the creation of Pakistan, the "Ittefaq" newspaper was published with the financial assistance of Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy. Tofazzal Hossain Manik Miah was the editor of the newspaper. My father was also involved with the newspaper and worked for it.

In 1957, after getting the charge of Awami League general secretary, my father resigned from the cabinet. He stepped down from the post of the minister to concentrate on organisational activities to strengthen the foundation of Awami League. In 1958, Ayub Khan imposed martial law. My father was arrested. On December 17, 1960, he was released.

After his release, he started a job at Alfa Insurance Company, as he was banned from politics at that time. He even had to inform the police station and intelligence agency if there was a need for him to go out of Dhaka.

But this period brought for us a great chance to spend more time with our father. Waking up at dawn, we used to go for morning walks with him. At that time, we lived at a residence at Segunbagicha. Ramna Park was under construction then. We used to walk to the park from No 76—our house in Segunbagicha. There was a small zoo which had several deer, peacocks, birds and other animals.

After returning home, my father used to sit with the newspapers and have a cup of tea. My mother and father used to read the newspapers together. They used to discuss different issues.

A children's page named Kochikachar Ashar was published in the Ittefaq every week. I remember one Jalal Ahmed who used to write articles under the title "Japaner Chithi" (Letter from Japan). There was a section for puzzles too. Sometimes I would try to solve the puzzles. Sometimes I was successful in solving them!

At that time, newspapers had specific pages for literature. It was our regular task to read the newspaper sitting in the veranda and having a cup of tea. My mother used to read newspapers very meticulously. After lunch, my mother used to sit with newspapers and letters from the post box.

The "Begum" newspaper would be delivered at our residence regularly. There were also Reapers, National Geography, Life and Reader's Digest—some were weekly, some monthly and quarterly publications. The literary newspaper "Samakal" was also kept at the residence. My mother liked it very much. Write-ups in the "Begum" and "Samakal" were favourites of my mother.

At that time, my father started publishing a weekly named "Banglar Bani". A machine was set up after taking a place in Segunbagicha. Banglar Bani was published from there. My brother Moni was studying at Dhaka University. He was given the charge of the newspaper.

My father was arrested again in 1962. At that time, we shifted to the Dhanmondi residence. When my father was captive in jail, newspapers were the only way to get information from outside. But those newspapers were censored before delivery.

If you read "Prison Diaries" written by my father, you will realise his interest in reading newspapers during his captivity. It revealed how important newspapers were in a prisoner's life, particularly if one is a political prisoner. However, my father did not face any hassle in getting information from outside, because my father easily got information from those who worked inside the jail or fellow prisoners.

When my mother went to meet him, she apprised him of the country's political situation. And she conveyed my father's directives to the party leaders and workers. Particularly, all the credits of the movement, which was built up following the announcement of the Six-Point demand, were of my mother. She had a sharp memory.

I too know the companionship of newspapers during imprisonment. I used to buy four newspapers with my own money when I was in jail during the 2007-08 period. But it was not possible to take newspapers of my own choice. The then government gave names of four newspapers and I took those. But at least, I could get some news.

My father, Bangladesh's president and Father of the Nation Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, was killed brutally by assailants on August 15, 1975. At the same time, 18 of my family members, including my mother and three brothers, were also killed.

My younger sister Sheikh Rehana and I were abroad at that time. Though we were spending our life as refugees after losing all our near and dear ones, we used to collect newspapers and went through those regularly.

In 1980, I went to London from New Delhi and stayed with Rehana for a few days. We used to take children to school and back home—for that, we got one pound for each child. Usually, the first thing I did with the money would be to buy a newspaper. On my way home from school, I would buy a newspaper, bread and other essential items. If I couldn't have at least one paper in my hand, my whole day would seem dull and dreary.

I always thought of my father and mother. They had taught me to think about the well-being of the country's people and thus created in me dutifulness towards the people. They also taught us the principle of simple living and high thinking and created awareness amongst us about humanity and dutifulness. Since I was groomed with that ideology, I have been able to accomplish the important task of serving the nation. I have been able to undertake plans and thus implement those in running the country through giving priority to human welfare. And the people of Bangladesh are getting its benefits.

Criticisms and discussions will remain in political life, but if one works with honesty and integrity and can take decisions with self-confidence, then its good results will surely reach the people.

The mass media could create awareness in society, and after forming the government, I gave all the government newspapers to the private sector.

But those who were previously against nationalisation or were very critical of it made accusations when I went for privatisation; they even waged a movement and staged hunger strikes too.

I often wonder why they had started making criticisms against my father after enjoying all the facilities as the jobs of journalists, representing the newspapers that could exist in the war-ravaged country, were nationalised, and they started getting their salaries from the government.

On the other hand, when I left all of those media with the private sector, again they resorted to all means—waged a movement, made criticisms, staged hunger strikes—as I privatised the government newspapers. Why? I know no one will be able to answer this.

When Awami League formed the government in 1996, there were only a small number of newspapers in Bangladesh, and those were also controlled from a special place. There were the state-run radio and television. But there was no radio or television in the private sector.

Acting on my own initiative, I opened up the private sector. In this regard, I had two targets—one was to create employment and the other was to let our culture flourish—incorporating modern, technology-based culture and art with the current era so that modernism could be brought forth and the people at the grassroots level could enjoy its benefits.

In our election manifesto of 2008, we had pledged to build a Digital Bangladesh, and digital devices are now making a special contribution to our daily life, especially as it helps us tackle the challenges we face because of the coronavirus pandemic. For this, we could maintain our economic activities by taking timely steps. We opened up the mobile phone industry in the private sector in 1996, and for this, mobile phones are now in everyone's hands.

Bangladesh's film industry started at the hands of my father, and there is a huge scope for entertaining the mass people by making this industry modern and technology-based. Besides, this industry could play a role in the overall development and also in poverty alleviation.

We are now going through an abnormal situation due to the worldwide coronavirus pandemic. I am hopeful that this black cloud will go away soon and a new, bright sun will rise. I wish that the lives of all become successful and beautiful. May everyone stay healthy and safe—that is my desire.

The article was previously published by Bangladesh Sangbad Sangstha (BSS).

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments