A fragile institution with a strong legal framework

The elections, the Election Commission (EC), the government and political parties are parts of an interwoven web of a complex relationship. In 1972, Justice M Idris was the first chief election commissioner of Bangladesh. In those times, the EC's role was not very challenging; political situations were in favour of competitive elections, and the government machinery was more professional than political. Although the opposition was insignificant in terms of parliamentary seats, ground-level politics was quite vibrant. Various political parties like the Jatiya Samajtantrik Dal (JSD) and National Awami Party (NAP-Muzaffar and NAP Bhashani) and many other small and large parties were active. After that, political parties were banned under the Fourth Amendment of the constitution, and Bangladesh became a one-party state.

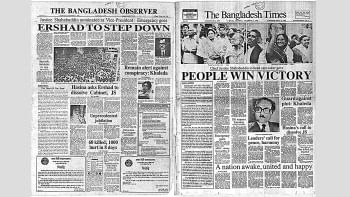

The single-party system changed its course after 1975. Post-1975, military or military-backed governments took over and continued to be in power till 1990. Elections in those days were arranged just to provide a mantle of legitimacy to the regimes. The post-1991 situation brought some qualitative changes in electoral politics. Under the interim government of Justice Shahabuddin Ahmed and three subsequent caretaker governments, four largely credible and acceptable elections were held. However, crises cropped up after each election, too. It was fierce in 1996 when the BNP was in power, and the Awami League was in the opposition; the then BNP government solved the crisis by amending the constitution, and they were unseated and sat in the opposition. The next crisis resurfaced again during the BNP rule while the AL led a movement in 2006. Again, the BNP was unseated, and the impasse came to an end when an army-backed caretaker government took over power for two years.

Now, given the ongoing stalemate over the issue of a caretaker government system, is there any hope that the AL government will bring another constitutional amendment and relinquish power? As commoners, we have no idea. The EC is a constitutional body that can function if all other institutions of the state function properly. The EC cannot be effective in isolation – it is virtually a helpless institution in this case. They can hold up the constitution as a piece of paper, but they cannot enforce it. You can have a gun licence, but if you have no gun and are required to fire, you are susceptible and vulnerable. So is our EC. Now and then, they are firing loose guns and echoing the ruling party's rhetoric, which is more damaging. They should be the conscience keepers of the nation.

Under the current AL government, three ECs have been appointed. Until 2013, the municipal and city council elections were more or less competitive, with good participation. However, the subsequent elections since 2014 were marred with irregularities of various types. The process and outcome of all elections were challenged. Brig Gen (retd) Dr M Sakhawat Hussain published a very important book titled Electoral Governance: The Role of the Bangladesh Election Commission, which was based on his PhD research. In the book, he presented a comparative analysis of the ECs from other countries in South Asia. We can see that our current legal framework of the EC is one of the best and most powerful in South Asia. But if you look at its performance, we are, ironically, the worst in the region. Although the Indian EC law is more lacking than ours, the institution itself is the best performing in South Asia. Journalist and economist Prannoy Roy and psephologist Dorab R Sopariwala, in their book The Verdict (2019, Penguin India), crowned the Indian EC as the country's best constitutional institution.

The Indian EC works smoothly and independently, retaining high levels of public confidence. Such big-scale elections do not take place in any other countries, but the Indian EC has maintained its towering respectful image for a long time, largely due to said "confidence" of the people. The second factor is bureaucracy. The civil service of India abides by the EC's instructions to the dot, which is why the country can hold staggered elections and reveal results after a month.

Such confidence in the bureaucracy and EC are vital, which is unfortunately absent in our country. One of the many reasons behind low voter turnout on election days is the lack of people's confidence in the political parties' honesty, credibility and ability to fulfil their promises. On top of it all, the general distrust towards the electoral and civil bureaucracy as well as the EC is paramount in Bangladesh.

In the 70s, violence mainly revolved around polling centres and campaigns. But now, it has taken various forms. Before elections, people are arrested and kept captive under threats and police harassment. All this discourages the public from going to the polls.

Our government, political parties, bureaucracy and electoral machinery are not people-centric. Despite the many movements for democracy and human rights, people are scared to get involved in such activities. It has reached such a level of alienation that citizens keep suffering in silence, with little to no scope for asking for redressal. Over the past 15 years, people have been made to believe that their votes are no longer required.

Our new, young voters did not have the chance to see the liberation struggle. They are less passionate about our history, but more concerned about their life and living in the future. To them, their future in this country is bleak and uncertain. Therefore, many of them do not have much enthusiasm for political activities and elections. The older-generation voters still feel passionate about politics and voting as they have participated, seen, heard and read about the politics of liberation and its aftermath. Of the new generation, who are between 18 and 35 years of age, many of them are clueless in this regard. They do not have a clear picture of why they should vote for any particular party.

The national election is the climax of politics. The country is engulfed in a very different and difficult political dynamics. Those who are not in power are made to believe that participating in any election under the ruling regime is equal to committing suicide. The last two subsequent parliamentary elections (2014 and 2018) and all local elections and by-elections confirmed this notion. How the impasse can be broken, nobody knows. One dominant opinion is that the prime minister of Bangladesh is the only person who can save the nation from a deadly crisis, and who alone is holding the key to the deadlock. If she unilaterally attempts to hold an election, that may bring a political and governance disaster which the nation may not be able to endure. We cannot afford – nor do we deserve – this failure.

Prof Tofail Ahmed, PhD is a local governance expert and political commentator. He can be reached at [email protected].

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments