What should an election-time government look like?

An election-time government performs the special task of holding or supervising a national election to ensure smooth transition of state power. Noting its importance as early as 1972, Surangit Sengupta, an opposition member in the Constituent Assembly of Bangladesh, proposed the formation of a special type of government during the 1973 general election. He spoke of dissolving the ruling Awami League government of that time and forming a "caretaker cabinet" comprising representatives nominated by the president from parties that participated in the country's liberation movement.

In reply, Dr Kamal Hossain, who headed the process of drafting Bangladesh's constitution, argued that this proposal went against the fundamentals of parliamentary democracy and therefore could not be accepted. He, however, assured that during the election period, the incumbent will act as a "caretaker government." Explaining the body's nature, he said the election-time government could not make any policy decision 90 days prior to the polls. Being educated in the United Kingdom, among other places, on constitutional law and practice, Dr Kamal correctly represented the essence of the Westminster system.

However, the above debate has persisted, although in different shapes, throughout the political life of independent Bangladesh, mostly due to successive governments' failure to maintain fairness in the election process.

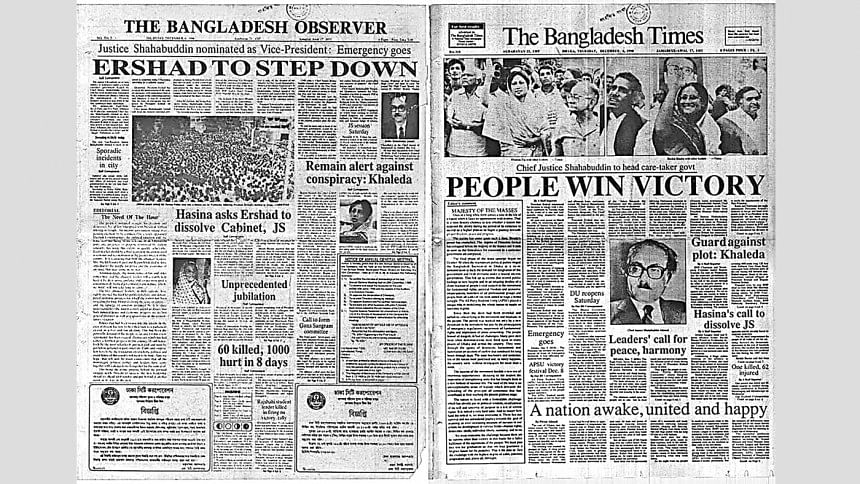

The controversy over the role of General Ershad's ruling party, or to say it more correctly, its inability and unwillingness to hold a free and fair polls gave rise to the formation of a consensual non-party election-time government in 1991, and later to a constitutional arrangement for establishing election-time governments in 1996.

Unlike the political caretaker cabinet Dr Kamal argued for, and much like the spirit of Sengupta's proposal, the constitutional design of 1996 stipulated dissolving the political government and forming a "non-political" caretaker one during the polls. Such bodies successfully oversaw three (four if we count 1991) general elections until 2009. Based on a controversial Supreme Court judgment, the arrangement was annulled by the 15th amendment of the constitution in 2011.

Following this amendment, the bitter division among political parties has reignited. The beneficiary of this amendment, that is the incumbent Awami League and its allies, insisted on holding polls under the party, and others rallied in favour of reviving the system. In between these two, a compromise for forming an all-party election-time government was sometimes offered but had never been discussed seriously by the confronting groups.

Bangladesh is about to witness another general election in 2024. The future of its democracy yet again hinges on the nature of the overseeing government.

Theoretically, an election-time government may take various forms in democratic culture. In the Westminster system, the incumbent generally continues as a caretaker government (for example, the UK government in 2019) to hold polls in the interim period between the parliament's dissolution and formation of a new government. Its activities are limited by customs and conventions of introducing new legislation and taking major policy decisions or initiatives.

In such democracies, the caretaker government may also be put in place in cases of resignation of the head of state (Belgium in 2020) or getting a vote of no confidence. In other cases, it may be formed as a result of a political settlement or peace agreement with members different from the immediate past regime (Tunisia in 2011 and Nepal in 2012). In countries where coalition governments are frequent, it may turn into a caretaker government with or without new members until negotiations to form a new coalition succeed (coalition governments in the 1990s in Japan).

Irrespective of the formation, two features are more or less common in the above governments. First, they are defined or understood as bodies operating between the election schedule's announcement and formation of a new government. Second, they carry out only day-to-day functions and abstain from making any new law, policy or administrative measure that may affect the election's outcome.

Unlike the above examples, Bangladesh's caretaker government was a unique institution. It was established by the constitution as a permanent foundation, and the members were essentially non-partisan, having no stake in the election's outcome. It was evaluated as a positive innovation both domestically and internationally.

Pakistan later followed Bangladesh's example. The former's 18th and 20th constitutional amendment allows for non-party election-time caretaker governments. The only major difference is that the body is formed primarily through consultation with both the ruling and opposition parties.

The election-time governments in Bangladesh largely succeeded in holding free and fair polls and regaining public confidence in the election process. One major testament to the success is the unanimity of all the major parties, including Awami League and BNP, for the retention of this system, which was expressed during consultation with the constitutional reform committee formed in 2011 by the AL government. This consensus, however, was not honoured when AL annulled the system unilaterally by capitalising on its absolute majority in the parliament.

The next two elections in 2014 and 2018 were widely criticised. Civil societies and the opposition have thus raised serious questions about the capability of the present system to ensure fairness in the next general election.

Our constitution says little about the "caretaking nature" of the election-time government. It declares independence of the Election Commission (EC) in exercising its functions. This independence, however, is subject to this constitution and any other law which may be promulgated by the parliament (Article 118).

The constitution obliges all executive authorities to assist the EC to discharge its functions (126) and guarantees that the president shall, when so requested by the EC, make available to it such staff as may be necessary (128). It also forbids the court to pass any order in relation to an election for which a schedule has been announced, unless the commission has been given reasonable notice and an opportunity to be heard (125).

These provisions may be interpreted as conducive to holding a free and fair election. But we have never seen the EC taking any proactive role to prevent or punish serious and obvious irregularities during elections held under a political government. Unlike commissions of caretaker governments, it never took measures like reorganising public and police administrations during polls, ensuring independence of the state-run media, creating a level playing field for the opposition, or enforcing the code of conduct and election rules. The EC members have been mostly drawn from public officers known for their loyalty to the ruling government and are found to be unwilling to exert their independence during the election process.

Under the prevailing circumstances, it becomes imperative to initiate a political dialogue for exploring all options to establish an election-time government, under which the EC, public and police administrations, and the judiciary may act independently. These options include reinstituting the caretaker government by constitutional amendment or invoking the process under Article 106, forming an all-party government with a different head, and reconstituting the EC with members nominated equally by political parties that ruled post 1990.

We must keep in mind that there really is no alternative to restoring faith in the election-time government. If mistrust and frustration over polls continue to prevail, national unity, solidarity, and strength will crumble further; the government will face the crisis of legitimacy deepening; and institutions will keep failing to deliver, leading to the economy suffering even more. We cannot afford to accept these.

Dr Asif Nazrul is a professor of law and researcher on constitutional and environmental laws.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments