For successful polls, administrative overhaul is a must

The Election Commission (EC), a constitutional body established during the country's inception, plays a pivotal role in overseeing elections in Bangladesh. Drawing from my personal experience as a returning officer in 1996, I can attest to the significant authority vested in the commission by the constitution, enabling it to ensure free and fair national polls.

Bangladesh has approximately 40,000 voting centres, each featuring five to six booths, totaling two lakh booths. Each centre is led by a presiding officer, with an assistant presiding officer and two polling officers assigned to each booth. Additionally, law enforcement agencies, including the police, Ansar, Rab and BGB, serve as patrolling forces, with the army deployed as a rapid response unit during national elections.

During the Gaibandha-5 by-polls, the EC monitored individual centres centrally via CCTV and detected irregularities that jeopardised the integrity of the polls. Subsequently, it made the decision to cancel voting, a move widely applauded. Following this decision, a comprehensive inquiry was conducted to assign responsibility.

Enforcing the law necessitates strict penalties for violations, and the commission establishes a code of conduct that all political parties and candidates must adhere to before the polls. With returning officers under the authority of the EC, collaboration with other agencies is essential for enforcing the code. In addition to law enforcers, judicial magistrates are an integral part of the election process. They can issue immediate orders in cases of breaching the code. However, the success of these efforts depends on the overall election environment.

In instances where polls are held under the governance of a particular party, local administrative bodies responsible for enforcing the code of conduct often struggle to impartially apply the rules. This creates a disparity between government party candidates and those from the opposition, as the former frequently flout regulations to their advantage. Opposition candidates often face restrictions on their campaign activities and may even experience arrests prior to the polls, rendering them unable to remain in their constituencies.

The 2018 election highlighted such challenges when the main opposition party participated despite the widespread arrest of its supporters and activists. This forced many to go into hiding and hindered their ability to secure polling agents for every booth, crucial for verifying voters' identities. If the ruling party exerts control over the administration and law enforcement agencies, they can significantly influence the election outcome through ballot rigging.

A looming question remains over the EC's effectiveness in conducting the forthcoming election. The constitution has bestowed upon it the necessary authority for ensuring an equitable and just electoral process. All officials involved in this process are, from their appointment starting on polls day till 15 days after the polls, considered representatives of the EC and require protection. However, the commission alone cannot guarantee this safeguarding; government support is imperative since all entities operate under governmental directives. If the government does not genuinely desire an impartial election, the EC's commitment alone will not suffice in delivering a truly free and fair election.

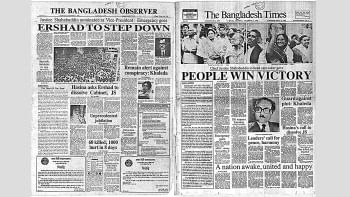

Crucial for such an election is the creation of a level playing field. If all political parties do not receive equal opportunities, the electoral process will not be universally accepted. Regrettably, tangible efforts toward establishing such parity are currently absent. The initial national polls in 1996 were marred by controversy and lack of participation. However, the government, pressured by the Awami League, implemented the caretaker government system, leading to grassroots administrative reconfiguration.

This reconfiguration serves as an effective measure by disrupting the partisan nexus. It need not involve a large-scale overhaul; I recall that during Justice Habibur Rahman's caretaker government, only 15 deputy commissioners were transferred. In 1996, the same individual served as the returning officer for two elections, with the first being controversial and the other hailed as free and fair.

Given the current government's uninterrupted 15-year tenure, pervasive partisanship has infiltrated every sector, resulting in numerous biassed appointments to critical positions. So, a substantial administrative reshuffle has become imperative. If the government genuinely supports the EC in fostering a conducive election environment, as they presently claim, government officials at the grassroots will work diligently, even without transfers.

In essence, should the government remain dedicated to impartiality in the electoral process, it would empower the EC, enabling it to exert influence on returning officers to ensure fair conduct.

Ali Imam Majumder is a former cabinet secretary.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments