Why BRAC should transform its experience into knowledge

I first met Sir Fazle Hasan Abed in 2012 at an invitation-only meeting in Washington, DC. He presented BRAC's development philosophy to a group of US policymakers, scholars, academics, and think-tankers at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, located in Washington's political heartland. Based on my brief interaction with him at that meeting, I wrote an opinion piece which was critical of what I thought was BRAC's lack of adequate attention to environmental stewardship in its development strategy ("Environment and Fatalism," The Daily Star).

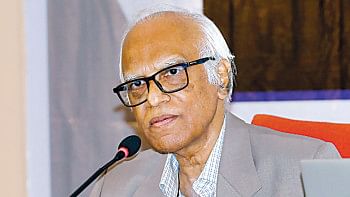

I was pleasantly surprised to see the TDS piece reposted on the BRAC website a few days later. I didn't understand the significance of this until I met Sir Abed again in 2017, when I joined BRAC University's Department of Architecture as its Chair and got to know him well. This was a person with an extraordinary ability and humility to allow constructive criticism to be a part of his development vision, humanised by a genuine empathy for the downtrodden. Most heroes talk and their followers listen. Sir Abed was an unusual hero who listened. He spoke from within or simply sat on the other side of the table, and spoke and listened in equal measure. This is why we often saw him among the people, poor women and children, listening to their stories with genuine interest. This image of a listener, of course, didn't mean that he wouldn't take the toughest decisions when needed.

Sometime in 2017, I approached Sir Abed with a proposal. The context of the proposal was this: Bangladesh has become a quasi-pilgrimage site for development workers around the world, who want to understand this South Asian country's remarkable feat in development from below or grassroots development. Media statements like Bangladesh's "development surprise" and "by many metrics, Bangladesh's development trajectory is a unique success story" are increasingly becoming common. Global pundits like Amartya Sen paid glowing tributes to Bangladesh's social advancements, particularly women's empowerment.

I told Sir Abed that this development story, despite its many flaws and frailties, and the one in which BRAC played a pivotal role, needed to be transformed into knowledge for ordinary people to understand and internalise it as a fundamental condition for realising their full potential. I was, of course, not referring to the ivory-tower, academic knowledge cloistered within a vast range of disciplinary jargon and peer-to-peer loop, inaccessible to most people, but to the kind of easy-to-understand knowledge that could catalyse broad behavioural transformation as a foundation for the next generation of development. I argued that time had come to transform Bangladesh's development story into an instructive narrative that can empower people to believe in themselves. I told Sir Abed that BRAC is great, but very few people outside it knew how this organisation flourished as a non-governmental organisation, how it survived many challenges, and how it sought to achieve its goals despite many roadblocks.

BRAC's work at the field level, since its founding in the early 1970s, has produced a vast body of data that could now be mainstreamed as knowledge of the past, present, and future of Bangladesh's development. I reasoned with Sir Abed that this knowledge production would be possible, even if partially, by creating a people-oriented "museum of development," a contentious but worthy site for transforming experience into operative knowledge.

This museum would display the history, in all its complexities and contradictions, of Bangladesh's development from the lens of BRAC's field experience and global exchanges. This is where school children would come as part of their curriculum to understand what development meant for Bangladesh in the wake of the country's independence. This is where college students would learn from the infographics and related exhibits showcasing Bangladesh's social and economic growth. This is where tourists, both local and international, would find another Bangladesh—resilient, progressive, and challenged—beyond the frivolities of the "basket case." I argued that not converting BRAC's 50-year experience into knowledge would be a lost opportunity, since that very knowledge could be the vehicle for people to graduate to the next generation of entrepreneurship.

Sir Abed was not convinced. I was perplexed as to why a visionary like him would not see the potential of knowledge as the propeller of Bangladesh's development in the 21st century. He was reluctant to entertain the idea. I slowly understood why. First, he thought that this "museum" would become a Sir Abed shrine, a hagiographic memorial of a larger-than-life saint. Given the empathetic human dimension of his personality, such "idolatry" would be antithetical to his worldview. Second, he may have thought that development in Bangladesh was still a work in progress, as millions still face economic hardship, and by no means were we at a stage in which we could feel complacent about successfully achieving economic and social freedom. And, third, a museum might be viewed as an arrogant memorialisation of perceived success.

Despite Sir Abed's lack of interest, I went ahead to introduce the idea of a museum of development as a class project to third-year architecture students at BRAC University. To my utter surprise, Sir Abed facilitated our visit to two potential BRAC-owned sites, one at Purbachal, on the eastern side of Dhaka, and the other near Gulshan-1, on the northern edge of Hatir Jheel. When we finally completed the project after about three months, he came to see the final outcome and asked the students about their philosophy of development and the challenges of displaying its past and future in a museum setting. I knew deep down that he would have appreciated the idea of "exhibiting development" as a form of operative knowledge for people to visualise self-improvement as an achievable goal.

The BRAC leadership should consider such a museum as a tangible tribute to the legacy of Sir Abed. This 21st-century museum, along with its research wing, will not mummify and glorify Bangladesh's development history, nor would it be a shrine for him. Instead, it will be a knowledge centre, mainstreaming holistic development as a state of mind.

Adnan Zillur Morshed is a professor, architect, architectural historian, and urbanist. He teaches in Washington, DC, and serves as Executive Director of the Centre for Inclusive Architecture and Urbanism at BRAC University.

Email: amorshed@bracu.ac.bd

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments