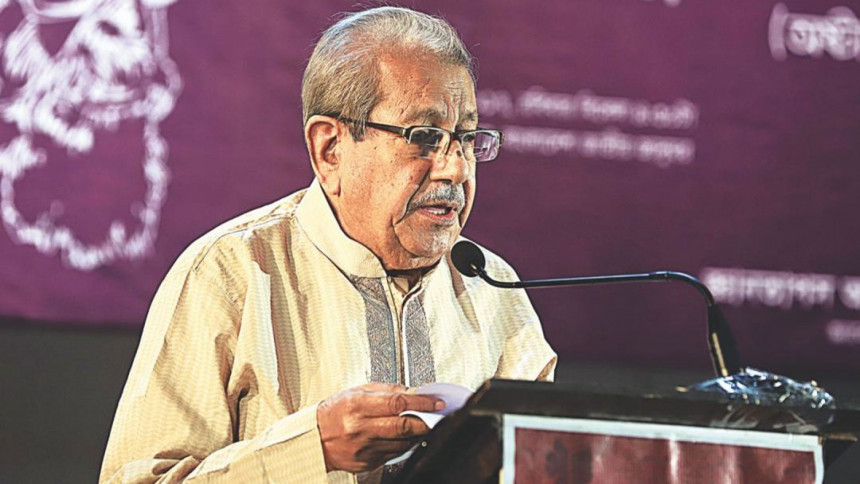

In memory of Prof Anisuzzaman, a scholar of Bengals past and present

I arrived in Dhaka, some years ago, as an outsider twice removed. First, I had grown up in Kolkata; second, I was a graduate student in Chicago. My knowledge of Bangladesh was from books, the fine print of which chafed against my eyes in the sparse light of American winters. When I first read Anisuzzaman's magnum opus, Muslim Manas O Bangla Sahitya, the past came alive with startling clarity, not just as something to be described, but as a set of questions to be confronted. These questions were fundamental: who are we, and how has the Bengali language made us who we are today? How can literature—this activity of utter futility and beauty—shape human beings as they evolve through time and through politics?

I still remember my first meeting with Professor Anisuzzaman. I had taken to Dhaka as if it were my own city, feeling at home in the endless traffic jams and periodic azaans. A friend had passed on Anis sir's number to me, and I had asked him how I could possibly introduce myself to this impossibly famous and elderly scholar. You need not worry, he assured me, Anis sir is kind to everyone, and he loves young people. He was right, and I had an appointment.

I arrived to see him in his apartment, simple but warm and beautiful. He had round-the-clock security. By this time, I had reread many of his crucial books, works that are integral to Bengali literary and political history. I was carrying a fountain pen as a mark of tribute and gratitude. He smiled when I thrust it awkwardly in his hands and I stuttered some more. In person, he seemed both towering and yet curiously fragile. He asked me why I wanted to study what I did. I told him that I had a peculiar relationship with the Bengali language. I loved it deeply as the medium of my self-expression, as the language in which my favourite writers wrote. But until graduate school, growing up in Kolkata meant that I was not entirely cognizant of Bengali Muslim history. I wanted to rectify that. I also told him that, when I wanted to understand how Hindus and Muslims felt towards each other, historically as well as in our own politically turbulent modernity, I had turned to his writing in desperation. One of the first people in Bengal to write a book on manas (mind? heart? sensibility? consciousness? mentality?), Anis sir's contribution to our divided inheritance of the Bengali language was exceptional in every sense. His scholarship on Bengals past and present connected past identity with present reality like nothing else did, and made a Bengali from the other side of the border understand the lived experience of the Bangladeshi subjectivity.

In the many tributes to this exceptional man that have appeared since his passing, we understand that Professor Anisuzzaman, "national professor" who single-handedly oversaw the cultural life of a nation, was himself an embodied history. Kolkata's beloved Anis da, known as Anis chacha to the cultural intelligentsia of Dhaka, and Anis sir to students, readers and followers, famously came to political consciousness at Dhaka University in the aftermath of the 1952 Language Movement. Intimately engaged as one of the key intellectuals and freedom fighters in the 1971 Liberation War, he was instrumental in both conceptualising and implementing the linguistic nationalism on which Bangladesh has been premised for nearly half a century. In our conversations, I tried—again, as an outsider—to make sense of the fundamental question animating my own generation ("millennials" in American parlance): what kind of national identity emerges out of a deep, intimate connection to language and literature?

For the generation prior to his—made up of the intellectuals who conceptualised a Bengali Pakistani identity—the very idea of East Pakistan was a renaissance of sorts. While historical records demonstrate that Partition was an electoral process ultimately engineered by the Hindu bhadralok, a majority of Bengali Muslims welcomed separatism because of Hindu cultural hegemony. In 1943, for example, the octogenarian poet Kaikobad bitterly remembered the way in which Hindu writers had once expressed amazement that a Muslim poet could write Bengali, even if they praised him. Trailblazing Nazrul was perhaps the only exception who gained absolute acceptance from the Hindu literary cosmos. After 1947, Pakistan brought its own set of problems, language policy being foremost among them. Abul Mansur Ahmad's dream of cultural autonomy gradually became impossible to implement. And, at the moment when language became the site of resistance, reclamation, and innovation—a radical reimagining of what politics could accomplish in the 1950s and 1960s—Anisuzzaman, studying with greats such as Muhammad Shahidullah, Munier Chowdhury, and Muhammad Abdul Hye, came into being as a unique political phenomenon. He was a political humanist and, in independent Bangladesh, he persisted in this work of interrogation, reconstruction, and radical reimagination of the politics of language.

When we think of earlier humanist scholars in Bangla on both sides of the border—Haraprasad Shastri, Abdul Karim Sahityabisharad, Dinesh Chandra Sen, Jasimuddin, Suniti Chatterji, Muhammad Shahidullah, and others—we realise that they dug into the past in order to make sense of the present. Literature represented the search for personal and collective identity. That enterprise became a more critical activity in the East Pakistan years and, arguably, an even greater challenge in Bangladesh. After 1971—after the mass killings of intellectuals and the destruction of documents—new edifices had to be built, and whatever remained had to be preserved. It was in this context that Anisuzzaman emerged as foremost among a generation of scholars including Ahmed Sharif, Ahmed Sofa, and Serajul Islam Choudhury, figures who saw literature as a constant dialogue between past and present, between Hindus and Muslims, even between Muslim and Muslim. He struck a balance between his own scholarship and myriad other activities, working as a dedicated archivist, anthologist, and editor, preserving historical documents such as periodicals and editing the writing of others. And above all, he engaged himself as a witness of history, even as he turned his attention to his own manas in the series of autobiographical writings—Amar Ekattor, Kal Nirabadhi, and Bipula Prithibi. It is apt that the titles of his testimonies refer to Tagore's address to Bangiya Sahitya Parishad—"Not self-interest, not fame; the true end of literature is time endless, and the world, immeasurable"—a vision he carried out in his own life.

It is difficult to think of the Bengali twenty-first century without him, the pillar who outlived many of his generation in order to guide us through the darkest hours of our history. The true end of literature is love and empathy, tolerance and dialogue. It gave all Bengalis a nationalism that transcended borders and ruptures. He ends Swaruper Sandhane with a Shamsur Rahman poem from which I quote a line—"Freedom, you are/the sparkling leaves of an aged banyan tree." The aged banyan tree falls, but the sparkling leaves of his books remain for posterity. As long as we have that, we will continue to have the freedom he valiantly fought for and taught us to value—the freedom of Bangladesh, but also of language, life, and thought.

Ahona Panda is a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Chicago.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments