Breaking chains through whistleblowing

"Julian is free." The headline of Democracy Now! sent shivers up my spine. The news broke, unleashing a wave of chemical messengers in my brain. The system kept the WikiLeaks founder incarcerated for more than a decade. A woman in Sweden accused him in a sexual assault case in 2010, soon after his whistleblowing platform published a report on US military actions in Iraq and Afghanistan. Julian Assange jumped bail and took refuge in London's Ecuador embassy in 2012, seeking political asylum. He lived in a tiny cell in that embassy compound for seven years, during which period the rape charges were found meritless. However, the British government arrested Assange and placed him in the high-security Belmarsh Prison, forcing Ecuador to revoke its asylum decision. The US wanted him extradited on charges of espionage and leaking sensitive documents. The Australian government finally intervened, saying the case had dragged on for too long. Julian Assange is finally free after pleading guilty to one count of espionage. The court determined that he had already served his five-year sentence, given his prolonged imprisonment. Justice is restored.

Why does it matter for us when a foreign individual is free after such a long time? The short answer is: Julian Assange is a symbol of hope, just like Nelson Mandela and Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman were during their imprisonments. What good is symbolism when realpolitik demands much more direct action or intervention when millions are dying? When is "one" more than one? When does a man become many?

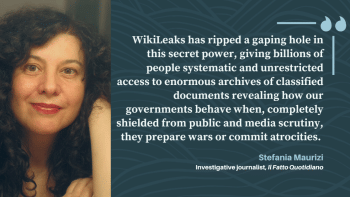

It takes real courageous individuals to blow the whistle and alert the community. WikiLeaks, responsible for what has come to be known as Cablegate, released confidential files on human rights abuse, political machinations, and corruption, leading to a diplomatic fallout and a stringent reassessment of the information gateway. The repercussions faced by Assange are not unique. Character assassination, social ostracisation, and legal battles are some of the known weapons used to castigate whistleblowers. They provoke the system's anger by raising concerns about institutional corruption or moral injustices. Still, they dare to share information to ensure transparency and accountability and become the catalysts for change.

WikiLeaks has brought to light numerous cases of bribery, extortion, corruption, murder, and other crimes committed by Bangladeshis, enabling them to amass a staggering amount of money, which they then syphoned out of the country. And to think that some of our culprits have more money abroad than our foreign exchange reserves speaks volumes about our institutional weaknesses. The whistleblowers' bravado often forces the system to address its leaks. Their bullheadedness gives us hope—a hope that is contagious.

When Bangabandhu was in prison during the Ayub Khan regime, he realised that the whole of East Pakistan was in prison. His obstinacy gave us hope and prepared us for the freedom fight. When millions of refugees displaced by our Liberation War took shelter in India, our country began with the realisation that we could be a poor country, but we needed to be rich in soul. Years later, we witnessed our prime minister providing shelter to hundreds of thousands of Rohingya refugees, reflecting on our common experience of displacement during wartime. The same is true for Mandela, who believed that his struggle for freedom would be incomplete without the freedom of Palestine. Years later, South Africa, inspired by the words of their visionary champion against apartheid, has taken Israel to the International Court of Justice.

Analogously, Assange's freedom can have far-reaching impacts. That makes me hopeful. I listen to Yanis Varoufakis' passionate speech, detailing the background of resistance that conditioned his freedom. The former Greek minister recounts how their allies began abandoning them under the guise of opposing an alleged rapist, despite the later exoneration of the charges. Now that Assange is free, the system will need to undergo numerous adjustments and deal with the consequences. Similar systemic readjustments were required in the political arena after Edward Snowden exposed the National Security Agency's (NSA) mass surveillance programmes. Or when Frances Haugen, a former Facebook employee, exposed her company's harmful practices by leaking internal documents. There are many other instances.

Let me end on a lighter note, though. A hill of corruption collapsed when a goat turned out to be a whistleblower. An animal trader was running a notorious racket, adding pedigree to his stocks to inflate their prices. Like a true trickster, he would boost his clients' egos by creating a false consciousness about his cattle. He would charge a crore for a cow and about Tk 15 lakh for a goat. Somehow, the price of the goat was too much to stomach for the audience. People were curious about the individual who was willing to spend such a significant amount of money on a goat. The goat became the unlikely whistleblower to expose the buyer and his family, who were relishing a mountain of ill-gotten wealth. The drama did not end with an incomplete purchase. The trader who boasted about his animals' pedigree is now on the run, as the whole system has come after him, possibly for exposing one of their own kin. The ordinary public, which lacks decent earnings and livelihoods, enjoys the show as the goat becomes the unsung hero.

I hope there is no connection between the recent announcement of lower loan rate incentives given to goat farming and the practice of goatheadedness as a form of resistance to corruption. It will take more than a goat to break the chains through whistleblowing.

Dr Shamsad Mortuza is professor of English at Dhaka University.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments