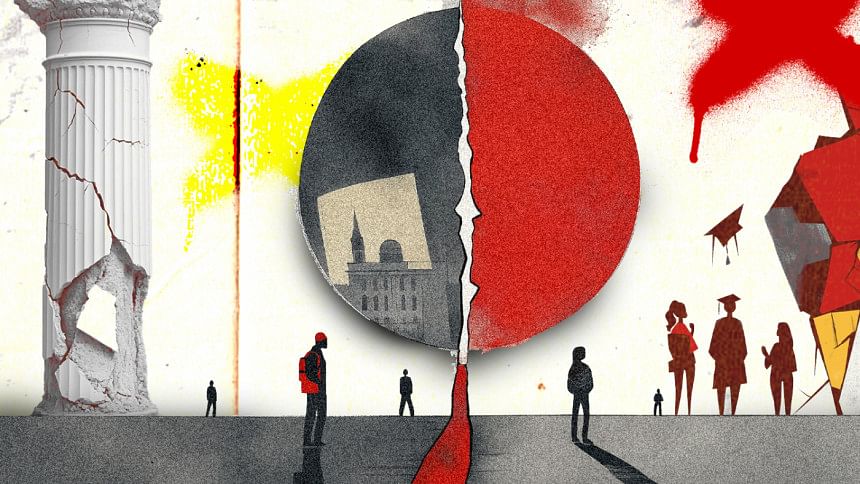

Neoliberal education, student rebellion, and institutional stability

The call for the removal of a private university's vice-chancellor and reconstitution of its board of trustees, following a probationary disciplinary action taken against two students for drawing graffiti on campus, has scratched the surface of the deep-seated wound of our neoliberal education system. The students used an "anti-fascist" banner to express their opposition to the university's actions, which they believed aligned with the previous government's ideology. The presence of sympathisers, or members of the fallen government, on the board made the students interpret the punishment as a politically motivated gesture. They demanded the VC, who ordered the punishment according to the university's code of conduct, be removed.

However, following an appeal by some conscientious faculty members, the university authority rescinded the punishment. That did not stop a section of students under the banner of the "anti-fascist" group from targeting the top management, forwarding a five-point demand and making their protests visible through a fresh flurry of abusive graffiti. When senior officials and faculty members, on behalf of the VC, tried to engage in peaceful dialogue with the protesters, they were restricted from leaving the campus until midnight, with the main entrance blocked.

The captivity of faculty members prompted general students to hold a counter-rally and conduct independent online polls, showing that the majority of the student population supported the continuance of the current leadership. A member of the "anti-fascist" group reacted by adopting a fast-unto-death programme. An emissary from Adviser Nahid Islam arrived at the scene to draft a five-point agreement: i) constitution of a probe body by the University Grants Commission (UGC) or the education ministry and the abstention of the VC from holding regular office until the submission of the fact-finding report; ii) general amnesty for all protesters; iii) delinking any potential political connections with the fascist regime by faculty and staff members; iv) removal of abusive graffiti by the protesters; and v) a note of apology to diffuse the tension.

Since the issue is under investigation, I am not naming the university or the individuals concerned. The stakes here significantly exceed those of a single private institution. If we fail to address the problem, it could lead to a chain reaction destabilising Bangladesh's higher education sector. The adviser's timely intervention signals the importance that the interim government has invested in this issue.

It is undeniable that private university students were instrumental in the July uprising, making significant sacrifices and losing hundreds of their peers in the process. However, their contributions were largely ignored when the interim government was formed. Their frustrations are, therefore, deep and valid. They want to see changes in their respective institutions, reflecting their revolutionary passion. But it is also important to distinguish the inherent differences between the public and private systems.

The Private University Act, 1992, revised in 2010, paved way for private universities to accommodate the growing demand for higher education. Over the last 32 years, more than 100 universities have received permission from the UGC to offer degrees at both undergraduate and graduate levels. In 2022, more than 3.41 lakh students were studying at 106 private universities, taught by 16,508 teachers, according to the 49th UGC Annual Report. These universities are non-profit entities run with tuition fees and endowments from philanthropic and business entities. Meanwhile, taxpayers fully subsidise state-run universities. For instance, in 2022, the state paid, on average, Tk 218,558 for each Dhaka University student, Tk 466,000 for each student at Bangladesh Agricultural University, Tk 314,478 for each student at Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology (BUET), and Tk 144,609 for each student at Chittagong University. One can calculate the amount the state spends on each student who graduates with a four-year degree.

Private universities, in contrast, pursue neoliberal education that prioritises market-driven policies, privatisation, and the commodification of learning. Whether we like it or not, this framework treats education as a product and students as consumers. These institutions have emerged as vital alternatives to overburdened public universities, offering flexible schedules, modern facilities, and diverse academic programmes.

We need to acknowledge that private universities have filled the educational gap through a paid service. They have created opportunities for thousands of students who would have otherwise been forced to seek higher studies abroad. The quality and well-being of these universities need professional supervision and monitoring. It takes decades for an institution to grow and earn a reputation, but only a series of disruptions to tarnish it. Such disruptions often originate from individuals who have personal agendas or lack a clear understanding of the larger picture.

The above-mentioned student rebellion at a private university serves as a prime example. The intertwining of educational institutions with their trustees' political allegiances creates challenges, particularly during periods of political change. Students choose universities for the academic or institutional reputation. People who run the institutions may come from different cultural backgrounds and ideological orientations. In an open market, students and guardians are free to align their political interests with the trustee board members. However, for an institution to be more sustainable, personal ideologies of the board should not impact the institution's activities. Still, if someone believes the institution needs changes, they should voice their concerns at the central level. Monitoring agencies such as the UGC or education ministry should make necessary policy reforms to protect the institution from such individuals. The structure of private universities is different from that of public ones. The stakeholders must recognise the nature of the institutions in which they are participating.

Political affiliations may be held by philanthropic individuals and business houses that typically establish these private universities. These ties have been both a strength and a liability. On the one hand, politically connected trustees can secure resources and navigate bureaucratic hurdles; on the other, such affiliations make institutions vulnerable to regime changes, often targeted by rival factions. Educational institutions are complex systems designed to function independently of their leaders' personal affiliations. While holding individuals accountable for misconduct is essential, targeting them in ways that undermine the institution can have far-reaching consequences.

Destabilising educational institutions in the name of reform poses significant risks to students, faculty, and other stakeholders. For students, prolonged protests and administrative paralysis can lead to academic disruptions, delays in graduation, and increased financial and psychological stress. Faculty members may face uncertainty regarding their positions, while parents and other stakeholders may lose confidence in the institution's ability to deliver quality education.

Destabilisation, on a broader scale, erodes the credibility of private universities, which are already viewed with scepticism by some segments of society. The erosion of trust can have cascading effects, deterring prospective students and investors and compromising the long-term sustainability of these institutions.

To address these challenges, it is imperative to focus on constructive and policy-driven reforms. Students play a crucial role as change agents, but their activism should focus on systemic improvements instead of individual retribution. Key areas for reform include transparent governance, inclusive policymaking, and/or national education policy reforms. And this can be attained through constructive engagement and public discourse.

Dr Shamsad Mortuza is professor of English at Dhaka University.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries, and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our submission guidelines.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments