Living on hope, devoid of reality

Many of us believe and widely practise the cliché of, "Hopefully, this shall not happen to me" – or, more selfishly, "to my family." But merely hoping is often not good enough. The natural instinct of some of us is to ignore the mask-wearing rule even under severe Covid conditions. Those who contracted the dreaded illness had other issues, they argue. Just blow your nose in the morning and you are good for the day. In fact, you don't need the vaccine, either. My quoted friend, who did both, died from the disease.

We feel safe leapfrogging across a busy road after acrobatically scaling or going underneath the road divider – and not even in our sports gear – thinking, "The dead were not watching the traffic like I do." Others reassure themselves, "Drivers have eyes and brakes, don't they?"

We feel confident to construct six more floors above a building which has a foundation meant for a three-storey structure. Since, out of thousands of cases, only two such buildings (dishonestly vertically extended) have collapsed, we dare to profit from illegal ventures. Regulatory agencies, manned by real people, are also visually constricted during years of construction by fiscal benefits, naughty people say.

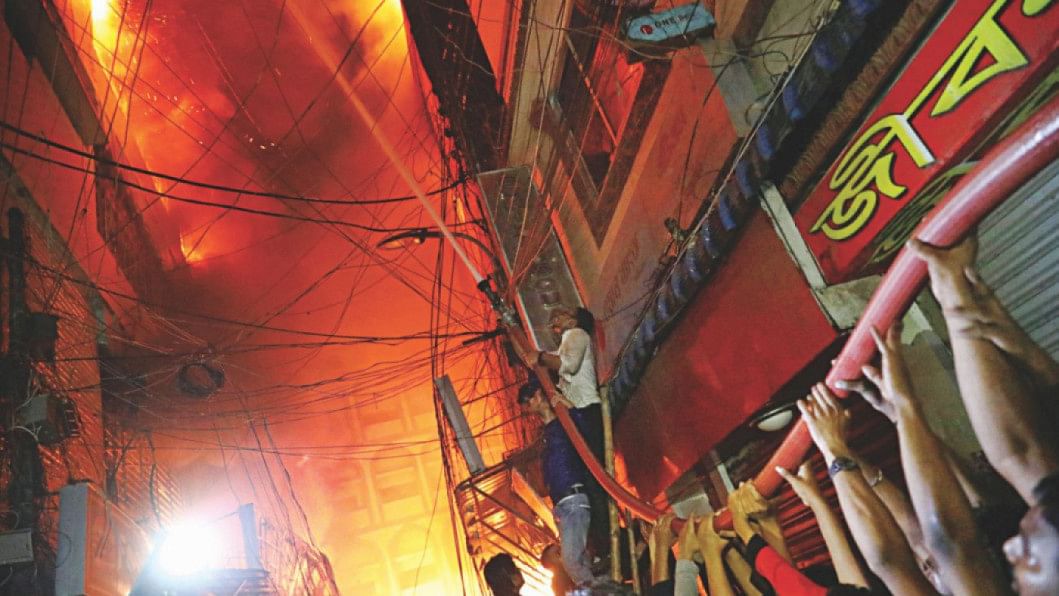

"Lightning does not strike in the same place twice" seems to be the philosophy behind storing explosive and flammable chemicals. The hazard is so profitable that deaths appear justified. Tragedies at Dhaka's Nimtoli (in 2010) and Churihatta (in 2019) areas are a result of greed, not poverty. Before they can say, "This cannot happen here, because we are very careful," boom!

We risk the lives of the sick, too. Some of our hospitals are in such narrow buildings that there is zero possibility of lateral movement, and they are several storeys high with only one staircase. Means of escape are non-existent. The fire code requires bedded (immobile) patients to be moved across two doors into a safe room. There is none. After a fire, there will be none.

The rashness and downright stupidity of unqualified people offering medical disservices is another ultimate. Treatment is proffered by technicians or lesser mortals. We can hardly blame their patients, for that is the latter's best option in terms of affordability. The business attitude of proprietors of these kangaroo hospitals is: "A few would die anyway, today or tomorrow." Even Aristotle dared not propound such a bizarre philosophy.

Quite needlessly, one may say, five innocent lives were lost when a crane driver's assistant, unqualified and without a licence, was given the key to move a girder. They were probably thinking, if at all, "What could possibly happen? It's only a concrete mass that might just crush only one of the many cars that ply on that section. A safety barrier will inconvenience so many people. Tch, tch! Life must go on." That is technology laced with bravery.

About how an anari helper was allowed the control of the crane, and more crucial questions, there are inquiries going on. No country in the world has as many incomplete, deferred, unread, forgotten and buried inquiries as ours. After some time passes, we have a knack to be soft on crime or the artistry to muddle up the facts. As if we are playing endless computer games. But, in life, there is no clandestine voice sombrely assuring, "You are dead. You have eight lives left."

Common sense, awareness, education, training, information update, implementation of a well thought out programme, and humbly learning lessons are important steps, albeit in varying degrees, in assuming and carrying out one's responsibility at any level of a real job. That applies to both individuals and members of a group or agency. Sloppiness or a slip at any link in the chain can, will and does spell anything from trouble to disaster.

Since human lives and valuable properties are concerned, it is crucial that government agencies wake up to their call of duty. Lack of manpower and other resources is an oft-abused excuse. You have to catch a few and impose a suitable penalty; the rest will fall in line. Instances where mobile courts penalise clinics, restaurants and hoarders are encouraging examples. Seatbelts for drivers and front-seat passengers were ensured by our police by imposing a few fines.

Our so-called daredevil gallantry, however, disappears when telling off corrupt politicians, businesspeople and civil servants. But more about that another day.

Dr Nizamuddin Ahmed is an architect and a professor, a Commonwealth scholar and a fellow, Woodbadger scout leader, Baden-Powell fellow, and a Major Donor Rotarian.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments