Bracing for another storm

The boon of knowing the cyclone was going to miss the southern tip of the country and barrel towards our neighbour has the bane of a premonition: next time we may not be lucky. Alongside the coastal town of Cox's Bazar, at least two of our major islands in the Teknaf range faced the full blast of the storm surges whipped by Cyclone Mocha, which made landfall on the coast of Myanmar's Rakhine state on May 14. Cox's Bazar, which shares the stretched beach with Sittwe, the capital of Rakhine, was lashed by the gigantic beast that rose from the deep. With horror, we witnessed the cry for help from St Martin's Island and Shah Porir Dwip. Luckily for us, the storm weakened rapidly after reaching the shore and the damage to lives was minimal.

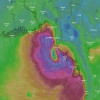

Technology helped us remain updated on every fine detail of the disaster. The easy availability of satellite images allowed us to track the movement of the cyclone. For almost a week, we kept an eye on the eye of the whirlpool to pray, "Oh dear God, let the sea monster not see us." Our ancestors did not have the luxury of technology to fathom the cause of natural calamities. They would rather use their imagination to explain natural phenomena in supernatural terms. With their imagination, they would populate the world with various mythical or legendary figures. Fear would be personified as an overwhelming beast finding its place in a narrative plot. Godzilla, rising up from the Pacific as a symbol of a tsunami, is a classic example.

In all littoral cultures, sea creatures are associated with natural phenomena. Maldives is a good example. As the Medhu Ziyaaraiy Shrine in Malé would tell you, an Arab trader in the 12th century saved the country from a monster called Rannamari, who would require the sacrifice of a maiden every month. Abu Yusuf, a castaway sailor who found refuge on the island, volunteered to face the monster in place of his rescuer's daughter. He kept on reciting from the Quran, which kept the monster at bay. The Buddhist king promised that he would convert his entire kingdom into an Islamic one if Yusuf could get rid of the monster. Legend has it, Yusuf was successful, and the Maldives changed.

This anecdote of mass conversion made me reflect on the psychological impact of disasters on those who experience them. A video clip from a livestream on Facebook from St Martin's Island showed how women and children were struggling to climb down the stairs of a shelter home whose roofs were torn by the gale force. The blast of wind and water took me back to a childhood memory of being stranded in an open field somewhere in Khulna during a nor'wester. We were in an open Jeep with a makeshift plastic cover. The rain blades ripped through the plastic sheet and hit my cheek. The flashback of that traumatic experience still haunts me 40 years later.

So I wondered, how do these people who experienced all these cyclones negotiate with these traumas? Is there any official policy in our disaster management handbook to measure, monitor, and care for people with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) following natural disasters? My cursory search revealed a few references. Yet, we are a country born out of the aftermath of the 1970 cyclone. The results of the national election gained uber-nationalist fervour as the people of the erstwhile East Pakistan realised how indifferent and inhuman the central rulers were. The storm severed whatever semblance of ties we had until then.

Indeed, we are much more prepared to deal with natural disasters in our own independent country. It was heartening to see our emergency servicemen reach out to the people in distress. Such rapid response is restricted to physical damages. But I am afraid that the long-lasting impacts of natural disasters are largely ignored.

Victims of a natural disaster can develop PTSD not only through the degree of physical injury they suffer, but also through the immediate risks they face. The experience of losing family members or property, relocation or migration following a natural event can put victims at a higher risk of developing PTSD. In India, psychosocial services were incorporated into their policy framework after Cyclone Fani. Mohammad Budrudzaman, a field researcher writing for The Third Pole, observed that there was no such policy in our national agenda.

The appearance and disappearance of a cyclonic storm will perhaps add to our image of being a resilient nation. But the strong public image that we want to carry often denies the emotional damage caused by disasters. There are two instincts of life (Eros) and of death (Thanatos) in us, if I may suborn Freud. Faced with trauma, some of us would find ways to survive and celebrate life, while there will be others who will keep on reliving the trauma and can even self-annihilate. There were reports that the island dwellers refused to be relocated before the storm, showing that they did not take the warnings seriously. Their memories of negating and negotiating previous storms probably made them take extra risks. The same goes for the disaster tourists who went to the beach to witness the full blow of the cyclone for a few more likes on Facebook. These are all case studies.

If my Google search on the psychological impact of disasters in Bangladesh is to be trusted, then there is hardly enough research on the links between mental health and environmental stressors exacerbated by natural disasters. Our actions and reactions to Cyclone Mocha suggest that we need a thorough scanning of our national psyche to understand how we approach future storms and offer psychosocial after-services.

Dr Shamsad Mortuza is a professor of English at Dhaka University.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments