Contraception use in Bangladesh: From revolution to stagnation

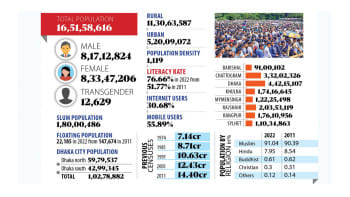

Bangladesh is often cited as a model for developing countries aiming to build strong family planning programmes, and with good reason. The country has had one of the strongest and most successful national family planning initiatives in the world, increasing its contraceptive prevalence from only 7.7 percent in 1971 to 48 percent in 2004 – a 40 percent increase in 33 years. This undoubtedly helped lay the groundwork for Bangladesh's impressive success in improving maternal and child health, as evidenced by the decline in the total fertility rate from 6.87 to 2.14 per woman and the decrease in maternal mortality rate from 570 to 173 per 100,000 live births during this time.

However, Bangladesh's progress has recently stagnated. Over the last 19 years (from 2004 to 2022), the country's contraception use has increased only by six percentage points – from 48 percent to 54 percent. The unmet need for contraception has remained constant at 12 percent since the early 2000s. Long acting and permanent methods (LAPMs), including female sterilisation, intrauterine devices (IUDs), and implants, remain very low at eight percent, and this rate has not changed significantly over the decades.

Poor and rural populations are particularly marginalised in terms of access to contraception. As a result of this stagnation, Bangladesh has failed to meet the commitments it made in the 2012 London Summit on Family Planning, including increasing contraceptive use to 75 percent by 2021 and improving the choice and availability of LAPMs. Now this stagnation poses a challenge for Bangladesh to attain the universal coverage of contraception use, a target set in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Meeting this target is regarded as important to achieving other SDGs targets, including maternal (reduce to 70 per 10,000 live births) and child (reduce under-five and neonatal mortality to 25 and 12 per 1,000 live births, respectively) mortality reduction. Progress over these targets has also been slow in recent years.

One possible reason for this stagnation is the higher prevalence of unintended pregnancy (around 47 percent) due to lack of contraception, particularly LAPMs. It has several adverse consequences, such as unsafe abortion, which alone accounts for 13 percent of total maternal deaths in Bangladesh. Additionally, unintended pregnancy leads to lower utilisation of maternal healthcare services, which is observed in the cases of one-fourth of the total live births in Bangladesh that were unintended at conception. This lack of healthcare service use ultimately leads to higher pregnancy complications and higher maternal and child mortality rates.

This stagnation, which follows a period of great success, is largely due to reduced exposure to family planning messages and a devaluation of the contraception distribution process. Exposure to family planning messages, for example, decreased from 44 percent in 2004 to approximately 22 percent in 2018, despite government targets to provide family planning counselling and contraception at the field level, as was done before the 2000s.

The reduction in exposure to family planning messages can be attributed to two main reasons. First, Bangladesh has made significant progress in women's education and their participation in formal work, which means that they are less available at home compared to the 2000s. This shift in women's roles and responsibilities has made the previous approach of providing family planning and contraception through visits by family welfare assistants (FWAs) no longer effective for many women, even if they intend to use contraception. Second, the current number of posts for FWAs is inadequate, as it was created in the 1980s when the population of Bangladesh was around half of what it is now, and around half of the available posts are vacant. Consequently, while the provision of family planning services at the household level remains functional, there appears to be less enthusiasm than it was during the 2000s, resulting in lower quality of services and fewer visits. The lack of governmental monitoring also exacerbates the problem.

Poor and rural populations are particularly marginalised in terms of access to contraception. As a result of this stagnation, Bangladesh has failed to meet the commitments it made in the 2012 London Summit on Family Planning, including increasing contraceptive use to 75 percent by 2021 and improving the choice and availability of LAPMs. Now this stagnation poses a challenge for Bangladesh to attain the universal coverage of contraception use, a target set in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Since the early 2000s, contraception has been distributed from healthcare facilities in addition to the previous approach of distribution at the field level through FWA visits. This transformation sends a message to the FWAs that contraception is available at the nearest healthcare facility, and women should collect it from there if they want to. This may motivate the FWAs to reduce their focus on contraception at the field level and give more attention to their other duties, including child vaccination. Moreover, contraception is considered culturally sensitive in Bangladesh and requires privacy for providers to discuss, although facilities rarely have private corners. Furthermore, the provision of joint services makes health centres overcrowded. As a result, healthcare workers, for whom providing maternal healthcare is a priority, do not have enough time to discuss contraception and counselling services. Even if they have the time, they often do not feel comfortable providing family planning services and contraception with an MBBS degree. Additionally, there is little to no coordination between services being provided at the household level and health centres. Such uncoordinated delivery results in unequal coverage, and some people may miss out on services. Together, these indicate system-level challenges to contraceptive uptake.

These challenges are often exacerbated by the lack of sustainability of the relevant policies and programmes formulated by the government. For instance, the government's plan to include men in family planning services and focus more on LAPMs is mostly not implemented at the field level. Before 2008, the operation of over 18,000 community clinics was stopped because they were established by a previous government, without considering the effects at the field level. Along with these challenges, the current achievement of replacement-level fertility should motivate the government to reduce its focus on contraception at the field level and give more attention to population management.

Whatever the challenges or intentions are, it is important to ensure universal coverage of contraception. This is not only to achieve the SDG targets, but also to give women in Bangladesh a chance to control their own fertility and plan their families, which in turn contributes to the reduction of maternal and child mortality.

Dr Md Nuruzzaman Khan is a public health expert and assistant professor of population science at Jatiya Kabi Kazi Nazrul Islam University.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments