DAP density control plans will make housing even less affordable for the poor

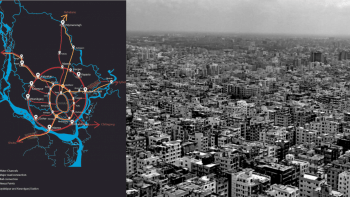

A city as large as Dhaka cannot have just one detailed plan for all its areas. It should, instead, plan the expanding and newly claimed areas that are inevitably surrendering to urban use, especially in terms of informal settlements lacking in infrastructure and amenities, irrespective of rules and regulations.

However, the recent Detailed Area Plan (DAP) for Dhaka has no plans for its 18 central sub-areas and eight expanding sub-areas, even though sub-areas should have detailed plans showing its permissible uses, types of developments, amenity locations, and right of way for transportation. The DAP could also plan already-planned areas, the uses of which have deviated, diversified or intensified, such as Tejgaon or Motijheel.

Of the many policies and strategies in DAP, density control (which involves building fewer houses) has been highly contested. Urban density, referring to the number of people inhabiting a given urbanised area, does not only refer to residential areas but looks at a broader spectrum. It describes urban phenomena, and different phenomena can result from the same density. Thus, it hides more than it reveals – examples include overcrowding,high plot coverage, ghost cities, and large apartments with low ground coverage and small residential shares. None of these can be justified for a city like Dhaka.

In the current DAP, the meaning of "density" is missing. Is it the volume, building heights, or the numbers of people? One person's high density may be another's sprawl; the same tall building may be oppressive or exhilarating; a "good crowd" for one can be "overcrowded" for another. Population densities vary, as the numbers of people in a neighbourhood at a given time include those who work there or are visiting, making the same precinct dense during work hours and empty on weekends. Density fluctuates with functionality. In mixed-use neighbourhoods, residents are not alone; people move from place to place, creating density rhythms.

Urban density is important for a city's functions. A 2020 study concluded that density boosts productivity and innovation, improves access to services, reduces typical travel distances, encourages energy efficient construction and transport, and allows amenity sharing. There is also the complexity of street-life density of jobs and visitors, functional mix, car dependency, mobility and walkability. What is often overlooked is that an urban "buzz" can deliver huge socio-economic benefits. Therefore, many planners advocate higher densities, as cities operate more efficiently when residents live closer.

Sustainability has many components relevant to planners, the most important being how people move around. Dense cities have greater options. Cities lack sustainability and quality of life if they expand without smart planning and depend on cars as the primary mode of transport. This generates sprawl characterised by road-dependent developments, increased air pollution, and expensive municipal services (cheaper only in dense, multi-functional developments).

Much of urban planning theory has been premised on raising densities along with new urbanism, smart growth, transit-oriented development, etc. All these, except densification, have been considered in the new DAP, even though urban experts argue that low-density dispersed car-dependent cities are unsustainable, and high-density cities are more efficient.

The DAP also presumes that the city cannot provide utilities to the projected population of 31 million in 2035. Both of these are contentious ideas. It is the main planning objective, as well as the authorities' responsibility and citizens' right, that the government provide all basic necessities – they cannot be denied on the premise of incapacity. This should have been established at the Structure Plan level. Urban area plans under it should list strategies to implement policy, and the DAP should show how they can be implemented at the local level.

Both the 1981 and 1995 Plans suggested the densification of Dhaka, as more people could be accommodated within its conurbation with existing infrastructure. Floor area ratio (FAR), the commonest measure of density, and the number of dwelling units, have to be viewed in conjunction with ground coverage, unit size, family size, residential density, employment density, etc.

With the same FAR, it is possible to build high-rise low-density buildings, or low-rise high-density ones. Building height is not a measure of density, although sometimes the two align. However, confusions abound here, since the current DAP is equating FAR with dwellings/acres to control population, a blunt measure that neither assesses population nor building densities, unless the sizes of dwellings and households are defined.

The greatest fallacy of the DAP's philosophy – building less houses – cannot deter in-migration; all literature on the topic suggest it will encourage informal settlements, urban sprawl and the filling up of water bodies. People come to the city for predominantly economic reasons, and a majority of them resort to informal settlements or bostis. Only a national socio-economic plan can ensure a situation to prevent this, which is beyond the scope of the DAP or Structure Plan. Various modelling suggest that Dhaka could become a city of 31 million people by 2035. Add to it the climate migrants created by sea level rise and other calamities. Southern Bangladesh being the most vulnerable in this regard, there will be a few million extra destitute people in Dhaka by then.

Dhaka's bostis can have deplorable and unacceptable conditions. Yet, we cannot remove them without providing humane solutions, and eradicating the conditions that force such degradation. Unfortunately, the DAP refused to even recognise the term "slum", saying it is "controversial", and that it "wished" for the development of "affordable housing".

The question is, affordable by whom? Readers can recall the gentrification of Bhashantek as part of a government project to build houses for urban slum dwellers, which ended up pushing most of them out from the area since they could no longer afford the housing there.

At the end of the day, the ill-conceived plan for limiting Dhaka's population will ultimately be devastating for the urban scenario of Bangladesh, as well as the socioeconomic situation of a large portion of the population.

Prof Mohammed Mahbubur Rahman is an architect, urban planner and Pro-VC of Ahsanullah University of Science and Technology

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments