The Detailed Area Plan for Dhaka is almost alright

For a city as complex and concatenated as Dhaka, with its multifarious tugs and tussles, the Detailed Area Plan (DAP) 2022-35 produced by Rajdhani Unnayan Kartripakkha (Rajuk) is a comprehensive document unlike any other prepared for the city's planning. The DAP document provokes us to imagine a new city – a Dhaka we are yet to experience. And this may appear incredulous to many, considering Rajuk's poor track record in planning and managing this city.

What I highlight in this article are certain aspects that are neither foregrounded in the document itself, nor engaged in discussions of it. I continue to hold the opinion that those underrated aspects are actually radical opportunities for Dhaka's transformation. The DAP propositions need to be more progressive, and not watered down. It is in that sense I use the term "almost" in the title of this article (adapted from American architect Robert Venturi's famous essay "Main Street is Almost Alright").

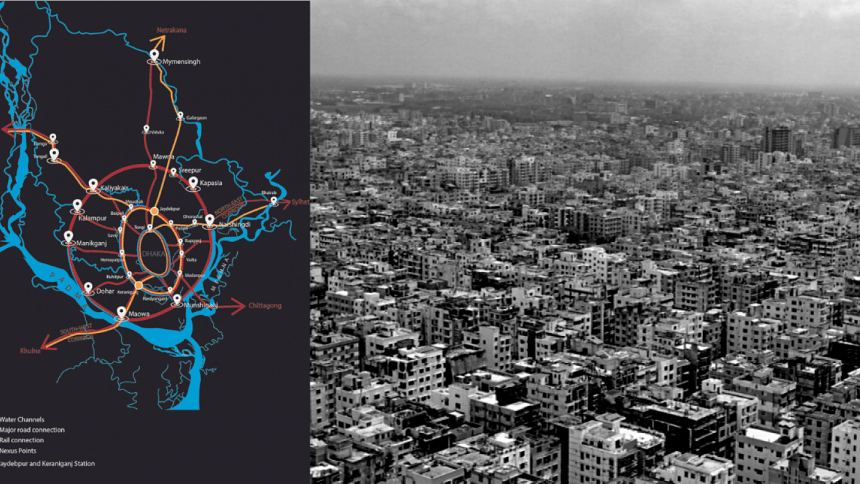

One striking aspect of the DAP document is the geographical scope of Rajuk, in how it signals an expanded Dhaka. Within Rajuk's jurisdiction, areas for the two city corporations are denoted as "central region," the familiar identity of the city. Even when there are two more major city corporations (Narayanganj and Gazipur), and a few other municipalities and upazilas, the central region (one-sixth of the total Rajuk area) enjoys a privilege in the imagination of Dhaka. The new DAP has brought to light that the Rajuk jurisdiction is not constituted any more by what we have always known as the very built-up central region. In fact, the jurisdiction includes villages, floodplains, agricultural areas, and unevenly developed areas, and the other city corporations and municipalities.

A new city imagination is now possible in which the central region can be decentred by leveraging the vast area beyond it. With the Mass Rapid Transit (MRT) and Bus Rapid Transit (BRT), there should be more leverage for a better distribution of cityness throughout the Rajuk region. If selected areas in Gazipur, Savar, and Keraniganj develop as brand new fabrics with all urban facilities, and not just reproduction of typical developments, there will be a greater equity in diversity, and a good-quality living could spread throughout greater Dhaka.

What is also implied above is a formidable topic in 20th- and 21st-century planning – the making of neighbourhoods. The DAP document emphasises area and neighbourhood planning with a schema for Rayerbazar. Neighbourhood is the social aggregation of urban form, and not merely administrative wards or unions. We have lost the sense of what used to be neighbourhoods or mohollas in this city. Certainly, this is a complex topic, but one reason neighbourhoods have eroded is because of the ferocious attachment to plots and real estate speculations that developed since the 1980s. In this city, instead of planning comprehensive urban forms, we have always planned from the plot and not the other way around.

The transit-oriented development (TOD) offers another opportunity for creating concentrated urban hubs or neighbourhoods. Considering the upcoming MRT and BRT systems, TOD is a perfect opportunity for radically restructuring Dhaka. MRT is not only a transport artery, but an urban development strategy in which each station becomes a new hub of intense assembly and activities, and the transit line a development corridor. DAP does mention a 200m and 500m diameter of influence zones around the stations, but what is required is a detailed plan of those encircled areas, similar to the Rayerbazar schema. I would suggest the MRT and TOD planners look at Tokyo and Bangkok, and in any future revision of DAP, consider higher floor area ratio (FAR) for an area around the stations and along the artery. With taller mixed-use buildings around the stations, high density habitats will ease commuting time and create greater ridership and a sustainable situation.

Dhaka dearly needs a walkability plan. Walkability is key to creating a neighbourhood quality and a humane city. If 40 percent of the people walk as part of the overall transport movement, Dhaka needs a walkability infrastructure in which footpaths take centre stage in the movement system. A walking infrastructure is critical to the success of MRT and BRT lines. It is expected, as is the case for any city with successful mass transit, that people will access the stations by walking, not by driving there.

Another key topic in the realisation of a better and equitable Dhaka is housing. By housing, we mean the production of diverse dwelling units organised as a collective ensemble catering to the various economies of the city, especially the lower- and lower-middle-income groups. What many developers claim as housing is really a summation of dwelling units without impacting the collective, benefiting primarily the middle- and higher-middle-income groups.

What Dhaka then needs are consolidated housing, social housing, affordable housing, and group housing. None of these resonate in the vocabulary of Dhaka's builders, including government agencies, private developers, architects and planners. What the DAP has presented as "block housing" – very importantly – is a precursor to the formation of above housing typologies. An understanding of each of these categories is necessary to translate into policy terms and production process. Again, none of the discussions on DAP is giving this topic the attention that it needs.

But by far, the most debatable topic about DAP is FAR – the number that dictates how much one can build on a plot of land. An Achilles heel for DAP, FAR seems to have no unanimity among the various voices. It appears that the old FAR rules have not produced a good city, and the differentiated FAR in the new DAP – different for different areas based on density and infrastructure – remains under scrutiny. Generally a mechanism for controlling construction volume, the new FAR system is based on the existing density of an area and its projection, existing roads and common services, the character of the area, and, where applicable, proximity to mass transit. The DAP claims the new FAR as a mechanism for the management of population density. However, an argument is made that the differentiated FAR is a recipe for inequity and discrimination.

Critics of the new FAR have mounted formidable arguments: why should Area A have a FAR of 5.1 and Area B 2.0? Does this not infringe on the right to build and develop, and make profit? Considering that the "right" to profit has become naturalised and prioritised in the practices of this city, it is also not "natural" that one can build anything anywhere at the price of liveability. Why should one area have less FAR because of poor facilities? Why not provide facilities first, then? Priority should be how swiftly a better quality of life can be arranged, whether by density management or services. Will density control have an adverse effect on the dynamic of the city, on its future growth? Not if concentrations of new urban hubs are generated in selected areas within and beyond Rajuk.

Based on previous policies and FAR rules, Dhaka remains caught up in the architecture of the (small) plot. The small plot schema may have generated profit for landowners and developers, but it has hardly yielded well-being for the community, and far less for the overall city.

Instead of an architecture of plots, the new DAP document recommends an architecture of the larger scale. There should be now the architecture of an area, the architecture of neighbourhoods, and as the renowned Italian architect Aldo Rossi described, an "architecture of the city." It is obvious that plot-owners and developers from their myopic position cannot be expected to be concerned about the collective. This is where the responsibility of a city agency – top-down, if you will – comes in. Someone has to take charge of the overall, the collective, and the comprehensive scope of the future of Dhaka.

Kazi Khaleed Ashraf is an architect and urbanist, and directs the Bengal Institute for Architecture, Landscapes and Settlements.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments