Do we still follow what our language veterans fought for?

What does the word "Bangla" mean? It means either i) the sum total of all the dialects spoken in the Bangla-speaking areas, including Bangladesh, West Bengal, Assam, and Tripura – an umbrella term for all these dialects; or ii) the Standard Dialect of Bangla (hereinafter SDB), a language of the Indo-European family used in the areas mentioned above.

I am a so-called native speaker of Chittagonian, the easternmost dialect of Bangla, and I learnt SDB at school. Most Bangalees, like me, competently speak dialects like Sylheti, Dhakaiya, etc, and usually speak SDB with a local accent. Bangla or Chittagonian – which dialect is my mother tongue? What is the difference between a dialect and a language? Such popular questions or issues need to be handled in politics, not in linguistics. It is said that a dialect that is supported by an army becomes a language, and a dialect that lacks such an army remains a dialect forever.

Ideas like "mother tongue" and "native speaker" have long been proven to be myths (like ether in physics). One is either a learner or a speaker of a dialect, and no two speakers excel equally in the dialect they speak. Some speakers, usually writers, excel more than others in using their language(s).

Bangladesh, a former British colony, inherited English as its official language. English nowadays is the most widely used lingua franca, and, therefore, we must put emphasis on learning this language. Unfortunately, neither during the Pakistani era nor since the independence of Bangladesh have the authorities been able to decide upon the status of Bangla and English in this country. As a result, Bangladesh does not have a language policy yet.

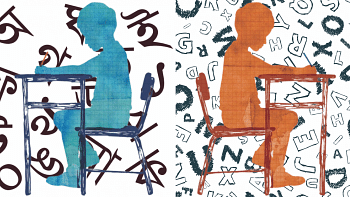

As Bangla is spoken and understood by all the citizens of Bangladesh, using Bangla as the one and only vehicle of communication in administration, courts or business would be optimal. If we want to attain a hundred percent literacy rate, using Bangla as the only medium of instruction at the primary and secondary levels is commendable.

Rather than using English as the medium of instruction, it can be taught and learnt as a language like French or Chinese. English needs to be taught at primary and secondary levels for two reasons: i) English is the means of communication with the outside world, and ii) English may be needed in higher education, because it is one of the lingua academica of our time.

Ethnic minority children should receive part of their primary education in their respective languages. As citizens of Bangladesh, a predominantly Bangla-speaking nation-state, they have to learn Bangla and obviously English. Subjects like literature and history may be taught in native languages, whereas subjects like maths and science can be taught in Bangla or in English.

We may teach English in schools, but we cannot expect Bangladesh to ever become an English-speaking nation. There are natural constraints to learning English in Bangladesh. Children who are born and brought up in this country hardly receive any input in English. English teachers at school or college do not usually speak proper English; in fact, they teach English with an accented Bangla. Despite receiving comparatively more inputs from the SDB, very few can speak this dialect with a proper accent. If the authorities dream of making English the medium of instruction, the project will be dumped.

What is meant by an official language? It's the dialect used as the medium of communication at the court, in the administration, in media, in educational institutions as well as in commerce. Unfortunately, in Bangladesh, verdicts given in Bangla are still rare. Private universities claim with much pride that their medium of instruction is English. Even Dhaka University, which is known for having led the Language Movement in the 1950s, prefers English as its medium of instruction and communication.

Nowadays, Bangla is outrun by English in every sphere of life. Even invitation cards for birthdays or marriage ceremonies are written in English. Signboards and billboards are overflooded with English jargon. We often see people in the media who can hardly utter a sentence without encrusting English words onto it. Government institutions (such as BGB or Teletalk) and regional cricket teams are all named in English. All these indices point to the fact that Bengali is not the de facto official language of Bangladesh, although it is the de jure one.

The ultimate goal of the Language Movement (1947-1952) was to compel the authorities to recognise Bangla, the mother tongue of the majority, as one of the official languages of Pakistan. The reason behind the movement was exclusively economic. Had any language other than Bangla become the de facto official language of Pakistan, Bangalees would lag behind in competition with other nations, and this would hinder them in the long run in their sustainable development.

International Mother Language Day is definitely a misnomer for February 21, because the then Pakistani authorities did not deny our right to speak our so-called mother language. What they did, in fact, and what nation-states often try to do is not recognise a particular mother tongue as one of the official languages of the state. Although language veterans, including Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, knew exactly what they were fighting for, we, the beneficiaries of their toil, out of a little bit of whim and a lot of show-offs, have completely forgotten the true significance of February 21.

Quebec, the French-speaking province of Canada, has been suffering from linguistic discrimination for decades. It adopted a language law in the 1970s, known as Law 101, by dint of which an autonomous Language Commission, answerable exclusively to the governor-general, was established. The language commissioner, with its language offices situated in different cities of the province, minutely protected the interest of the French language in the educational, legal, administrative, and business sector, and as a consequence, French soon became the de facto official language of Canada along with English.

As with most issues in Bangladesh, the question of language has never been handled with enough care and wisdom. Each year, during the month of February, a considerable amount of crocodile tears is shed for the Bangla language. But since the very first day of March, washing its hands (like Pontius Pilate after pronouncing the death sentence to Jesus), our beloved nation marches in a completely opposite direction.

Dr Shishir Bhattacharja is professor at the Institute of Modern Languages, Dhaka University.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments