Forget the coronation, let’s talk about colonialism

This week, the coronation of the British monarch went ahead with all its pomp and pageantry, despite skyrocketing energy prices and an ongoing cost of living crisis in the UK. However, the cracks in the fairytale of a people united in swearing allegiance to their new king – described as a "chorus of millions" – could be clearly seen in the anti-monarchy protests across the country. While neighbourhoods organised street parties to celebrate, others showed their disdain in uniquely British ways – my favourite being an entire stadium of Celtic fans in Glasgow chanting "you can shove the coronation up your…." (I leave the rest to your imagination) during a football match.

Polls conducted by YouGov suggest that while there is still considerable national support for the monarchy, it is currently at the lowest it has ever been, especially amongst younger generations. It also showed that 38 percent of ethnic minority Britons supported the monarchy, 39 percent were against it, while another 23 percent were indifferent.

It should come as no surprise that minorities, many of whom have roots in former colonies, should have complicated feelings towards the monarchy. While loyalists will point towards the fact that this coronation took special care to include representatives from different groups in the UK, including Muslims, Jews, Sikhs, and Hindus, it's hard to forget the media attention the royals have received in recent years over their (alleged) racial prejudices.

It is even more difficult to separate the British monarchy from the legacy of the British empire, where so many atrocities were committed in the name of the king/queen and country. And even though the consequences of empire can be felt to this day – in remnants of resource plunder, arbitrarily drawn borders, and colonial-era laws, to name a few – a collective amnesia seems to have settled on all of us regarding these historic injustices.

In recent years, however, the UK has finally started to move towards a public reckoning of its past, especially after the dramatic toppling of the statue of slaver Edward Colston in Bristol in 2020. A number of organisations, universities, and local councils launched inquiries into their historical connections with slavery, and have promised some form of restorative justice. For example, after finding out it had benefitted financially from Scottish slave-traders in the 18th and 19th centuries, Glasgow University set up a joint centre with the University of West Indies and pledged GBP 20 million – the first British university to do so.

This mainstreaming of a long-overdue conversation about the worst evils of empire is largely thanks to the ongoing work of a number of Black academics, journalists, and activists, and their allies. In recent months, The Guardian also published a fascinating series on the links between Britain's cotton industry (and wider economic development) and the Transatlantic slave trade, at a time when slavery had technically been "abolished" in the UK, heavily informed by research from Caribbean, Black-British, and African-American academics.

Even Buckingham Palace has voiced its support for a research project investigating the monarchy's involvement with the slave trade. Whether this is the first genuine step from a regressive institution to come to terms with its past, or a more pragmatic response to the threat of Caribbean countries following Barbados' lead and getting rid of the British monarch as their head of state, only time will tell.

To my knowledge, the only formal apology ever issued came from Queen Elizabeth II to New Zealand's Maori population in 1995 for the atrocities and land theft committed against them in the name of Queen Victoria. Interestingly, she never responded to calls to apologise for atrocities committed in her name, such as the brutal suppression of the Mau Mau rebellion in Kenya.

Only last month, PM Rishi Sunak said in parliament that "trying to unpick our history is not the right way forward", while Home Secretary Suella Braverman has publicly boasted of being "a fan of the British empire." Their statements reflect the British empire's most lasting and resounding victory: the unique handicap of the colonised mind.

Nevertheless, a call for reparations, apologies, or some sort of acknowledgement of Britain's colonial past, including the return of stolen artefacts, has been raised by a number of countries, especially in Africa and the Caribbean. Both from within and outside, the UK is being asked to address the wrongs of its past.

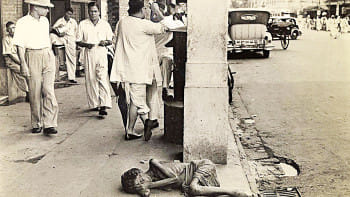

However, it seems to me that countries formerly part of British India, and their descendants within the UK, are playing an ambivalent role in this discussion. While there were calls for a formal apology on the 100th anniversary of the Jallianwala massacre, and the Kohinoor diamond remains a popular topic of debate, there seems to be little push to account for the unprecedented loss of life during the Bengal famines, despite research that argues the 1943 famine was a direct result of British war-time policy.

We know about the the brutal suppression of peasant revolts in Bengal, the execution of revolutionaries, the violence of Partition from oral histories, our poetry and novels, and more recently from academic writings. But perhaps nowhere was the empire's divide-and-conquer policy more effective than in South Asia, and continued regional tensions – as well as an overall disinterest in memorialising our collective history – make it unlikely for us to come together and create our own movement for justice. In Bangladesh, there has been almost no push to preserve pre-1971 history, while the Indian administration has embarked on a journey to reshape history to suit its needs.

Most embarrassing of all, having a British-South Asian in the highest office in the UK seems to have made no difference at all. In fact, only last month, PM Rishi Sunak said in parliament that "trying to unpick our history is not the right way forward", while Home Secretary Suella Braverman has publicly boasted of being "a fan of the British empire."

Their statements reflect the British empire's most lasting and resounding victory: the unique handicap of the colonised mind.

Thomas Macaulay, when arguing for the importance of English education in colonial India, famously said, "…a single shelf of a good European library was worth the whole native literature of India and Arabia."

This sense of English racial and cultural superiority was an intrinsic part of the British empire and monarchy of the time. Almost 200 years after this statement, how utterly depressing it is now to see British conservative politicians of South Asian heritage stand up in parliament and regurgitate this same tone of superiority to argue for anti-immigrant, right-wing policies.

While they may not be representative of British minorities as a whole, they are certainly the most prominent. And unfortunately, their blase attitude towards the atrocities committed by the British empire may likely be the biggest obstacle in the way of the campaign for justice – not just for South Asia, but for all the descendants of the enslaved and the colonised.

Shuprova Tasneem is a journalist. Her Twitter handle is@ShuprovaTasneem.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments