How we assess education matters

The nature of competition in the education system, something manifested in the way we assess students, can be fatal unless we make a crucial distinction. When we test children in school, we end up ranking them against each other, thereby making the competition to be between children. This is where the flaw lies, as the competition aspect of educational assessment is meant for students to be ranked against their own prior achievement, not against their classmates.

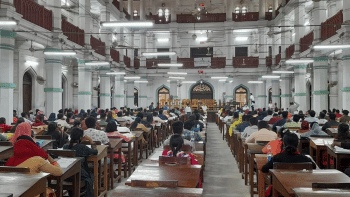

The purpose of assessment is to identify the level at which a student is. For this, it is important to first be clear about what a student is expected to have learnt in a particular grade. At the school level, especially at earlier levels where children learn to read and write and to do basic maths, assessment helps to determine how much they have actually absorbed from what they're being taught. This is the principle idea behind assessment at the school level, which led to the Teach at the Right Level educational intervention developed by Pratham, an organisation in India. The main idea of this intervention—later scaled to policy by state governments in India to reach 33 million children—was to place children in groups according to their achievement level (not by age) and then to provide remedial teaching so that those who'd fallen behind could receive the support they needed to catch up to grade level.

In our university admission tests or civil service exams, have we ever researched the questions we set in terms of whether they can help determine who will get a seat in our classrooms or who will become our civil servants? How we assess these candidates comes down to what we want from them. Do we want them to be free thinkers; have the ability to be critical, to be creative, to be ethical?

To identify the grade level a child is at, they need to be assessed properly. This is why my main concern about the assessment system changing with the new reform—"no more exams"—is that I am not sure that the new methods will allow us to properly identify children's grade levels. If the goal is to decrease the pressure on students, simplifying the curriculum seems like a good first step. Was it so necessary to suddenly eliminate exams? How can we reliably test whether a child can do, for example, a subtraction in the new system?

It is not a binary matter, really. It's not that we can either have exams or we cannot. To decrease pressure on students, changing the format of questions in exams could have played a strong enough role. For example, instead of asking a student to write a particular poem by Jibanananda Das, we could ask them to write what they felt after reading a poem. The former only tests students' memorisation skills, while the latter would test how well a student understood the poem and how well they could articulate their thoughts on it.

Undeniably, the type of assessment we use depends on what we expect students to know. And this is also the reason why assessment cannot be the same across school, college and university. Open-book exams, for instance, are more suited for the university level, not for school. At school, students need to learn some basic things—hence, we test them on those. At the university level, if the goal is for a student to be able to think critically, then the way we frame exam questions matters significantly.

In our university admission tests or civil service exams, have we ever researched the questions we set in terms of whether they can help determine who will get a seat in our classrooms or who will become our civil servants? How we assess these candidates comes down to what we want from them. Do we want them to be free thinkers; have the ability to be critical, to be creative, to be ethical? The Malaysian civil service exams include questions to test candidates' ethics by presenting scenarios to see how they would solve a problem—whether they would take a bribe or not, for example.

I welcome the effort to move away from memorisation-based rote learning. But even so, I am sceptical about at what cost this will be achieved. There are some aspects of an education that will always require memorisation, such as learning the alphabet or when training to be a doctor. The task is to filter out rote learning unless it is strictly needed, and to thereby question the presence of memorisation where it is not needed.

Education systems around the world, the best of them, research their assessment methods and constantly update them to meet the current criteria of what is expected of students. Notwithstanding matters of whether the rest of the education system is ready for a substantial shift in assessment, the question for the Bangladesh education system is: what is the goal and how are we sure that such a change will achieve it? Without a clear answer to this question, it seems unfair to launch something new and let our children be experimented on. Experimentation should be ex-ante for children before a big reform is introduced, not ex-post on children.

Rubaiya Murshed is a PhD researcher at the Faculty of Education, University of Cambridge. She is also a lecturer (on study leave) at the Department of Economics, University of Dhaka.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments